Gérard FOELLNER 1942 –

A good old companion …

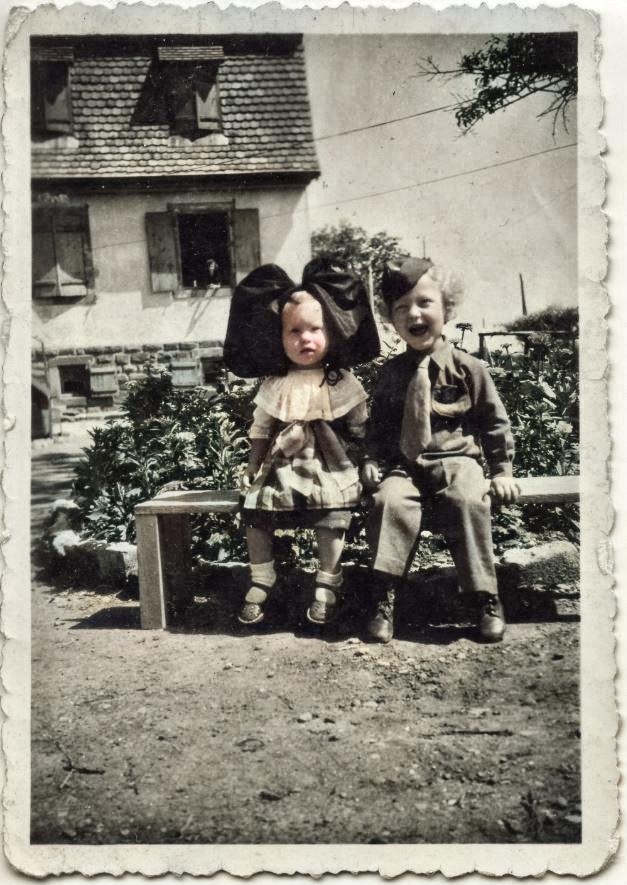

In 1945 Gérard Foellner, born on September 29, 1942, was two-and-a-half years old and lived on route d’Ingersheim, in Colmar (68).

Too young to remember the Liberation, he was nevertheless able to keep a material souvenir of the period: a small military uniform sewn by his aunt.

75 years later, he decided to donate it to the Musée Mémorial des Combats de la Poche de Colmar, thus contributing to the important task of remembrance and transmission.

On the day of the Liberation of Colmar on February 4, 1945, Gérard attended the parade of French and American troops in the company of his mother and aunt.

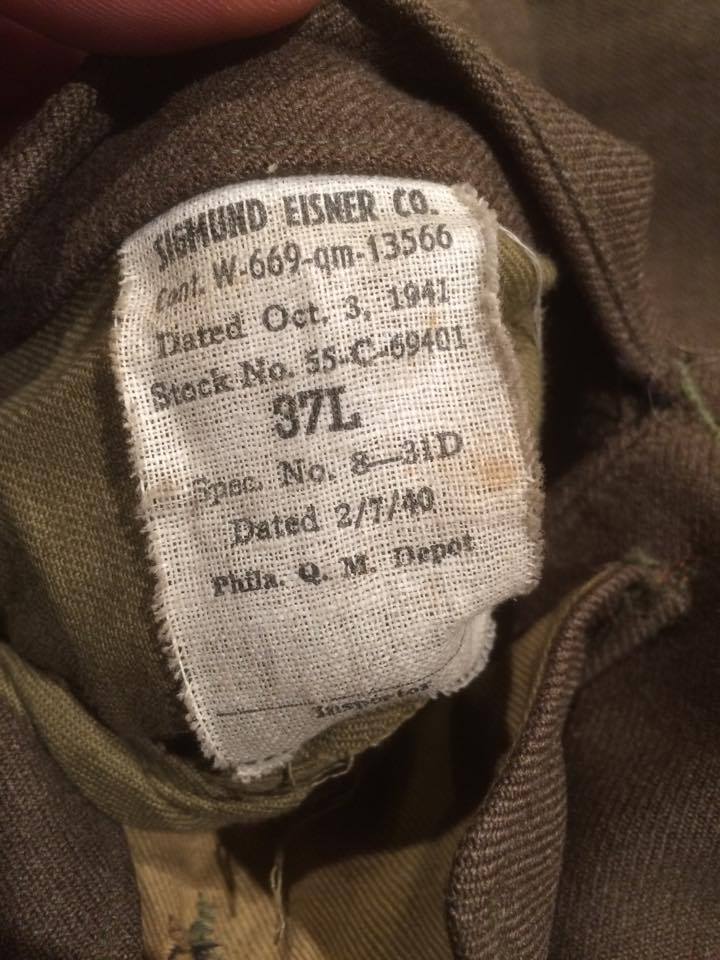

“I’d been taught to salute for the occasion,” he recalls. The little boy was dressed in his uniform, made for the occasion from the jacket of an American soldier.

As he performs his military salute, a French soldier steps out of line and hangs one of his medals on his suit.

An amusing episode that captures the jubilation of the Liberation festivities. “And look, I wasn’t just anyone,” he laughs, pointing to his commander’s stripes.

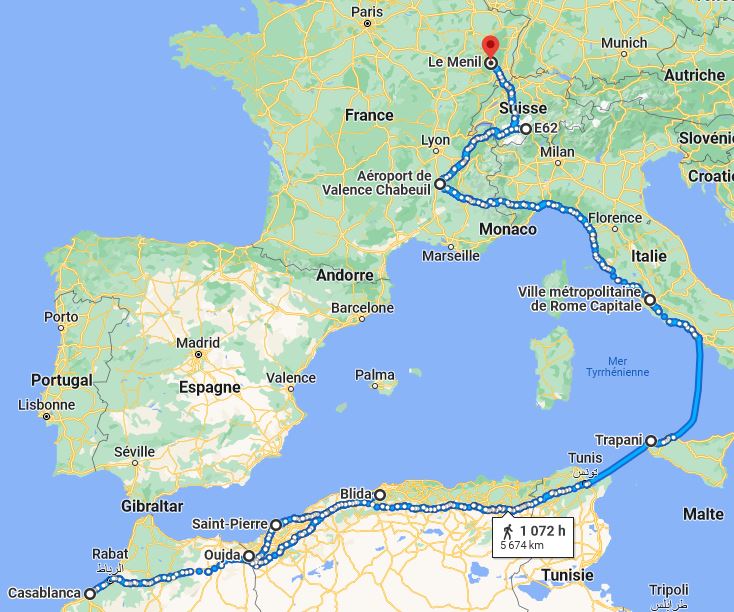

NB: Georges Foellner, his father, born in 1920 in Colmar, was forced into compulsory labor by the Nazis for three months in October 1942. He was subsequently drafted into the Wehrmacht and ended up in Nichlausburg, near Vienna (Austria). Sent to the Russian front, he joined Presnitov, near the Polish border. Wounded by shrapnel in October 1943, hospitalized for several months and after a fortnight’s convalescence, he returned to Nichlausburg, then to Italy in January 1944, where he took part in the fierce fighting at Monte Casino. After taking prisoner with the Americans, Mr. Foellner voluntarily enlisted in the French First Army. He left Naples for Marseille, finally arriving in Strasbourg, where he was demobilized in May 1945.

Frédéric KIENER says “BEAULIEU” 1913 – 1994

Paul Louis Frédéric Kiener was born on January 12, 1913.

He came from an old family in Riquewihr (68), in the heart of the Alsace vineyards.

Enlisted in advance of call-up on October 18, 1933, the young man did his military service with the 27th Bataillon de Chasseurs Alpins (27th BCA).

While working as a technical assistant at Sandoz, he was mobilized in 1939 and assigned to the headquarters of the 1st Battalion of the 42nd Fortress Infantry Regiment (42ème RIF) at Marckolsheim (67) on the Rhine.

Until the German attack, he served as officer in charge of poison gas. Caught up in the turmoil of June 1940, the officer narrowly escaped capture. He then wandered the roads of Alsace with his staff.

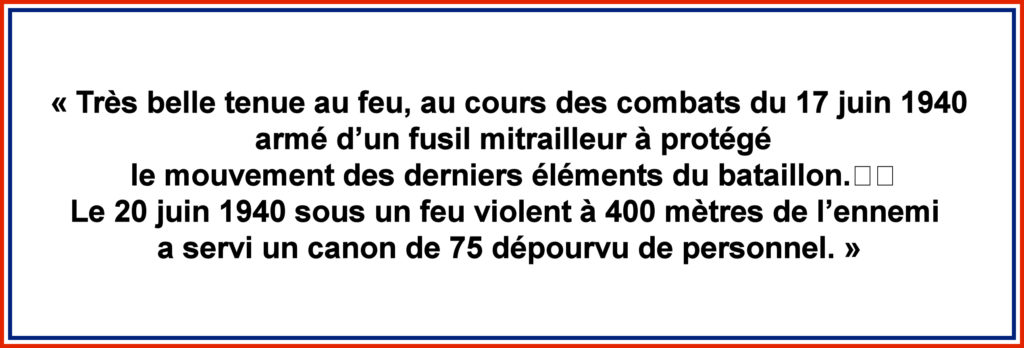

When they circled the village of Elsenheim (67) in the fog, they were spotted by enemy forces, and owed their salvation only to the decisiveness of Second-Lieutenant Kiener, who covered his corps leader’s retreat with an FM 24/29 machine-gun, and even managed to withdraw unharmed. His perfect understanding of German enabled him to understand all the orders given by the enemy in front of him and to anticipate them. Second-Lieutenant Kiener withdrew with disparate units of the French army and was assigned to “La Défense des Cols des Vosges”. During an attack, he single-handedly manned a 75mm cannon and managed to delay the enemy.

His first citation in the Regimental Order bears witness to this:

Taken prisoner, he was taken by train to Pomerania near Neu-stettin (Poland).

A first return to Alsace…

After the Franco-German armistice, Alsace and Lorraine were annexed to the 3rd Reich, and their inhabitants were considered de facto German citizens.

Alsatian prisoners were released at the request of the German authorities.

Lieutenant Kiener benefited from this curious “grace” and returned home on November 27, 1940!

No sooner had he returned home than he was summoned by the German administration in Colmar, where the occupying forces studied his record of service and offered him command of the S.A. Nazi Party in Ribeauvillé (68)… His negative response sounded like a condemnation for him and his family (his eldest daughter was born on January 31, 1941). From then on, time was running out for him, and he decided to reach the free zone via Switzerland.

North Africa…

His journey took him to North Africa, where he was posted to the 6th Régiment de Tirailleurs Marocains in Casablanca. Promoted to lieutenant, he took charge of the headquarters support group, comprising 4 x 81 mm mortars and 4 x 37 mm mountain guns.

In 1942, he was approached by the North African counter-espionage services. His perfect command of German made him indispensable.

In this capacity, he was one of “those of November 8, 1942” who enabled the Allied landings in North Africa.

His intervention with General Martin, who then had 5,000 well-equipped men ready to fight, was decisive….these French troops were left holding the bag.

After the liberation of North Africa, Lieutenant Kiener was posted on 12/1/1942 to the 8th Moroccan Rifle Regiment (8ème RTM), where he had time to familiarize himself with the brand-new American weaponry… he was an “unconditional” fan of the 81mm mortar, which he particularly liked.

From the 1er Bataillon de Chasseurs Parachutistes (1er BCP) to the 1er Régiment de Chasseurs Parachutistes (1er RCP)…

He joined the 1st BCP in Fez, Morocco, on May 1, 1943, where he took the alias “Beaulieu” to protect his family back in France from reprisals, including deportation (Alsatian soldiers fighting with the French army were considered traitors by the Nazis).

On June 3, 1943, he was awarded parachute brevet n°1130, and took command of the 81mm mortar platoon in the 3rd company of the new regiment (the 1er BCP became the 1er RCP on June 1, 1943).

In Italy…

Lieutenant Kiener followed the regiment to Sicily and then Italy, where his men learned to appreciate him and confide in him like sons. He was at their side during the Vosges campaign in October 1944.

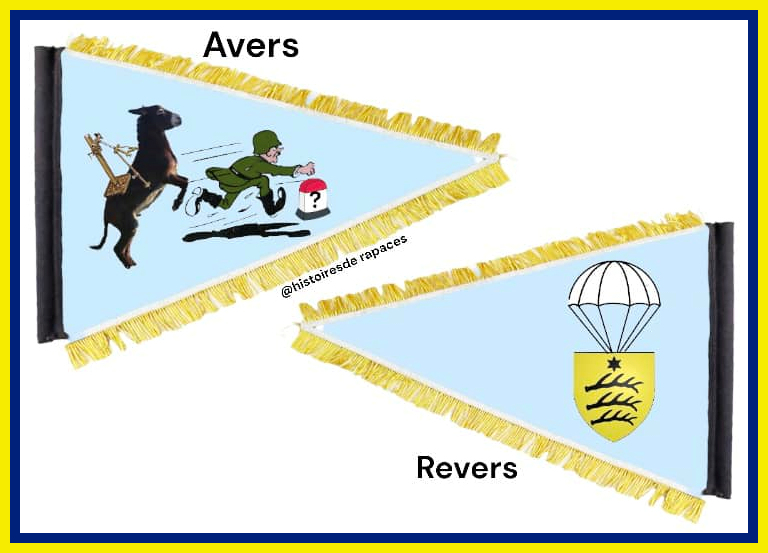

“It was in PACHECCO that Sicilian women embroidered my Combat pennant. Sky-blue silk embroidered with multicolored silk. On one side, it depicts a donkey standing on its hind legs, loaded with a heavy mortar and chasing a fleeing German. On the right-hand side of the road, a milestone bearing a red question mark. On the other side, a parachute and the coat of arms of the town of RIQUEWIR in the Haut Rhin department.

(three deer antlers surmounted by a star).

Memories of Lieutenant KIENER dit BEAULIEU of the 3rd Company

The Vosges campaign from October 2 to 22, 1944…

On October 6, with his best team, he destroys a German cannon that was threatening the regiment’s withdrawal to the village of Ménil(88).

The third shot from his gun landed on the ammunition store, destroying the artillery piece.

On October 8, having been particularly well informed by a German prisoner, he destroyed an enemy cannon with the first shot of his mortar fire during the attack on Ramonchamp(88).

He was cited in the regimental order:

On October 16, he accompanied his men to the peak of the assault on the Col du Menil. At the gateway to Alsace, the regiment was ordered to withdraw, and it was with a heavy heart that he buried his ammunition.

The Vosges campaign left him weakened and ill, yet as he writes:

“I felt that the battle for the liberation of Alsace was approaching, and for nothing in the world would I have agreed not to take part after three years away from my family and my native Riquewihr”.

The Alsace campaign…

The lieutenant got back on his feet and finally returned to Alsace in early December 1944.

On December 14, Lieutenant Kiener dit “Beaulieu” was wounded twice (“in both thighs) in 5 minutes in the Mayholz woods (67).

Shrapnel passed very close to the femoral artery, and despite shock treatment with penicillin, the wound became infected. He had to be operated on.

For this action, he was awarded a third citation: Mention in the Division Order:

“Magnificent officer, full of courage and composure. Leader of a mortar platoon, always knew how to get the maximum performance from his men. Was wounded on 14/12/1944, in the Mayholz while advancing with his unit under heavy artillery bombardment”.

He spent Christmas 1944 convalescing in Riquewihr, which had been liberated by American troops on December 5, 1944. There he found his family safe and sound (unfortunately, his father had died of illness during his long absence).

His groin injury was not well placed for further parachute jumping, so he turned to the intelligence services (BCRA) of the 1st Army, where he became a training officer for French agents until the end of the war.

Returning to civilian life in Riquewihr, he resumed his pre-war life and became an area manager at Sandoz and a winegrower. He had two daughters and 2 sons.

He died on April 20, 1994 in Saverne (67).

His decorations :

Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur,

Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with 3 commendations.

Medal of Liberated France.

