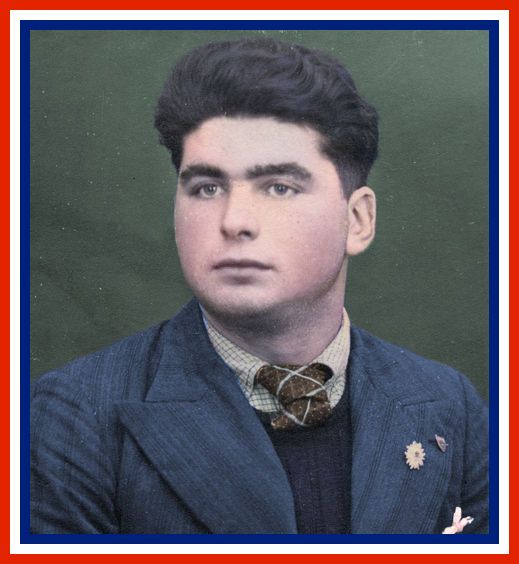

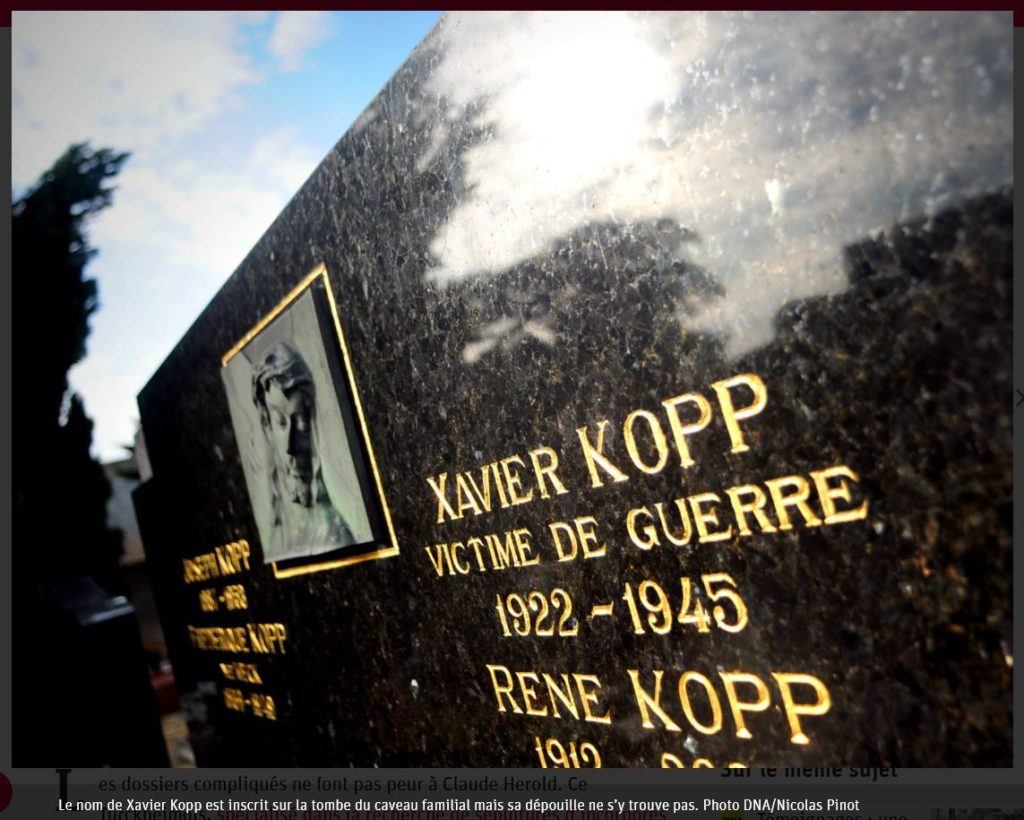

Xavier KOPP 1922 – 1945

The “Xavier Kopp” mystery…drafted, escaped and killed by an American soldier in Colmar on February 4, 1945…

Forced into the German army in 1942, Xavier Kopp, a child from Niederhergheim (68), escaped from his unit on leave in Alsace, just before the fighting began in the Poche de Colmar. Two days after the liberation