Editor and pennant design: Guillaume Morelli – sources: 1er RCP documentary collection and Lieutenant Kiener’s memoirs.

We recommend the page created by Guillaume, a great specialist in the 1st RCP: “Histoires de Rapaces”.

Fernand GROSS 1922 –

Born on November 29, 1922 in Strasbourg (67), he was the eldest of 6 brothers and sisters.

Until the age of 6/7 and his entry into elementary school, he was raised by his godmother, who lived in the Palatinate in Germany.

Back in France, he entered the “Sœurs de la Providence” school in Strasbourg.

He joined the Cathedral choir school and the Manécanterie (singing lessons and choir).

A gifted child, he went straight from 8th grade (CM1) to 6th grade (did not attend CM2).

He then went on to study business at the Collège épiscopal Saint-Etienne until the 4th grade.

Throughout his youth, he was a member of the choir, first as a tenor, then as a soloist, and a scout (Cub Scout team leader, then patrol leader and finally scout patrol leader).

Stricken by meningitis, which somewhat disrupted his schooling, he easily made up for his “backwardness” and successfully obtained his commercial baccalaureate at the Ecole de Commerce in Strasbourg.

In his own words, “he inherited his mother’s sensitivity and singing ability, and his father’s energy and willpower…hence a leader’s soul”.

In 1939, at the age of 17, when war was declared, he and his family were evacuated to Montpon-sur-l’Isle in the Dordogne (374,000 Alsatians from 181 communes along the Rhine and the German border were evacuated to the south-western departments of France from September 1, 1939).

Fernand Gross’s family settled on a farm in the countryside, trading in pigs.

Fernand sees an advertisement and finds work at “la tannerie bordelaise et de la Gironde réunies”, where he quickly proves his professionalism. When the assistant manager left, he was offered the job.

In 1941, the family decided to return to Alsace (like most Alsatian and Moselle expatriates in 1940-41), and when he came to visit them, he was unable to return to the free zone (Alsatians being considered ethnic Germans had to remain in annexed Alsace).

His sister Alice, like all girls of her age (born in 1927), had to do a year’s compulsory civilian service as an apprentice cook in a rectory in Germany; she was only 14.

Like most young Alsatians of his age, he was drafted in October 1941, but in court, before the draft commission, he refused to sign, like 8 other Alsatians that day. Nevertheless, he had to go to the compulsory labor service with military preparation (Arbeitdienst) at Monbauer near Koblentz in Germany under the registration number K6252 until March 1942. There are 4 Alsatians and 16 Germans per barracks, with the aim of indoctrinating them more easily. Fernand Gross doesn’t let himself be influenced, and even has the courage to explain to them that they won’t win the war.

Meanwhile, in Strasbourg, 10 of his friends were shot by the Nazis for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets; repression became increasingly harsh, with many executions or deportations.

Living conditions and military training during Arbeitsdienst are very difficult. Fernand contracted double pleurisy and a kidney infection. A Bavarian non-commissioned officer “saved his life” by admitting him to the Sacré Coeur hospital in Dernbach at the beginning of December, where he received better care and was much loved by the medical staff. Back on his feet, he had to return to training camp.

A Prussian colonel who had discovered his anti-German “rebellion” doused him with a bucket of water as he was getting out of the showers and getting dressed for leave. He suffered another bout of pleurisy and was allowed to stay in Strasbourg for treatment, which enabled him to be released from his military obligations earlier than expected, and to benefit from a postponement of his enlistment. To speed up his recovery, he decided to take up swimming (in moderation).

Once cured, he enrolled as a student at the fine arts school in Strasbourg, where he won first prize, but the pro-German jury decided to award first place to a native German.

But the war caught up with him, and on August 25, 1942, Gauleiter Wagner decreed the forced incorporation of Alsatians into the German army.

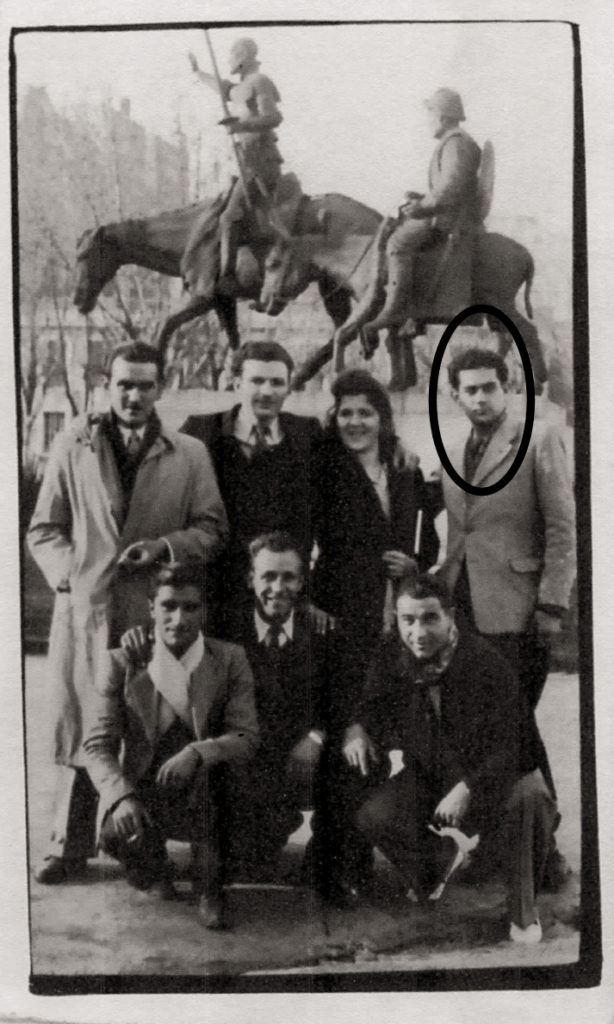

In October 1942, he received a mission order with a roadmap asking him to join a German parachute unit in Eger, Czechoslovakia. Before the train was due to depart, he got out on the opposite side with his best friend Ferdinand and climbed into another, knowing that their absence would not be noticed for 3 days. From then on, he had only one objective: to join the Free French Forces in North Africa!

He wrote a letter to his parents and godfather informing them of his intention to “desert”, and to protect them, falsely indicating his sympathy for the Germans in order to clear his name and avoid reprisals from the German authorities. Ferdinand didn’t… his parents were arrested and deported (they were lucky enough to return).

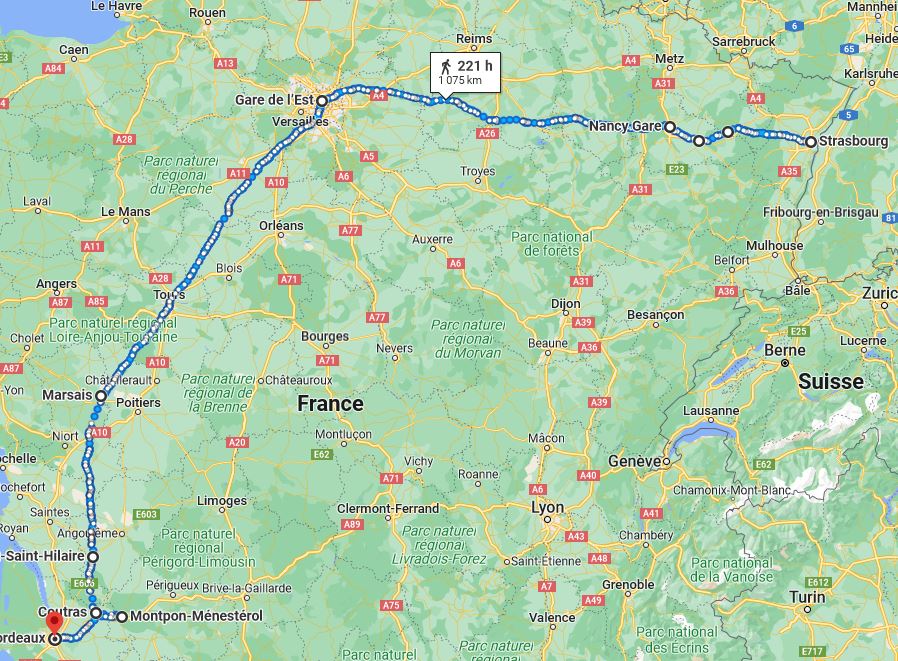

With Ferdinand, they travel by train to Nouvel-Avricourt (on the border between Alsace and Lorraine), where they meet a smuggler (via his aunt Mélanie and acquaintances). To be picked up by the smuggler, they have to whistle a predefined tune (“La victoire en chantant”) in front of the station. As the train pulled into the station, they spotted German soldiers on the platform carrying out checks: they were wanted! They quickly climbed out of the carriage they had just boarded through the doors opposite the platform and hid in the woods nearby. Sidecars and soldiers with dogs drive along the track and through the woods, but fortunately they are not discovered.

At nightfall, they return to the station to find the ferryman, but as they cross the many railroad tracks of the marshalling yard, they get their feet caught in wires on which pots and pans are hung (placed by the Germans), the noise of which alerts the German sentries and their dogs. Fernand and Ferdinand have just enough time to tear off 2 planks along a fence and put them back before the Germans and their dogs pass them by without seeing them… Fernand’s guardian angel is watching over them again (as he will often say).

Finally he finds their smuggler, who takes them to his house 2 kilometers away, where he had prepared the stamps (which were hidden in his clock) to make them their first false papers. They spent the next night in a hotel indicated by the smuggler, keeping the bedroom window open in case the Germans came.

The next day, they took the train to Lunéville, where they stayed for two weeks with an uncle who confirmed that they were wanted by the Nazis. They went to Nancy to pick up new false papers from a gendarme friend, Mr. Henner (who was later shot).

They travel to Paris, then to a convent in Marsais, near Tours, where one of their aunts, “Sister Claire”, lives, then to a second convent in Barbezieux, where they stay with another sister in the family and/or with an uncle, whom they help with farm work for about eight days. They set off again by coach to Coutras (33), then by train to Montpon-sur-l’Isle in the Dordogne, where they stayed with the Gauchoux family. The former manager of the tannery, Monsieur Goux, gave him the equivalent of 3 to 4 months’ salary to enable them to escape to Spain.

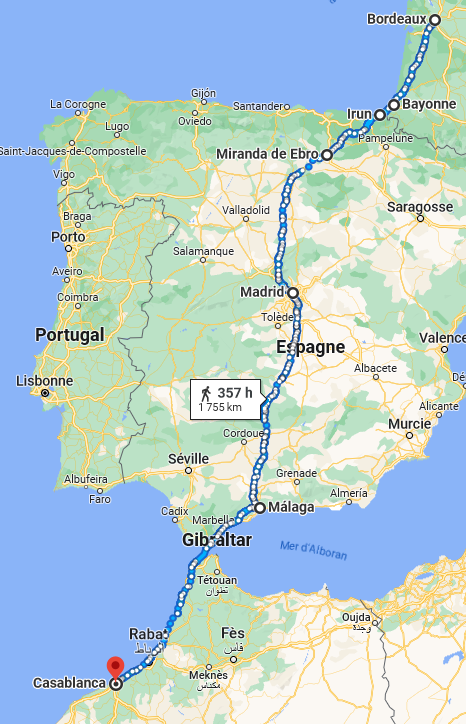

The rest of the journey was made by bus. As the Germans were checking the papers of all passengers, Fernand took the initiative and tried his luck by presenting his papers to the German inspector, who “saw nothing but fire”. They arrive in Bordeaux and are taken care of by the Red Cross, before heading for Bayonne, where they join a smuggler and his group (2 airmen and a woman) to walk to the Spanish border.

When Fernand shakes hands with the smuggler for the first time, his instinct (“his guardian angel”) makes him suspicious that he’s not being very honest.

Fernand immediately threatens him: “…if you don’t come back alone, know that I have a gun and I’ll shoot you first!

The smuggler returns very quickly, unchanged and unaccompanied, but with bottles of champagne…Fernand refuses to drink it, as he doesn’t trust him. To cross the border, the ferryman shows them the first bridge to cross, before abandoning them to their fate. Arriving at this bridge, Fernand again has a strange feeling (today he’s convinced that it’s his guardian angel who has protected him), and decides to cross at the next one, feeling the same way and sensing a trap…they then cross via the third bridge they find, where Fernand thinks there’s no danger. As they crossed, sirens wailed and searchlights came on at the first 2 bridges: they were expected, Fernand had not been mistaken, and thanks to him the group arrived safely in Spain. The date is December 2, 1943.

On arrival in Irun, Spanish customs officials check their papers (and confiscate all their belongings) and consider them deserters, given Fernand and Ferdinand’s age (21 = military obligations). They are transferred to “Villa del Norte” and taken prisoner. There they met the Red Cross and the Germans, who fortunately did not realize that they were Alsatians. They were given 20 pesetas a day for their daily needs. They save up whatever they can to play cards and buy wine to bribe the head guard, making it easier to plan their escape. They tell the Red Cross about their escape plan, and the Red Cross asks them to do nothing to avoid reprisals against the other prisoners. Seeing their determination, the Red Cross rushes in and organizes their release.

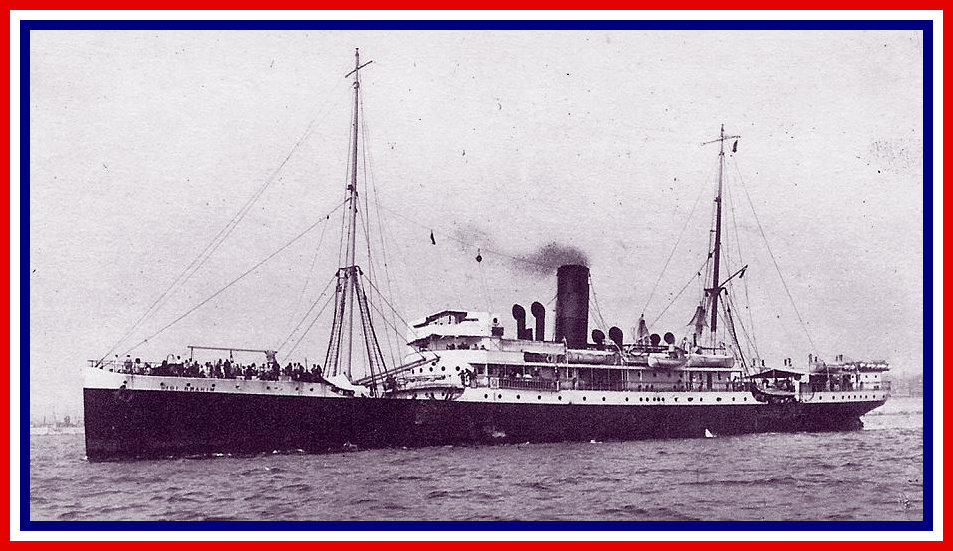

Liberated on January 5, 1944, they took the train to Madrid, then a bus to Malaga, where they boarded the “Sidi Brahim” with 1,500 other escapees from France (there was a second boat with 1,500 other escapees, the “Général Lépine”, which made the same crossing) to Casablanca in Morocco.

During the crossing, French and British destroyers intervened to counter German submarines.

As planned, when they arrived in Morocco (landing on January 6, 1944), they transmitted a message over the radio (BBC) to reassure their respective parents: “Zig et Puce have arrived safely”.

In North Africa, he receives his “real” false papers in the name of Fernand GOUX (the name of his former director, who had given him his approval during his last stay in the southwest).

Fernand joined the air force at parachute depot 209 in Blida, Algeria, where he was immediately included in the ranks of the 1st RCP.

His good friend Ferdinand was unable to follow him (heart problem during his medical check-up) and stayed behind as an interpreter.

After 3 months of intense training in Oudja, he left for Sicily with his new unit on March 31, 1944.

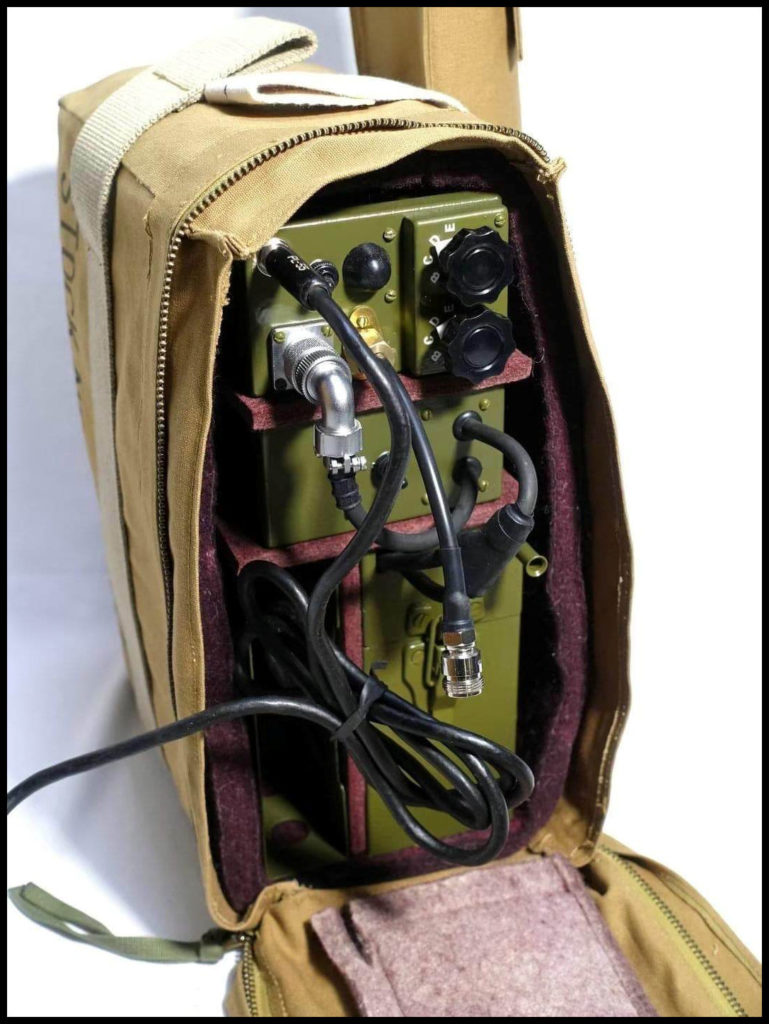

He obtained his parachute brevet number 1894 on May 5, 1944. A month later, Fernand was assigned to the 1st Company of the 1st RCP and joined the radio guidance platoon.

In Sicily, he was trained in the American pathfinder method, using top-secret PPN1 “Eureka” Transmitter receiver.

The radio guides are supervised by members of the OSS (future C.I.A.) to be trained in the use of these beacons at Camp Kurz. Parachute drops and exercises follow one another at a frenetic pace, to ensure that the radio guides are ready for any situation.

He joined the regiment in Rome at the beginning of July 1944.

Fernand then followed the regiment’s peregrinations, from the train journey back to Rome in July to its arrival in France on September 5, 1944, where it landed at the Valence-Chabeuil airfield in the Drôme region.

On September 15 1944, the 1st RCP regrouped in front of the Belfort Gap.

At the beginning of October, attached to the 1st French Armored Division, the regiment received its baptism of fire in the Vosges.

Fernand Gross tells us:

“Because of the fortifications built by the Germans around Belfort, we had to bypass the Vosges. Many attacks by German units took place in the winter of ’44, in the cold and snow, and were therefore very difficult: we had to sleep in a snow hole and hide under a white sheet during the day, so as not to be seen by the Germans. One day, as the shooting was getting closer, I warned the others to “get down on the ground” just before a shell burst in front of me, and everyone thought I was dead… I was only slightly wounded in the eye.

Later, still in the Vosges, Fernand recalls a second particularly astonishing episode:

“Walking through the forest, I feel an abnormally hard patch of ground under my foot; I stop moving and suspect I’ve stepped on a mine. I mechanically lift my head and see a deliberately broken tree branch in the air, a sign that a mine has been placed there by the Germans: I immediately remember the training I underwent at the Arbeitsdienst and the “habits” taught by the German instructors for marking a booby-trapped spot. Having also taken a mine-clearing course in Sicily, I’m very familiar with the different types of German mines. I shouted to the others, “Get away quickly, I’m on a mine”… and immediately made a desperate 3-meter leap towards the nearest tree, the mine exploded and miraculously I was unharmed.

Like many paratroopers, he was medically evacuated due to illness or frostbite during the Vosges campaign, then during the fighting in Alsace on January 6, 1945, due to weather conditions and fierce fighting.

The regiment left Alsace for Bourges to replenish its reserves and allow the men to recuperate… Fernand weighed only 46 kilos (he had 70 at the start).

His brother Marcel, also drafted into the German army on the Russian front and missing for some time, was also lucky enough to return home after the war.

Fernand was demobilized from the army on July 3, 1945, and helped his father in the family painting business. He then joined the Singer company, rising through the ranks to become manager of his sector.

He married Alice Daull in Schiltigheim on June 18, 1949, and the family circle grew to 6 children. To make up for Fernand’s frequent absences from work, the couple decided to open a haberdashery and clothing boutique (later 2 other stores).

They decided to settle in Gujan-Mestras, where Fernand built a small house on his own (patented) model, and left Strasbourg in 1987-1988 to finally enjoy a well-deserved retirement in the Arcachon basin. In 2009, they celebrated their golden anniversary together.

Alice Gross, his wife, died on November 5, 2018 at the age of 91.

On November 29, 2022 Fernand had the joy of celebrating his centenary surrounded by family and friends.

Fernand Gross is the holder of :

La médaille des évadés

La Croix du combattant volontaire avec barrette ” 39/45 “.

The Italian Campaign Commemorative Medal

The French commemorative medal for the 1939/45 war, with “liberation” and “voluntary service” bars.

Fernand Gross 1944 – 2023…

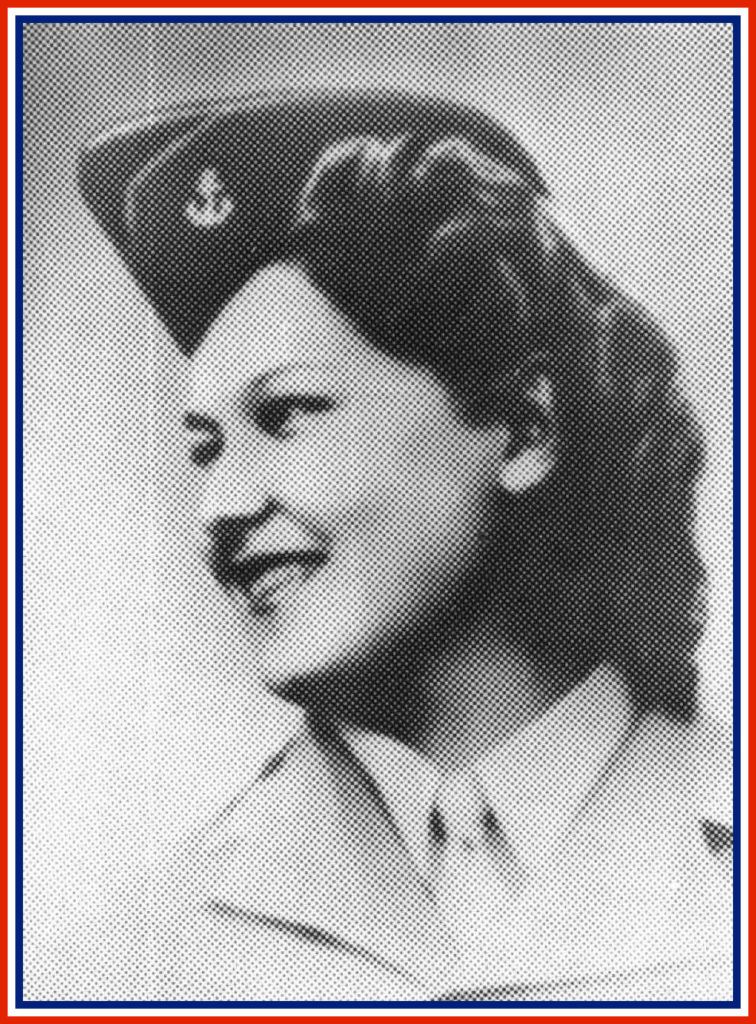

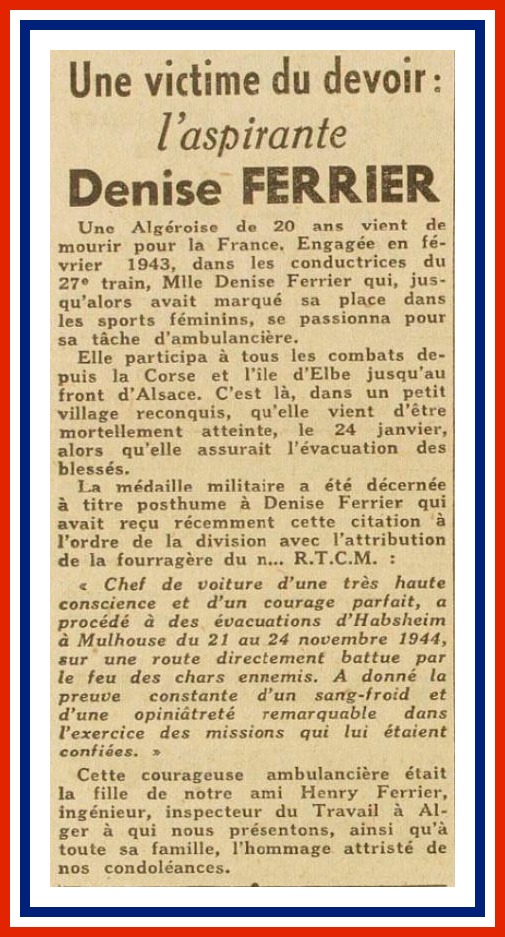

Denise FERRIER 1924 – 1945

Born in Arba on November 16, 1924, she spent her childhood in the Algiers region.

She was the youngest of 4 brothers and sisters. A good pupil, she prepared for her brevet élémentaire and considered taking the competitive entrance exam to the Ecole Normale, but the Vichy decrees reserving the teaching profession for those with a baccalaureate prevented her from pursuing the path she had set her sights on. She loved reading and physical exercise more than anything else, and was an accomplished sportswoman. From the age of 8, she belonged to women’s sports associations including Algéria-Sports… gymnastics, basketball, high jump…

In 1938, she took part in the Fête Fédérale Nationale in Dijon. That same year, she travelled with the French delegation to Prague for the Sokols festival.

It was during this period that she revealed her qualities: a sense of teamwork, enough authority to guide others, modesty to be one with the group without seeking to distinguish herself from it, and a natural tendency to help like a “big sister”. She chose a career as a physical education teacher in elementary school, at a time when war and the armistice had plunged France into turmoil…

She listened attentively to the BBC and, with her friends, drew Vs in charcoal and chalk, encouraging the weak to join the passive resistance.

On November 8, 1942, she had a front-row seat for the landing of American troops in North Africa.

In 1943, her friends enlisted in the French army, and thereafter women also had the opportunity to join, but mainly in “menial” tasks. For Denise, this was not enough, and after much insistence on the part of the military authorities, she was admitted in February 1943 to the driver’s corps of the 27th Train…she was 18 (her father would only ask her to complete her training as a physical education instructor to enable her to pursue her chosen career after the war).

At the beginning of 1943, a corps of female drivers was created in Algiers, attached to the Train des équipages under the command of Mme Gross, and trained by the 27th Train’s managers.

The first volunteers were mainly refugees from mainland France, women from Alsace and Lorraine, prisoners’ wives and later Algerian women. Other schools were set up in Marengo, Chéragas, Constantine and Oran.

They learn driving, mechanics, topography, countryside orientation and stretchering, as well as health training, enabling them to fulfil the role of driver and nurse at the same time.

The training program was intense (6 weeks) and the rules strict. Hundreds of women were trained and placed at the disposal of fighting units in groups of ten drivers under the direction of a team leader. The first women took part in the Tunisian campaign.

At the beginning of May 1943, Denise passed her driver’s exam and signed up for the duration of the war. She opted to drive ambulances in the French Expeditionary Corps. She will be part of a pick-up company in a Medical Battalion. She took part in an advanced training course for ambulance drivers. It was during this period that she began writing a series of 126 letters, the last of which was written just before her death.

“The steering wheel is on the left and the gears are shifted with the right hand…we drive for 8 kms each. It’s amazing…there are 6 of us in the car, 6 women on their own, singing at the top of their voices, the wind in their faces…the comrades are kind: we all help each other…”

Appointed driver and her comrade Claire her assistant-driver, they are assigned vehicle n°432930, which they christen “Marie-Elisabeth et Michèle. For the great adventure”.

The Medical Battalion had 3 pick-up companies, one of which was all-female. On July 15, 1943, she arrived in Sétif, where she carried out a series of exercises and missions.

In October, following an attack of malaria, she was hospitalized in Oran and had to leave the Bataillon médical n°3. She joined the Territorial Section, where she attended management school, graduating with the rank of midshipman. She obtained her “heavy goods vehicle” license and for 4 months was responsible for evacuating the wounded brought in by hospital ships and medical trains to hospitals in Maison-Carrée, Blida and Miliana.

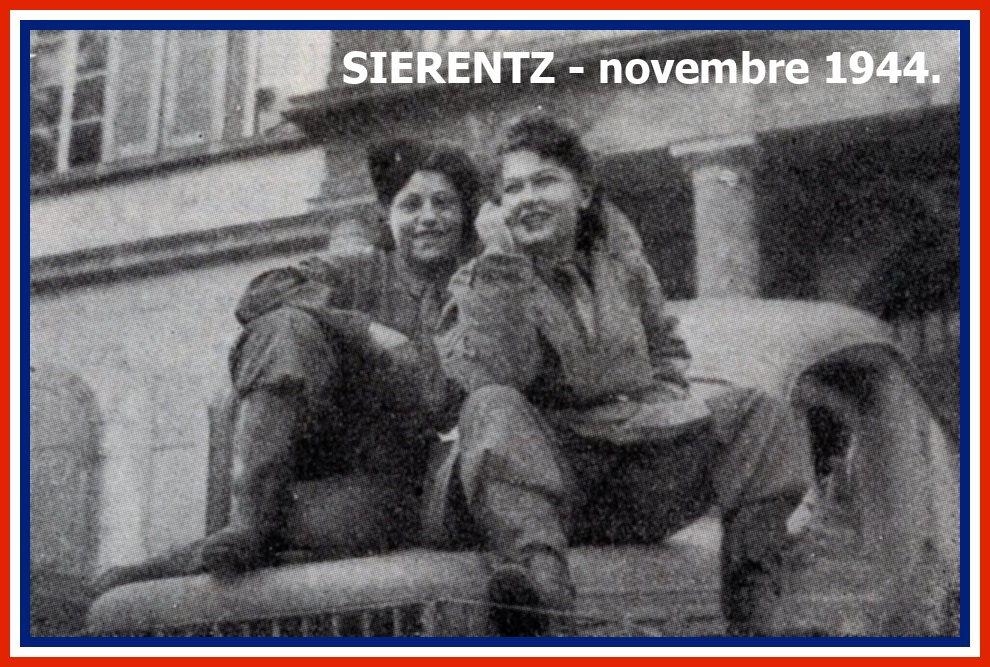

In March 1944, the 25th Medical Battalion was created, and she and her friend Paule Texeire volunteered to join it.

Departure was imminent, and she wrote to her parents: “The day I sign Marie, you’ll know I’ve arrived abroad. Corsica will be Mariette, France Marcelle, Elba Joséphine…”.

On May 5, 1944, Denise and her comrades were in Corsica. She had 7 girls under her command, discipline had hardened and she knew the responsibilities she had to shoulder. They practiced embarkation/disembarkation maneuvers, and changed cantonments several times.

On June 5, she learns of the fall of Rome and writes: “Today is a splendid day, for the Allied troops have entered Rome. It’s magnificent, wonderful! We can now think that the good and real work will not be long in coming.

Denise landed on the island of Elba on June 16, 1944, where by the time she arrived, the Bataillon de Choc and the Goumiers had already taken Marina de Campo. Her first mission saw her recover 2 tabors and a wounded non-commissioned officer, to be taken to the sorting and treatment company on a tortuous, narrow road with large shell holes.

As a result of his actions and courage, he was awarded his first commendation, to the 9th DIC:

“Ambulance driver of the 25th Medical Battalion who, during operations on the island of Elba, demonstrated ardor, enthusiasm and a courage that won the admiration of all combatants. On the morning of June 18, in the Speggia Grande area, in the midst of battle, pushed right up to the battle line to search for wounded. Accomplished this particularly perilous mission with perfect control, remarkable drive and absolute disregard for danger.

At the end of June, she returned to Corsica before the “big day”…on August 23, 1944, she and her comrades waited to embark near Ajaccio, where she wrote: “That’s all, my dear little parents. We are leaving happy and ready to make any sacrifice. Just think of this wonderful thing: Paris has been recaptured and victory is fast approaching.”

The “Chaufferettes”, as the ambulance drivers of the 25th Medical Battalion were known, disembarked at La Nardelle, between Saint-Tropez and Saint-Raphaël, and headed straight for Toulon. Throughout September, they carried out a series of day and night missions (no location is mentioned in their correspondence, as required by military orders in wartime). At the beginning of October, the weather turned cold and they slept in their medical vehicles.

Around October 15, his unit arrived in the Doubs region after camping out in the villages of the Isère region. They bravely continued their task under daily artillery bombardment.

On her 20th birthday, November 16 1944, she wrote: “There’s no question of rest for the time being (she had the possibility of going on leave for 6 days). It’s the attack, the real one, the one that requires men and ambulance drivers too. Here we are.” No time to celebrate this anniversary when so many little boys are dying so close to her and her comrades.

Montbéliard was liberated on November 17, followed by Belfort on the 20th and Mulhouse on the 21st.

Denise and her friend Paule Texeire were assigned on November 20 to the Régiment d’Infanterie Colonial du Maroc (RICM), known as “the reconnaissance regiment that goes everywhere first”.

. Denise takes great pride in this, and is delighted to be the first to witness the joy of the Alsatians who have been waiting 5 years for their liberators. From the 23rd onwards, the wounded were evacuated to Mulhouse.

In Habsheim, where shells were raining down, they had to move the first-aid post 3 times.

By the end of November, her unit had covered 500 km in 7 days, and each ambulance had transported around 30 wounded.

The snow began to fall and the cold became increasingly “biting”.

Before leaving the sector, the Colonel presents the RICM fourragère in the colors of the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre to Second-Lieutenant Mme Burgel, Midshipman Denise Ferrier and Driver Marie-Louise Mathieu.

All 3 will also be entitled to wear the Distinguished Service insignia awarded to the RICM. They can be proud of themselves and the work they’ve accomplished.

Between missions, Denise continues to write about her life at the front for her parents, whom she loves so much.

In December 1944, Denise Ferrier was cited in the Division Order for her conduct during the RICM battles, and awarded the Croix de Guerre.

Mentioned in the Division Order:

PC on December 21, 1944, Major General Pierre Magnan, commanding the 9th DIC, commended Aspirant Denise Ferrier of the 25th Medical Battalion to the order of the Division:

“Car chief of the highest conscientiousness and perfect courage. Carried out evacuations from Habsheim to Mulhouse from November 21 to 24, 1944, on a road directly battered by enemy tank fire. Gave constant proof of remarkable coolness and doggedness in carrying out the missions entrusted to it.

She remained in Mulhouse until December 14, when, as she set up camp, she saw her cousin Robert pass by on a tank: she was very happy to see him again. At the end of the month, she was again in the Altkirch sector, where fierce fighting had resumed and medical evacuations were in quick succession (shrapnel, mines, etc.); she wrote “… until the whole of Alsace is liberated, we won’t be able to rest!

At Christmas, she writes: “For all the children it’s Santa Claus Day, for the grown-ups it’s New Year’s Eve, the wonderful evening of dancing, fun and drinking. For those who fight, it’s the attack, the bullets, the holes where for hours we watch out for the enemy. For us, it’s the daily grind that goes on. Today’s gift from heaven is simply -12 degrees… and duty comes first!

Denise’s gift to her parents is a quote: “I send it to you with my heart, with my youth and my kisses.

Denise gets through the New Year in relative calm, apart from a shift on December 28 in Morschwiller.

She dreams of a leave to see her parents in Algiers.

On January 10, close to the front, we learn that a Colonel is coming to inspect his section and review the women drivers and their equipment. Denise writes, “All in all, he was smart and not too demanding”. It was on this occasion that the army photographers immortalized the moment with Denise and her teammate in front of their car.

From January 13 to 18, Denise was on permanent duty with the 3rd Battalion in Didenheim, evacuating soldiers and civilians.

In her last letter, we read: “Since this morning, we have all been consigned. Several cars have left to reinforce us. We’ve doubled the number of shifts. It smells of fighting. Tomorrow, January 20, we’ll be ready at 8am. And that’s it!”…” 4 furloughs every 10 days for the entire Medical Battalion (900 people in all). I don’t even dare calculate my turn. I just wait and see!

On January 21, Denise Ferrier’s section entered Pfastatt and took up residence on the 3rd floor of the civil hospital, where the entire Medical Battalion was housed.

Bitter fighting took place in the Richwiller commune from January 19 to January 24, 1945, in Siberian temperatures and heavy snow.

On the 23rd, under the command of section leader Captain Mazieux and team leader S/L Mohring, ambulance drivers Denise Ferrier, Marie-Rose Bajeux and Paule Texeire were sent to Richwiller to rescue the wounded from damaged houses. The enemy had left the village center.

Au bistro Bailly-Fassnacht du 99 Adolf Hitlerstrass, le Bataillon de choc y avait installé un poste de secours. De nombreux blessés y étaient acheminés et on racontait que là-bas, ils nettoyaient le sang à grand coup de sceau d’eau. A côté se trouvait l’ancienne forge du maréchal ferrant “Mouillée” qui servait de morgue provisoire (les cadavres y étaient entreposés entre un stock de sacs de farine).

Après une épuisante et éreintante journée, nos ambulancières trouvèrent un gîte à l’épicerie-tabac Bir, en face du poste de secours miraculeusement épargnée. La propriétaire des lieux possédait un piano et après le diner, près d’une amie qui s’était installée au piano, Denise commença à chanter à ses camarades « ALGER la blanche », chanson pleine de nostalgie sur son pays natal, que toutes avaient maintenant l’habitude de reprendre en chœur au moment du refrain…demain elles ne pourront jamais plus chanter cette chanson sans éclater en sanglots…

To her great joy, that same day she received a long, affectionate missive from her parents and a telegram from her father advising her to apply for a transfer to the Territoriale…but the young woman didn’t let herself be persuaded!

The tired girls did not prolong this impromptu musical evening. As they went to bed, they heard the distant thunder of artillery fire at the Meyerhof, the forerunner of the next day…

January 24, 1945, 6:30 a.m., the ambulance drivers are suddenly awakened: “The Battalion is on the move, get ready!”

Denise writes a quick note to her parents before going to perform the daily technical inspection of her vehicle.

The others gather their belongings, load equipment and stretchers, rev up the engines.

Paule Texeire has prepared the coffee, 2 comrades follow her, she asks Denise to come along; she gets out of her vehicle, raises the running board, everything is ready!

Suddenly, the whistle of a mortar shell followed by an enormous crash…. attracts the first-aid personnel…it’s 7 a.m., and Midshipwoman Denise Ferrier, who has received multiple commendations, has just been mortally wounded (a piece of shrapnel in her back struck her heart) in front of 99 Adolf Hitlerstrasse. Her sisters-in-arms rush to her aid, but it’s already too late….

The young woman, who had just turned 20 and was looking forward to her first leave, would never see her parents or her home in Hydra, high above Algiers, again.

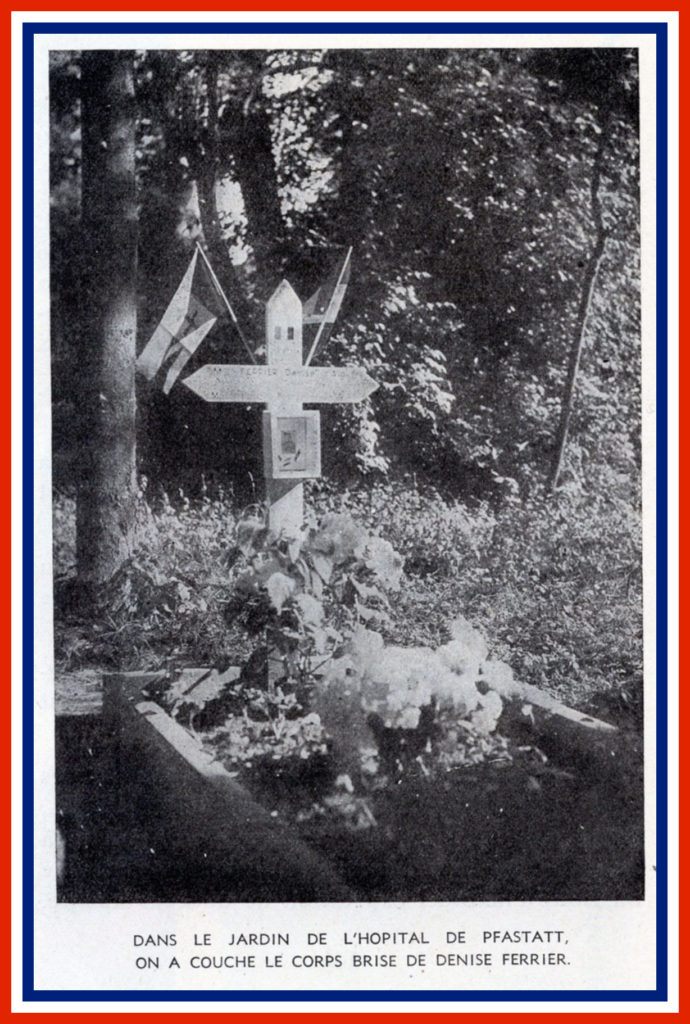

Her body was placed on a stretcher and transported (in turn) to Pfastatt hospital, where the following day she was provisionally buried in the gardens, in the presence of all the ambulance drivers: she was awarded the military medal and military honours were paid to her.

By decree of April 17, 1945, she was awarded the military medal and the croix de guerre avec palme.

Denise Ferrier’s final achievement was recognized by a citation in the Army Order, which read as follows:

“Ambulance driver of the 2nd collection company of the 25th Medical Battalion, who had already made a name for herself on the island of Elba through her composure. Since the start of the French campaign, she has volunteered for all forward missions, constantly giving of herself and evacuating many wounded. Participated with the RICM in the breakthrough on Mulhouse. Killed by a shell on January 24, 1945 in Richwiller, at 7 a.m., in front of a first-aid post of the Bataillon de Choc. A young Frenchwoman of the noblest ideals, imbued with the motto of her section, “Franchise et Vaillance”, she will remain for all those who knew and loved her a pure model of ardent patriotism and smiling heroism”.

Beyond Pfastatt, on the road to victory that the child of Algiers was not to complete, a sanitary car continued on its way, bearing on the front of its hood a now glorious name: “Conductrice Denise Ferrier”.

To Denise Ferrier,

To all the women who, in the Resistance or at the front, sacrificed their youth, and in some cases their lives, for the salvation of France.

Text based on Lucienne Jean-Darrouy’s 1946 book “Vie et mort de Denise Ferrier”, with the help of Jean-Marc Munch.

Source photos: “Vie et mort de Denise Ferrier” 1946 – Mr. Jean-Marc Munch – internet.

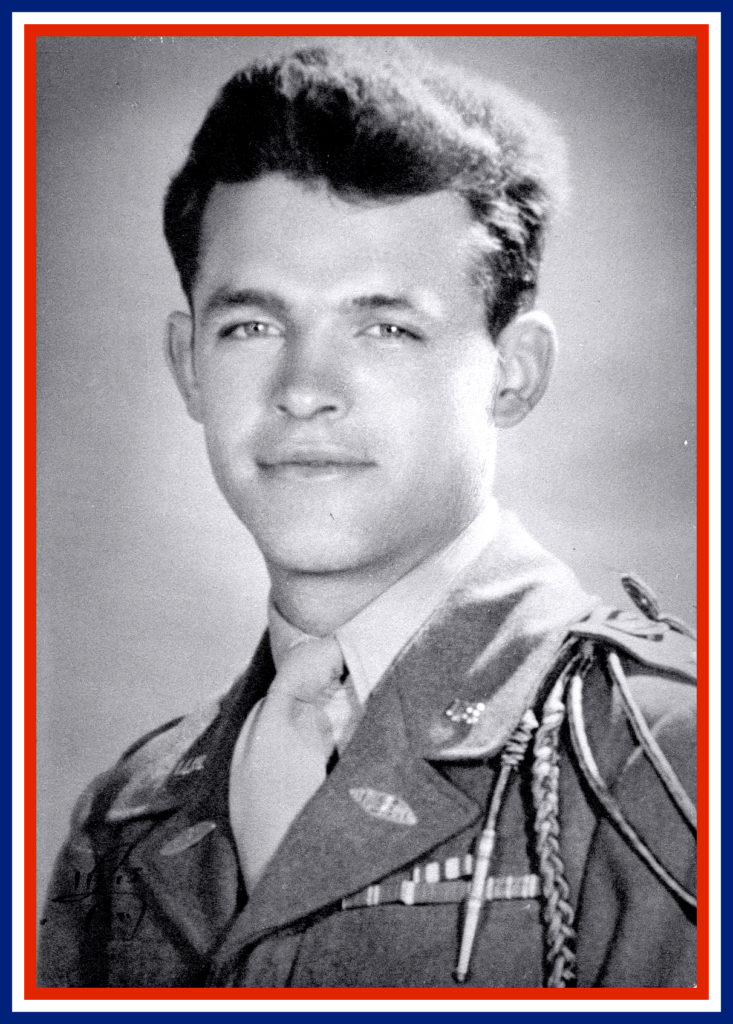

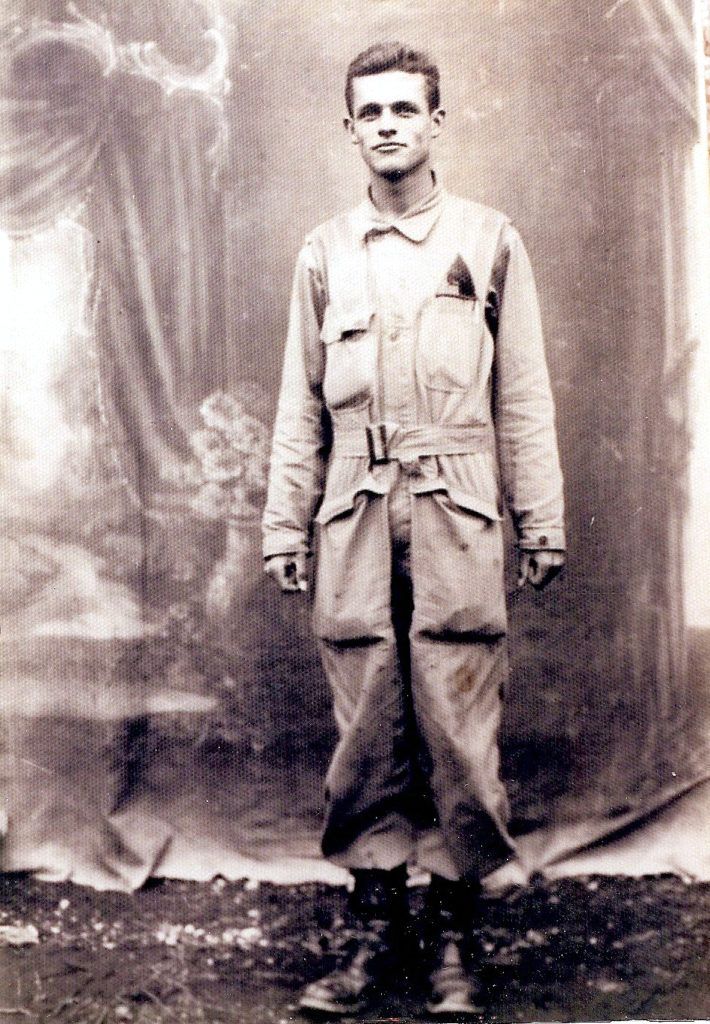

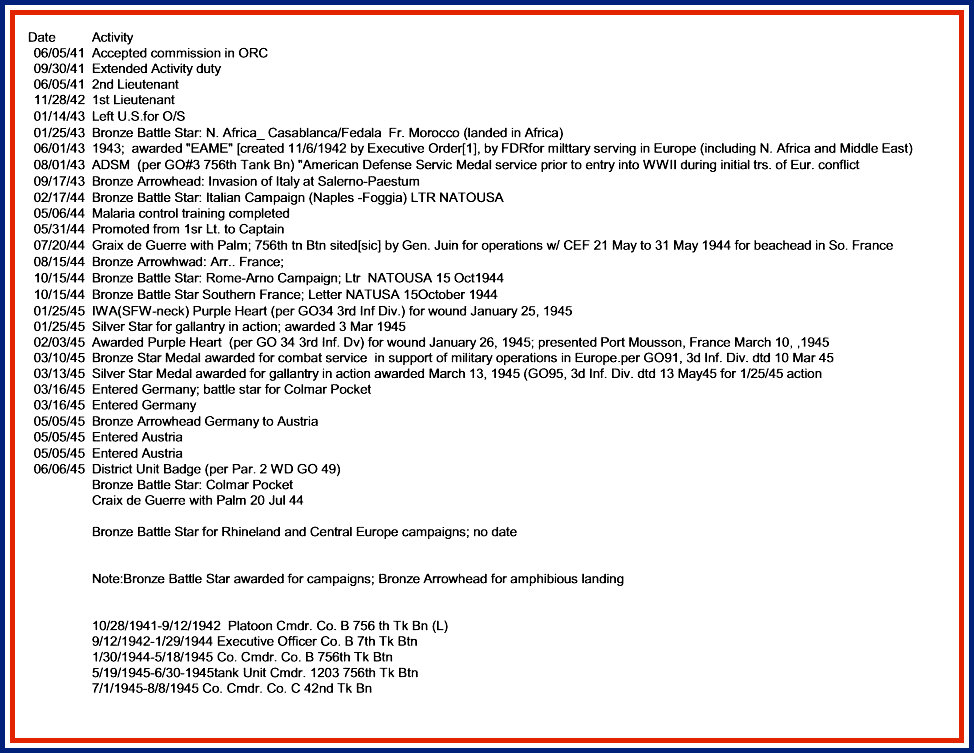

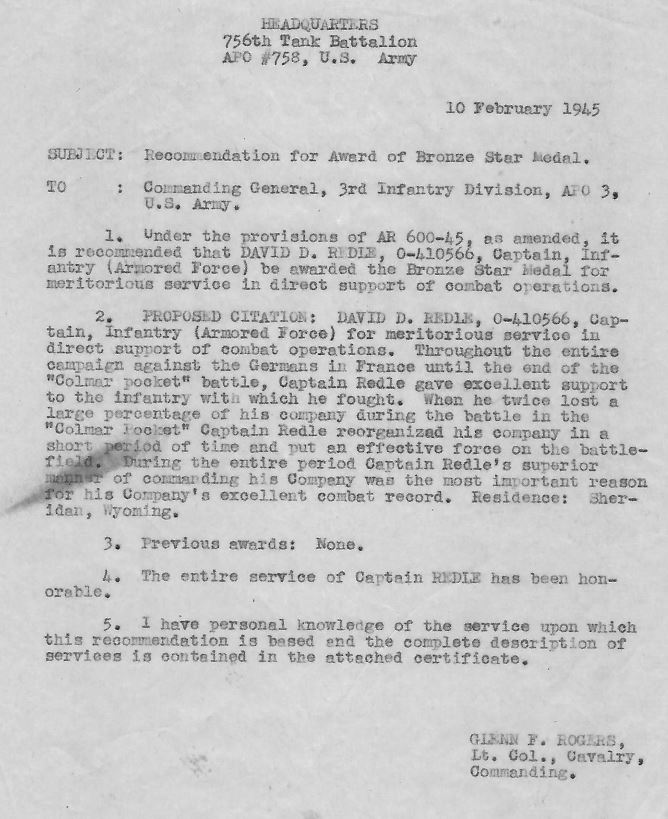

David Dillon REDLE 1918 – 2015

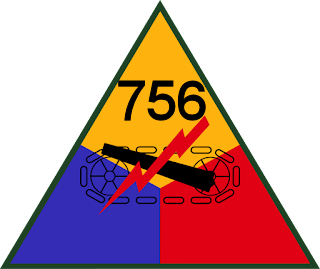

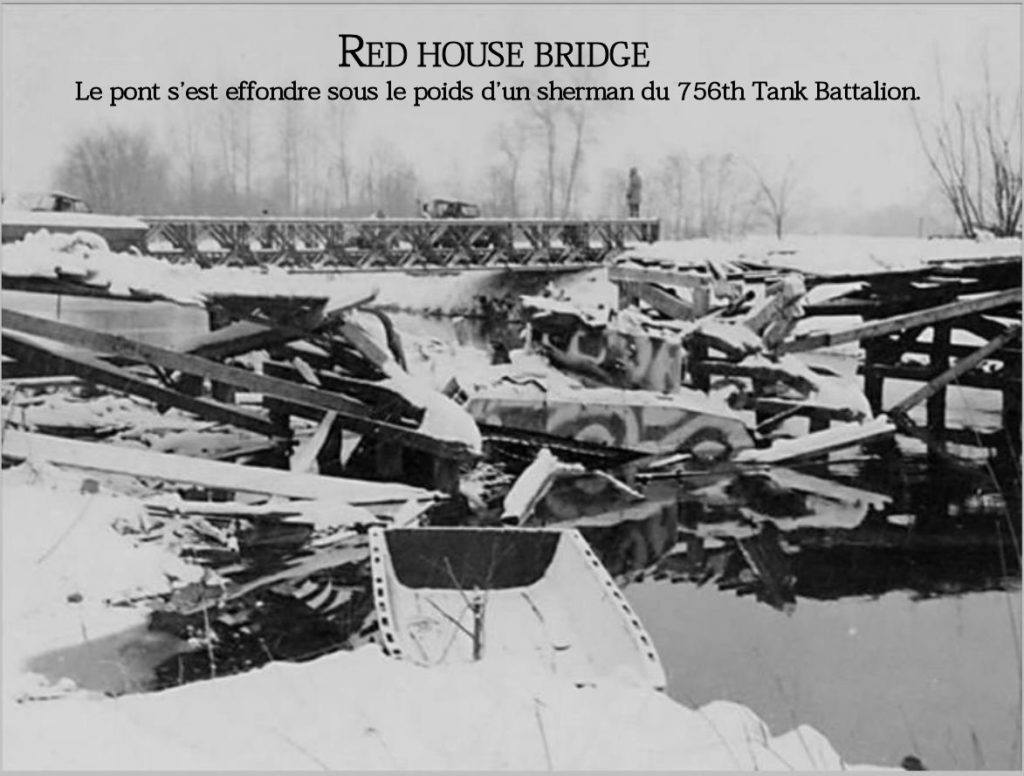

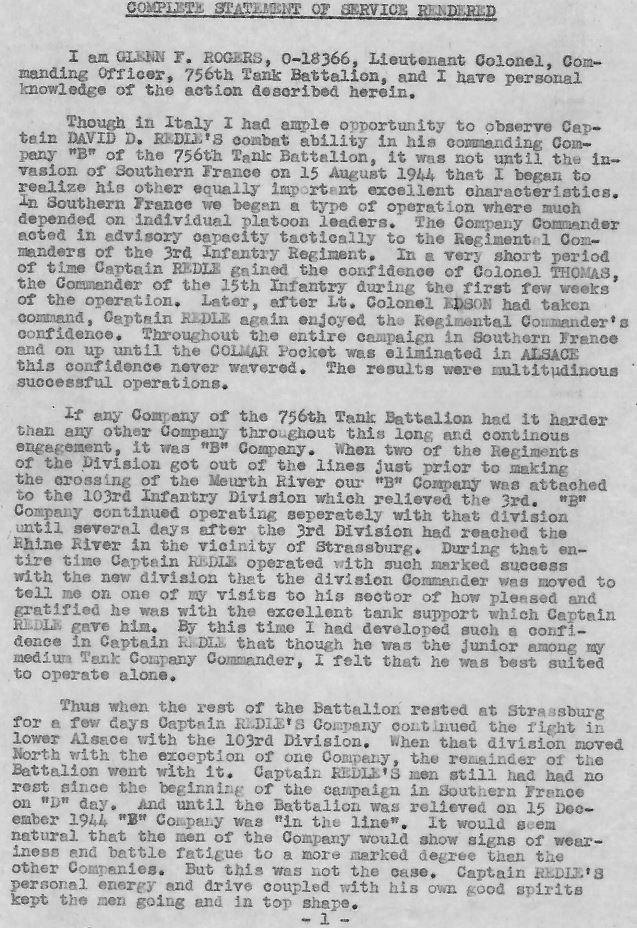

Captain David Dillon Redle commanding Company B of the 756th Tank Battalion, who fought with the 15th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd American Division during the fighting in the Colmar Pocket.

David Dillon Redle was born on July 17, 1918 in Sheridan, Wyoming, and joined the US Army in September 1941.

He will be part of every campaign with the 756th Tank Battalion : MAROC – SALERNE – NAPLES – MONTE CASSINO – ROME – PROVENCE – ALSACE – ALLEMAGNE.

During the fighting in Alsace, he was awarded the Bronze Star on 02/13/1945 (for his actions and good conduct “under fire” for over 3 months), the Silver Star (on 01/25/1945 for fighting in the Riedwihr sector) and the Purple Heart (mortar splinter to the neck in the Riedwihr-Holtzwihr sector).

After the war, David D. Redle held various positions with PPG Industries in Barberton, Ohio, retiring in 1983 at the age of 65. He and his wife, Elizabeth, raised eight children. He passed away on January 7, 2015 at the age of 97.

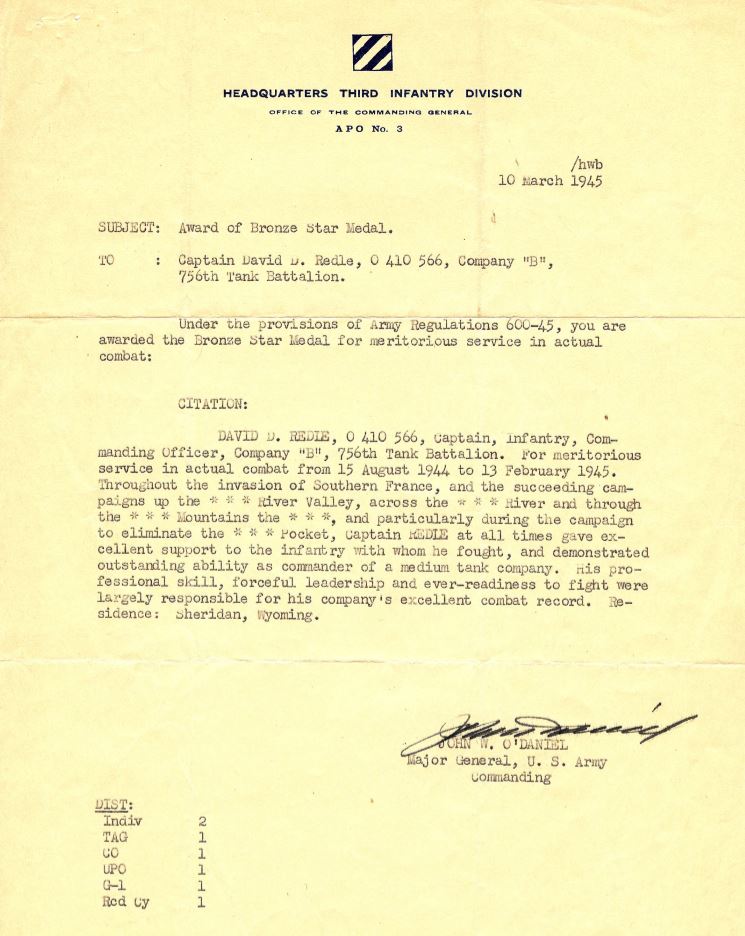

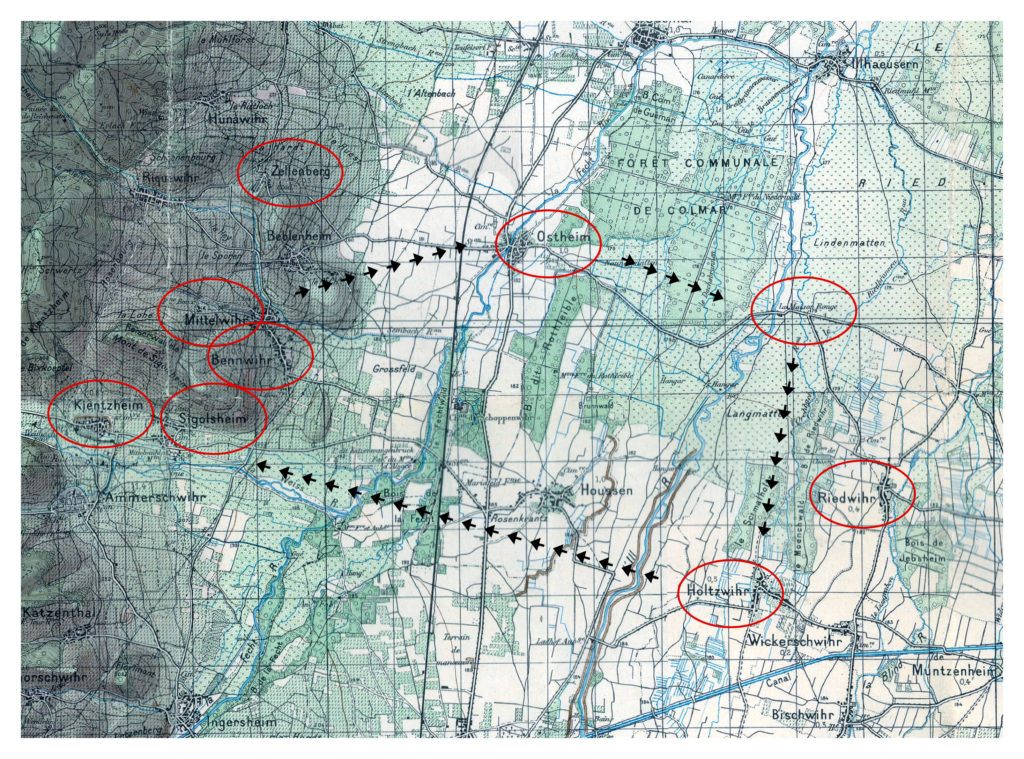

In December 2018 we followed in the footsteps of Captain D. Redle on a “memorial tour” with his son David and granddaughter Kathleen.

We went to SIGOLSHEIM – BENNWIHR – MITTELWIHR – OSTHEIM – MAISON ROUGE – HOLTZWIHR, places that Captain Redle had mentioned in his memoirs.

These few lines are dedicated to the memory of Captain David D. Redle, and to all our American and French liberators who fought for our freedom.

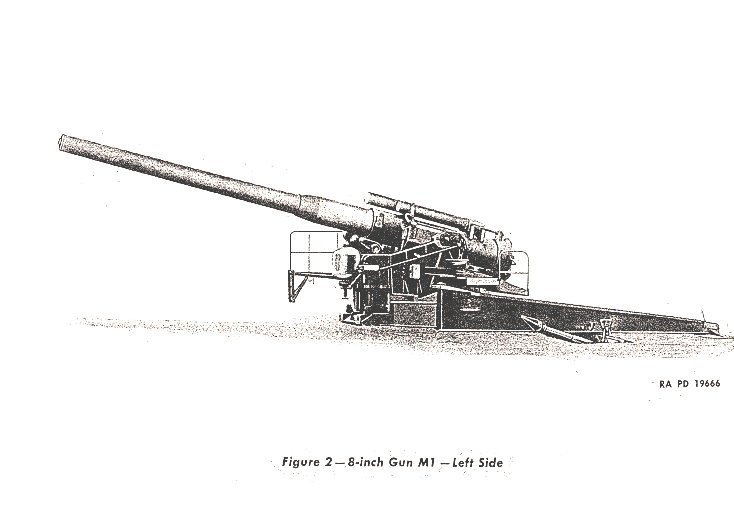

Container for a propellant charge for an American « 8-INCH GUN M1 US ».

The propellant charge (35-kilogram M9) contained in this container made it possible to fire a 108-kilogram shell (US M103 HE SHELL) at a maximum distance of 32 kilometers with the 203mm 8-INCH GUN M1 heavy artillery piece.

Designed at the same time as the 240mm M1 howitzer, the 8-inch GUN has many features in common with the 240 (same breech, same carriage, same mounts and gun tractors). Between 1942 and 1945, 139 were built (315 of the 240mm How M1).

Used in the Colmar pocket, this container was found in Durrenentzen (68) after the liberation battles. Our warmest thanks go to the Pfeffen family, who donated it to us in 2021.

Condé-Dragons ou 2ème Régiment de Dragons.

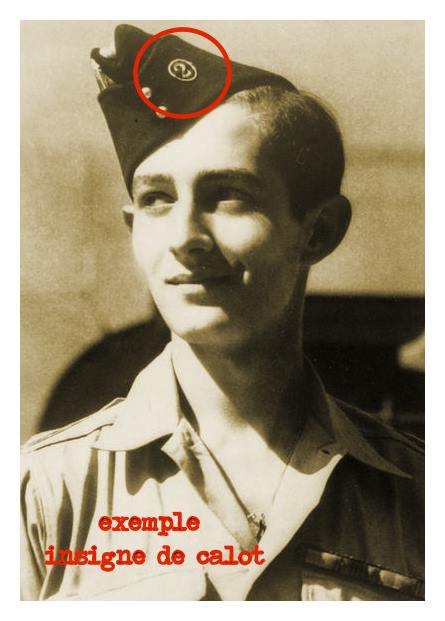

Insignia for the cap (small roundel), for the chest, buttoned onto the shirt with a small leather tab, and for the chest, sewn onto the Field Jacket.

Insignia made by the regiment’s own craftsmen

History :

From January 20 to February 5, 1945, this Regiment took part in the total reduction of the Colmar pocket, with its squadrons engaged in fierce fighting in the workers’ housing estates of the potash mines near Mulhouse. He played a major role in the rapid exploitation of the area, which, after the enemy had broken through at Cernay, led to the junction of the forces of the 1st French Army, converging on Rouffach from the south and north.

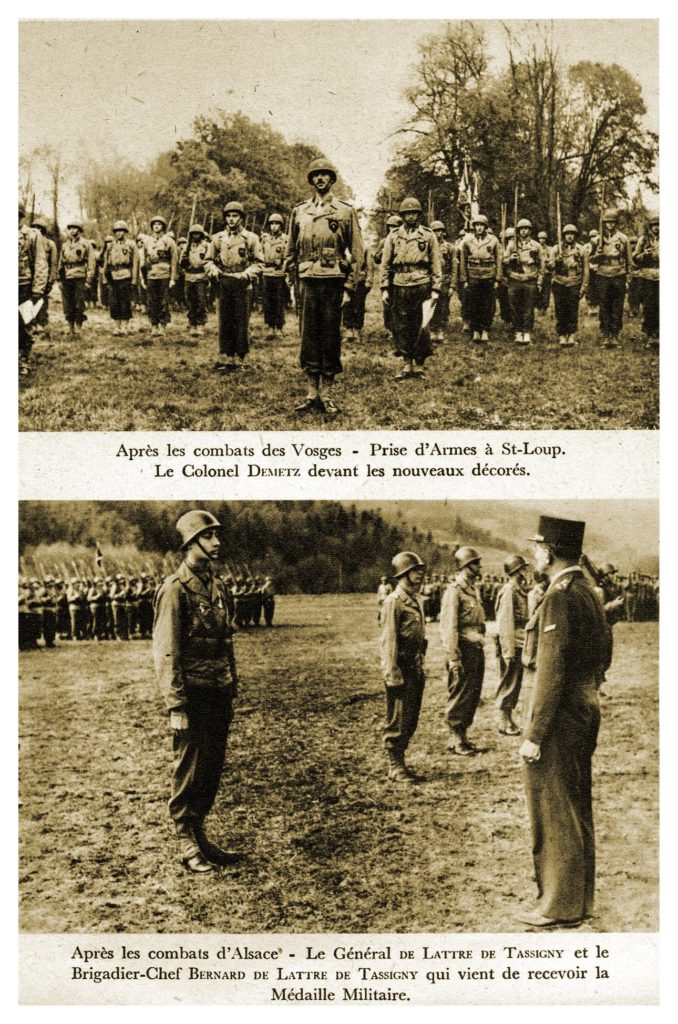

For the record, General de Gaulle granted an age exemption to Bernard De Lattre, son of the General, who was judged too young to join the liberation army, but showed unfailing determination to fight. He was assigned to the 2nd Dragoons on August 8, 1944. He was seriously wounded during the fighting to liberate the town of Autun (71), on September 8, 1944. He was awarded the Military Medal by Colonel Demetz, commander of the 2nd Dragoon at the time, at a parade in Masevaux(68) on February 23, 1945, in the presence of his father (see photo below).

The oldest French cavalry regiment, for nearly 2 centuries at the forefront of the battle against France’s enemies, the Régiment de Condé became the 2nd Dragons.

When war was declared in 1939, the 2nd Dragoons were garrisoned in Paris. After the war, when the Regiment had accomplished its glorious mission…it was to return to Paris.

In 1940, its standard read: Zurich 1793 – Hohenlinden 1800 – Austerlitz 1805 – Jena 1806 – Ypres 1914 – Flandres/Champagne 1918.

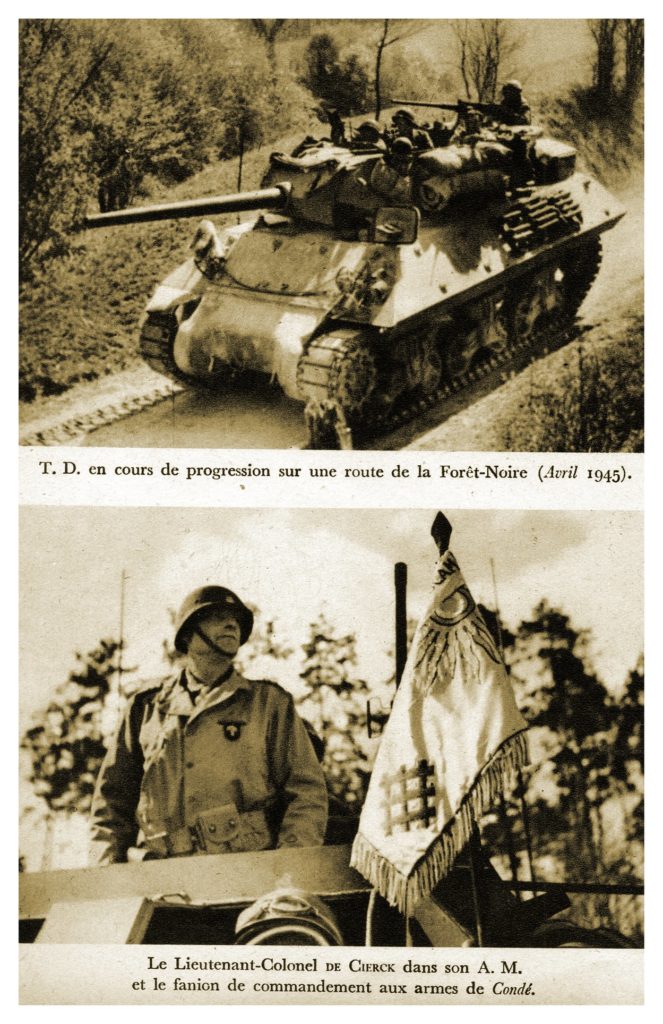

Officially reconstituted in Sfax (Tunisia) in December 1943, the 2nd Régiment de Dragons became the Régiment de Tanks Destroyers (TD)…the first nine TD M10s would only arrive on May 3, 1944… On June 1, General de Lattre gave them 2 months to set up a complete armored regiment (3 TD squadrons, 1 AM squadron, i.e. 36 TDs, 20 M8(AM) self-propelled machine guns and around a hundred other vehicles) in marching order, with all its equipment and well-trained crews.

That’s why his tanks and vehicles will bear names drawn from the wealth and memories of Paris:

The Colonel’s command AM is called “PARIS”.

The TDs take the names of the capital’s monuments: “Arc de Triomphe”, “Louvre”…

The 20 AMs are named after neighborhoods: “Passy”, “Champs Elysées”, “Ile Saint-Louis”…

Jeeps are named after squares, streets or metro stations: “Bastille”, “Rue de la Paix”…

Half-tracks are reminiscent of stadiums or velodromes:

“Vel d’Hiv”, “Parc des Princes”…

Command-cars are reminiscent of racecourses:

“Auteuil”, “Longchamp”, “Saint-Cloud”…

For motorcycles, the names of theaters and nightclubs:

“Maxim’s”, “Bouffes Parisiens”…

Trucks, names of working-class suburbs:

“Billancourt”, “Pantin”, “Surenes”…

And so the men “took” the whole of Paris with them into battle.

The unit returned to French soil in Provence on August 30, 1944 at Beauvallon, before setting off on the roads of France on September 1: BEZIERS – SETE – MONTPELLIER – RHÔNE RIGHT BANK – PARAY LE MONIAL – AUTUN – DIJON – VOSGES – BELFORT – ALSACE – GERMANY – AUSTRIA.

The flag of the glorious Condé-Dragons now bears 2 Croix de Guerre with 4 palms and 4 stars, as well as the Médaille des Evadés.

Sources : Mmcpc – « Condé-Dragons, histoire d’un Régiment 1939 – 1945 » et internet.

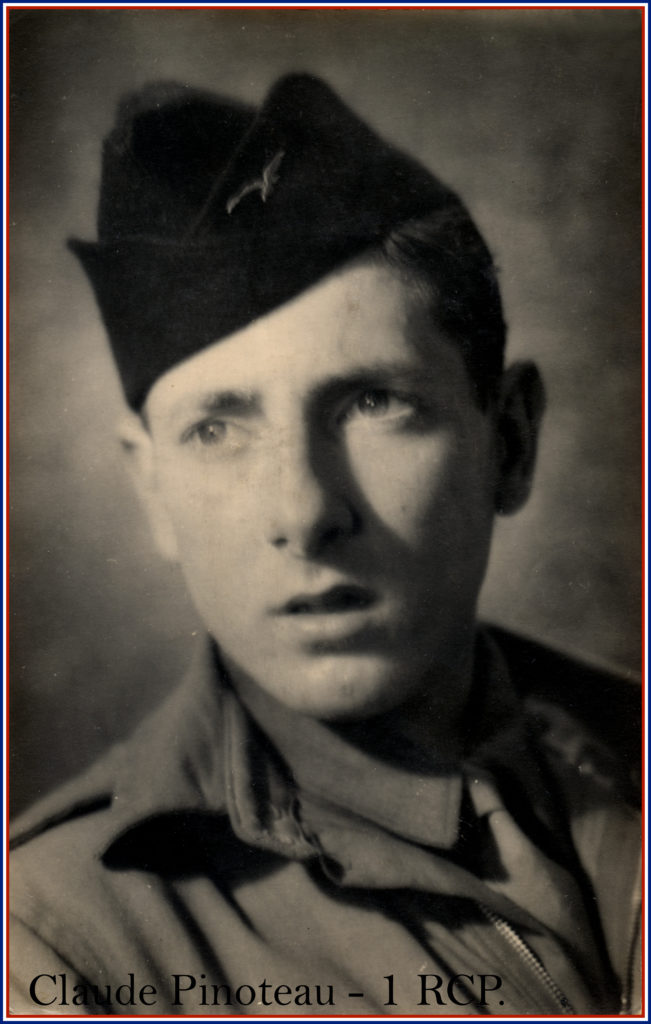

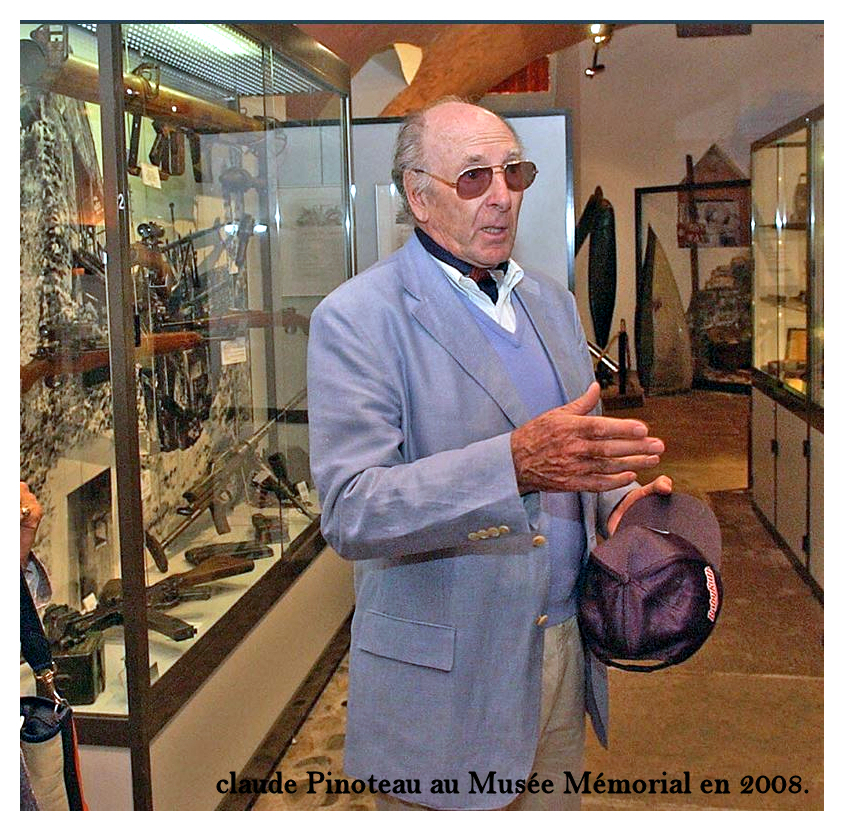

Claude PINOTEAU 1925 – 2012

Claude Pinoteau was born in Boulogne-Billancourt on May 25, 1925.

When Paris was liberated on August 25, 1944, Claude Pinoteau (18) joined the Hémon Battalion with his brother Jack: “We were just kids aged 16 to 18, but we wanted it, we’d had enough of the German occupation and Nazism”.

For him, it was a duty to fight. On one of his visits to the Memorial Museum, he declared: “We wanted to liberate France, for us it was an imperative!

In 2008, he humorously recounted improvised maneuvers with his buddies in the Bois de Boulogne: “I ‘shot’ a colleague several times, but he refused to play dead, so I threw an offensive grenade at him, but just as it exploded my chief warrant officer shouted ‘ceasefire’… that got me 8 days in the brig. I spent 2 days in a sort of horse stall, in the building we occupied in Neuilly, which served as our barracks. One morning, at 2 a.m., we were woken up, collected and given a rucksack… “En avant Marche”! The rucksack had no shoulder strap, so we had to make do with our belts. A whole column of jeeps from the 1er Régiment de Chasseurs parachutistes (1st RCP) had come to pick us up and take us to Lons-le-Saulnier (we traveled all night) where the regiment was stationed.”

“After selecting the “oldest” of the kids we were given bags with new outfits. Then we received intensive training (gymnastics, theoretical studies and weapons dismantling, maneuvers…). One night during a maneuver, we had to slide along a railway track, but it was so dark that we couldn’t see a thing. I launched myself first and landed badly on a concrete slab… dislocated ankle, crutches and confined for 3 weeks. What a disappointment it was to see my comrades go to the front, without me, during my convalescence”.

“Too impatient to join them, I managed to get into a recovery dodge that took me to Alsace to meet them in Erstein (67), where I really realized what war was all about. I remember the noise as we approached the front line: you’d hear muffled noises in the distance, then they’d get louder and louder, and the closer you got the more you could make out the detonations and automatic weapons fire. We were aware of death, but we had confidence in ourselves and above all we wanted to fight.”

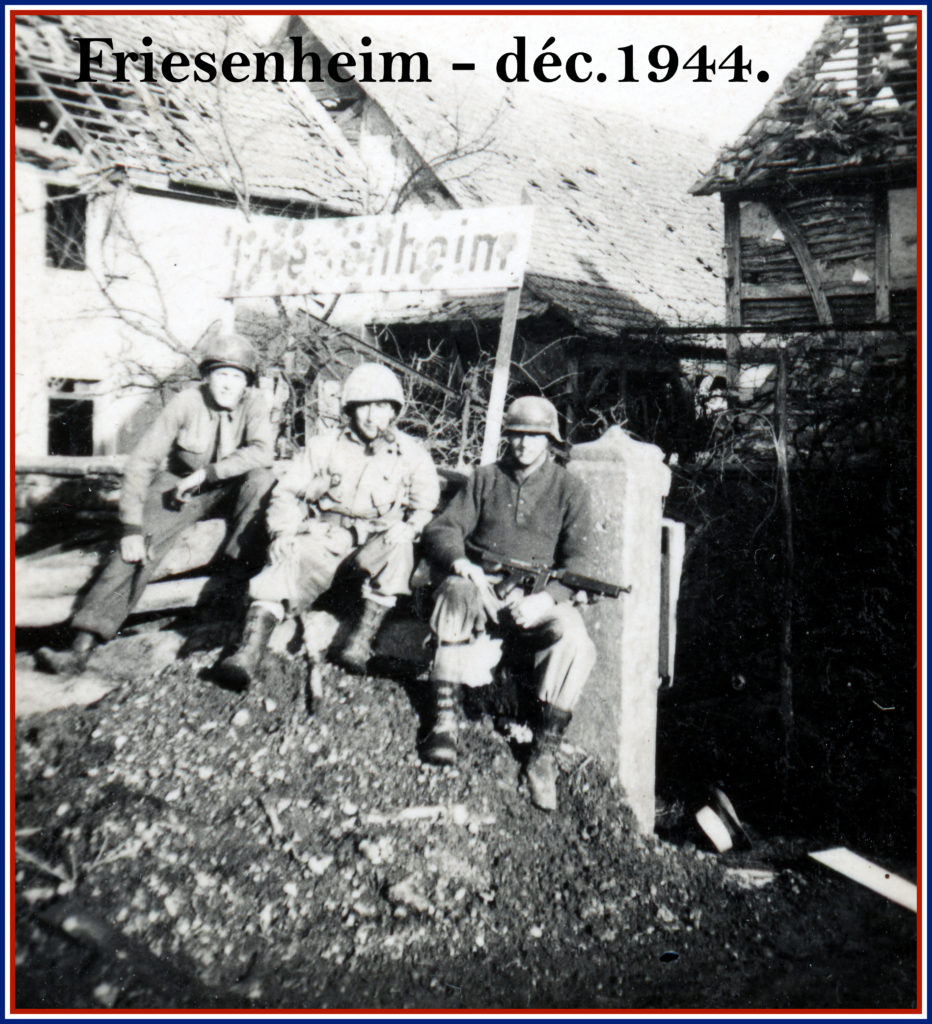

Claude Pinoteau experienced his baptism of fire in Alsace, at Friesenheim in the Benfeld sector in December 1944.

Despite the war, Claude Pinoteau tells us a funny anecdote that happened to him in the Erstein sector: “I met a farmer and asked her to fill my can (of snaps) with milk, because when I was a child I loved milk-grenadine (during the war milk in Paris was scarce). As soon as it was full, we headed straight back to the Rhine, where fire was coming from all sides. My comrade asked me to pass him my canteen of snaps, and he immediately spat out the milk it contained.

“Later, the medic was killed and had to be replaced. Having been a boy scout, I was automatically appointed. A quick review of the various medical instruments and I had to take on the job. In very serious cases, you always have an energy you don’t know you have, an extraordinary composure. I was confronted with severe injuries, but I found the strength because my mission was to save my comrades.”

The fighting in Jebsheim from January 26 to 29, 1945 was terrible, with night and day battles from house to house under a deluge of fire and steel. Claude Pinoteau told us about the thwarted German ambushes and their camouflage system in the snow. For him, the improvised 1st aid post on a farm was a living hell, as the arrival of the wounded never stopped: “the dead were piled up outside, and the snow covered them during the night”… memories of horror and pain for Claude Pinoteau, with the loss of many comrades.

In 1948, he started out as a prop maker and stage manager, before becoming an assistant film director. In 1973, he directed his first feature film. A successful director (Le Silencieux, La Gigle, La boum, L’étudiante, among others), in 1991 he made an autobiographical film, “La neige et le feu”, in which he recalls his experiences in the 1st RCP, which had a strong impact on his adolescence and on an entire generation.

He died on October 5, 2012 in Neuilly-sur-Seine in his 88th year.

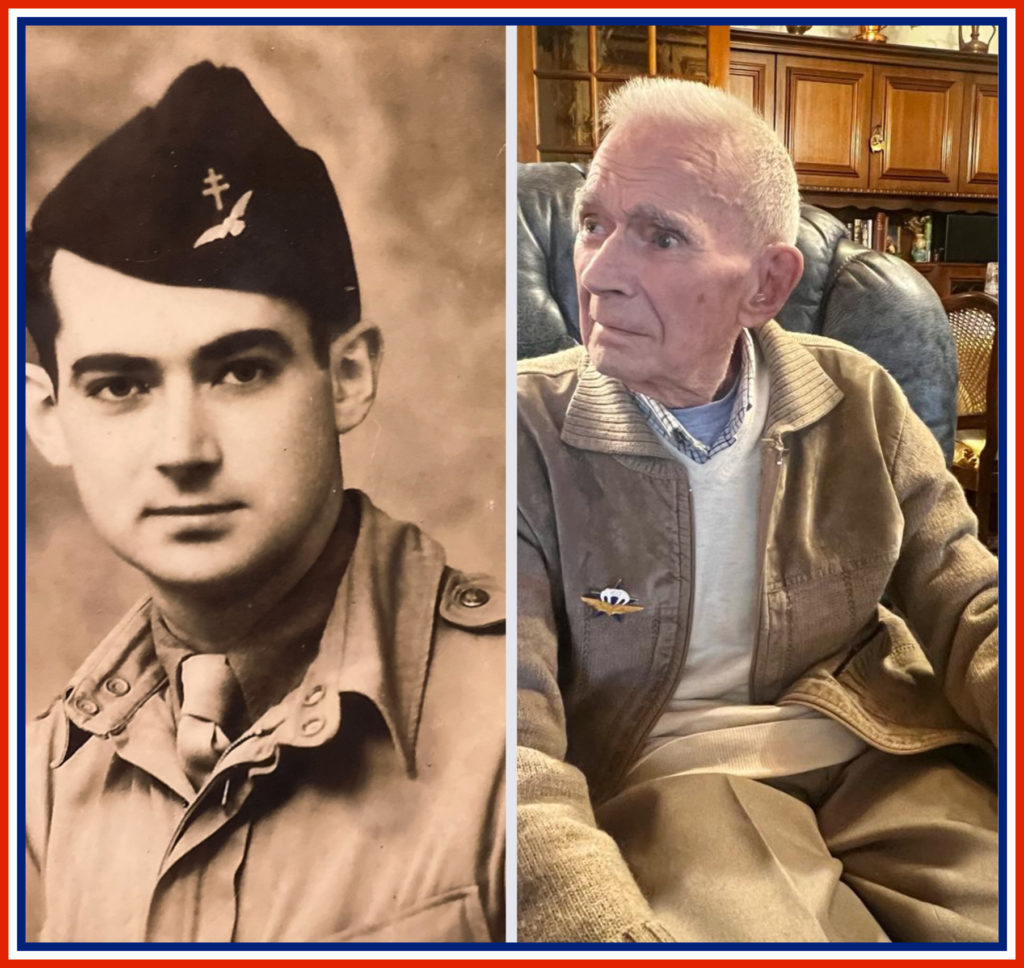

Claude FAUDOT 1917 – 1983

Claude Faudot was born on November 7, 1917 in Aurillac, Cantal (15).

He enlisted voluntarily for 6 years from September 20, 1939, and entered the Ecole Spéciale Militaire (ESM) at Saint-Cyr.

He entered the Versailles Villacoublay Air School on October 4, 1939 as a student pilot.

Present at Ecole de pilotage n°101 at Saint-Cyr on March 01, 1940.

Promoted to Second Lieutenant Cadre Naviguant on March 20, 1940, he was posted to the Orly flying school on April 1, 1940.

Withdrawn to North Africa (AFN), he embarked at Port-Vendres on June 14, 1940 and landed at Oran on June 16, 1940.

On December 4, 1940 he was assigned to the GT 2/32 Transport Group in Agadir, then to the GT 1/32 in Casablanca on December 26, 1940 as an observer.

He was promoted to Lieutenant TD Cadre Naviguant on March 30, 1942.

On February 18, 1943, he was assigned to GT 1/15, which he did not eventually join.

At his own request, on March 15, 1943 he was transferred to the Bataillon Chasseurs Parachutistes n°1 (BCP n°1) in Fez.

He was seconded to the depot school of the 1st BCP to take the Brevet de Parachutiste tests.

He was awarded the brevet parachutiste n° 774.

The 1er BCP was disbanded on May 1 and officially became the 1er RCP on June 1, 1943.

He was assigned to the 7th Company (in charge of the signals platoon).

It moved with the 1st RCP, from Fez to Oujda by rail, from October 6 to 7, 1943.

With the Oujda-based 1st RCP, he reached St-Pierre St Paul (Algeria) from December 19 to December 20, 1943, from where he reached Bordj Menaiel (Algeria) by road on January 7, 1944.

From Bordj Menaiel (Maison Blanche) he and the 1st RCP flew to Trapani in Sicily on April 7, 1944, where training continued.

On July 11, 1944, he arrived in Rome with his regiment.

September 5, 1944 was a great day, when he landed in mainland France at the Valence-Chabeuil airfield in the Drôme region, to take part in the Liberation of France.

The 1 RCP from Valence then headed for Faucogney in Haute-Saône by road from 28 9 to 1 101944.

The 1 RCP prepares for combat and experiences its baptism of fire in the Vosges.

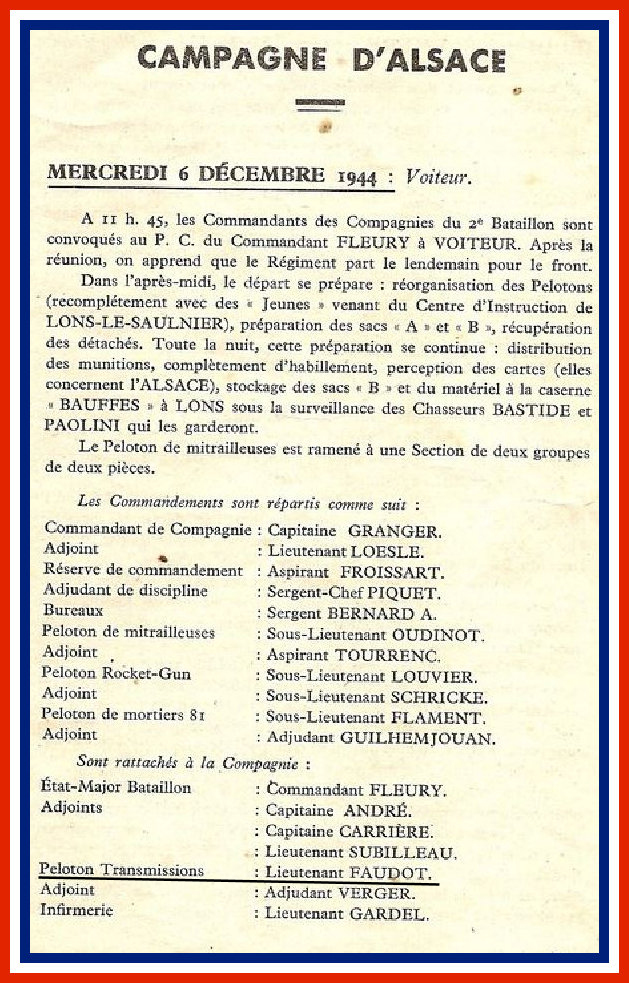

Lieutenant Faudot took part in the Vosges campaign from October 3 to 24, 1944, with the 7th Cie as head of the signals platoon.

He took part in the fighting in the Géhan forest, on the Col du Mesnil, and on hills 1008 and 1111.

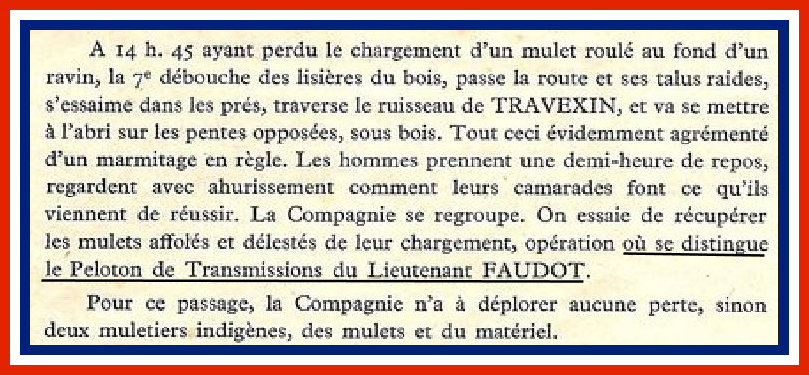

On October 16, 1944, during the attack towards the Col d’Oderen (68), he had to force his way through the Col du Mesnil in order to reach the nearby coastline via côtes 1008 and 1111, under a deluge of fire. A passage in the 7th company’s marching diary refers to Lieutenant Faudot and his platoon that day:

For his actions in the Vosges he was cited for the first time:

Citation to the Division Order OG n°21 dated 12.3.45:

“Signal officer of the Battalion showing the finest qualities under fire. Has worked tirelessly during the operations of October 1944 to maintain communications in particularly difficult and often perilous conditions. On October 17 and 18, 1944, its platoon reinforced an FV company at the Gehan position (hill 1008). Distinguished himself by repelling severe counter-attacks and inflicting significant losses on the enemy”.

This citation includes the French Croix de Guerre with silver star.

On October 24, 1944, it moved from Travexin to Saulx de Vesoul, then from Vesoul to Voiteur (Jura) by road on November 6, 1944.

The regiment was set off to fight in Alsace, and moved from Voiteur to Gerstheim on December 7 and 8, 1944.

Lieutenant Faudot took part in the Alsace campaign from December 8, 1944 to February 19, 1945.

He took part in the fighting at Benfeld(67), Orbey(68), Lapoutroie(68), Jebsheim(68), Widensolen(68) and Colmar(68).

For his commitment to fire, he is cited a second time:

Citation to the Regimental Order OG n°3 dated May 7, 45

“Officer in charge of the Battalion transmission platoon. Participated brilliantly in the entire Alsace campaign. An example of self-sacrifice and quiet courage, he constantly maintained his transmission network under difficult and perilous conditions, in particular from January 25 to 27, 1945, at the Jebsheim mill, where the spotted post was subjected to heavy enemy artillery fire. Ended the campaign with a decimated platoon, but still animated by the finest spirit of sacrifice, thanks to the example set by its leader”.

This citation includes the French Croix de Guerre with bronze star.

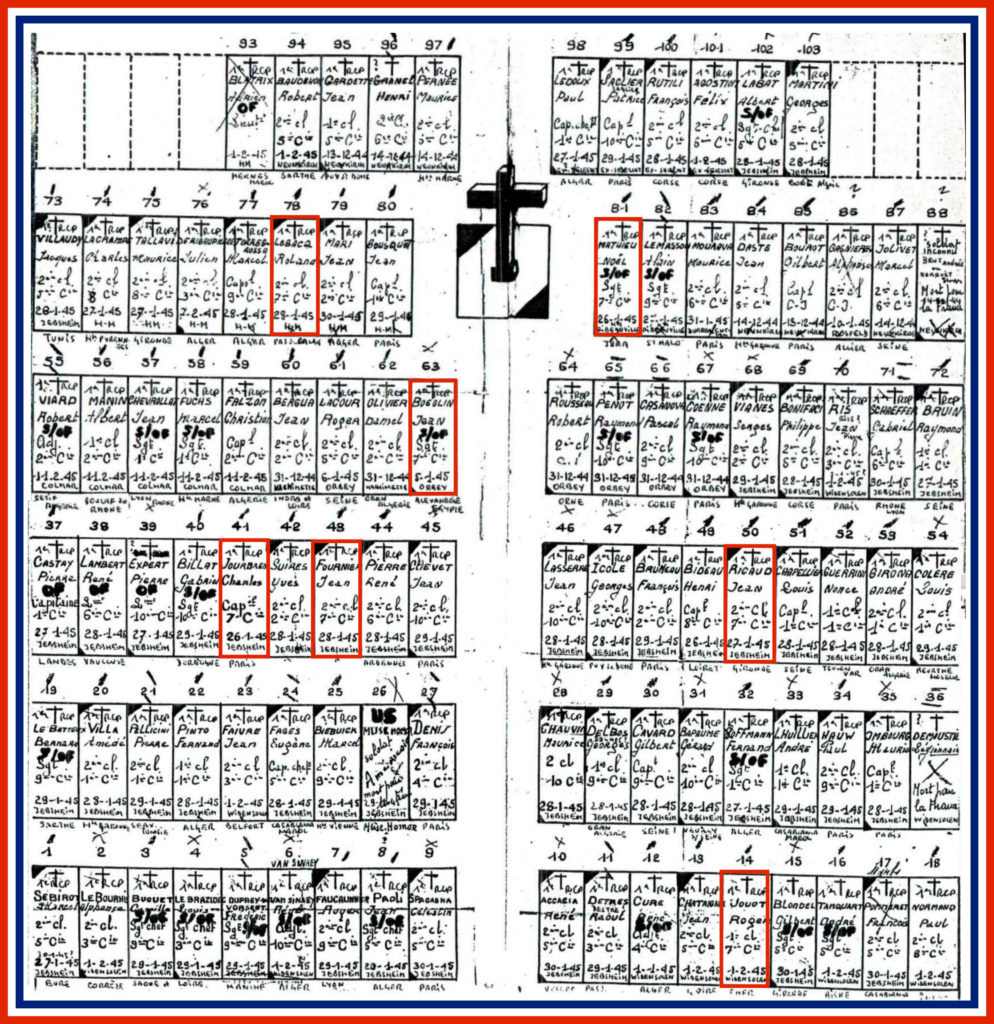

The photo above shows Lieutenant Claude Faudot visiting the graves of his comrades killed during the Alsace campaign at the provisional cemetery of the 1st RCP at Bergheim (68). In the background, the pennant of the 7th company can be seen leaving the cemetery.

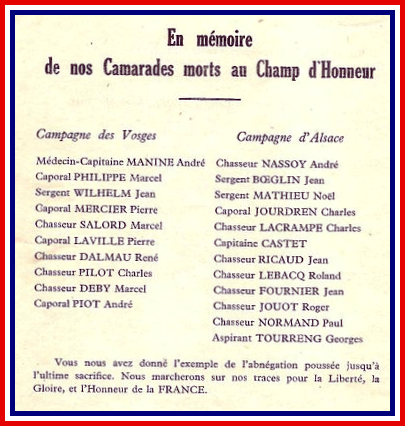

Soldiers of the 7th Company of the 1st RCP Died for France during the Vosges and Alsace campaigns.

He married Simone Mosnier on March 10, 1945, with whom he had two daughters and a son.

After the end of the war, he returned to the air force as a student pilot, joining Groupement de Bombardement n°11 on July 25, 1945.

On May 18, 1946, he joined the Radio Navigator School in Pau, then the Parachute School in the same town, and was seconded to the 25th Airborne Division Staff.

He was promoted to Captain on October 19, 1946.

After passing through the Base Ecole 705 at Cognac and 706 at Cazaux in 1947-1948, he joined the Groupe de Transport 1/61 “TOURAINE” at Orléans on September 1, 1949.

Assigned to GT 1/63 “BRETAGNE” at Thies in Senegal on May 4, 1950, he arrived there on May 11, 1950.

He returned to France on May 29, 1953, and joined the 61st Transport Wing on October 13, 1953.

He was promoted to Major on January 01, 1954.

He arrived in Saigon in July 1954 and left Indochina in January 1956. From 1956 to 1960 he was stationed in Casablanca, Morocco.

On June 28, 1960 he landed in Marseille and was posted to the Saint-Dizier base until February 1964, when he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and left the French Air Force after 25 years (totalling 825 flying hours) of loyal service to France.

He died on August 11, 1983 in Arcachon (33).

His decorations :

Chevalier de la LEGION d’HONNEUR

Croix de guerre 39/45 avec 1 étoile d’argent.

Croix de guerre 39/45 avec 1 étoile de bronze.

Médaille Commémorative française Guerre 1939-19345 avec Barette « Libération ».

Médaille Coloniale.

Médaille Commémorative des opérations de Sécurité et de maintien de l’ordre en Algérie avec barrette « Maroc ».

sources : photo 1RCP/ECPAD – SHD – Journal de Marche de la 7ème Compagnie 1944-1945 – Historique du 1er RCP – colorisation klm127.

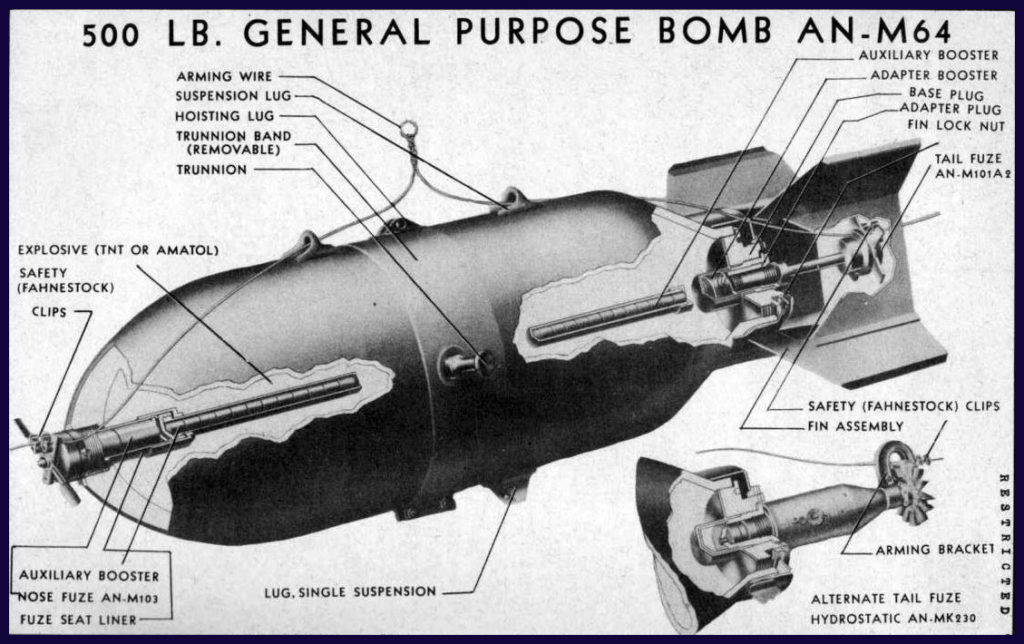

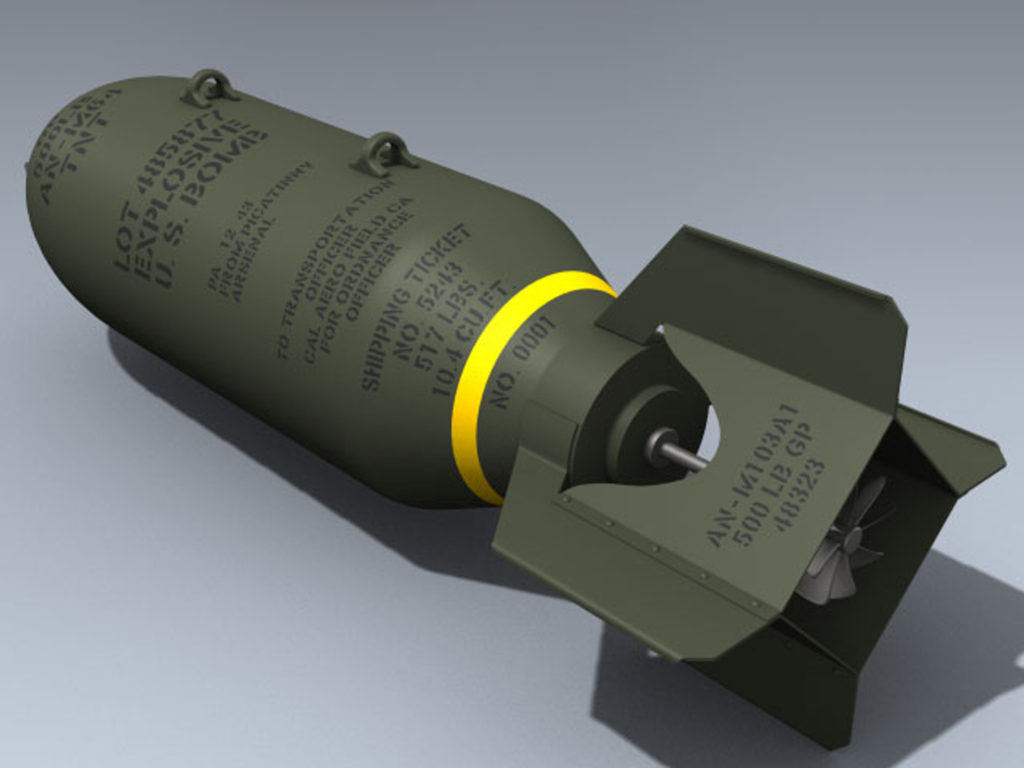

BOMBE US de 500 lb AN-M64

American GP AN-M64 bomb weighing 500 Lbs (226 kg).

The explosive charge represents 50% of the total weight (approx. 123 Kgs).

3 types of explosive were used in GP (General Purpose) bombs:

…Trinitrotoluene (TNT).

…Amatol (a military explosive composed of a mixture of TNT and ammonium nitrate).

…Composition B (RDX), which explodes faster and more violently than TNT.

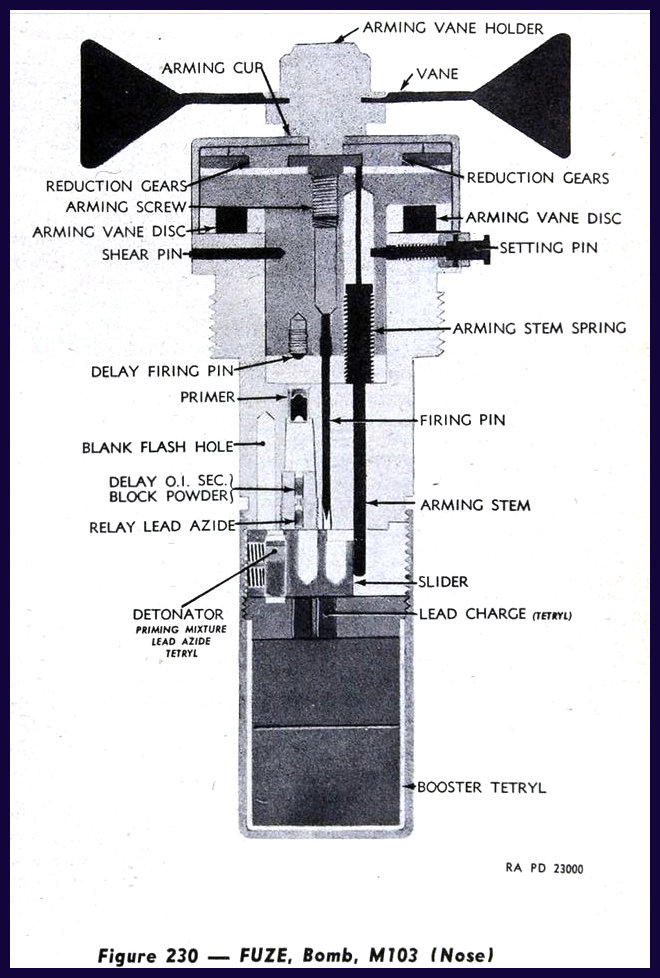

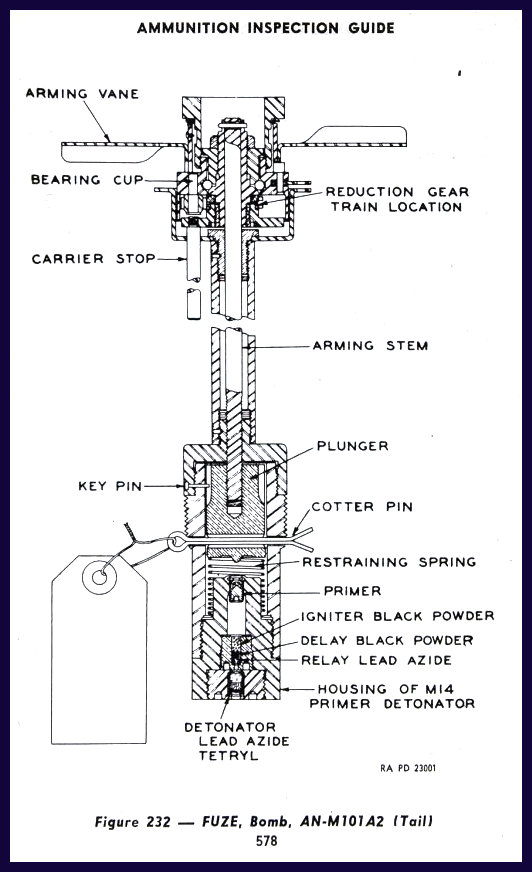

The bomb is primed by an AN-M103 head fuse and an AN-M101A2 tail fuse.

The two upper suspension rings are used by American aircraft, and the single lower ring by British aircraft.

This type of bomb could be used by all Allied fighter-bombers.

Republic P-47 Thunderbolts were generally armed with a bomb of this type under each wing.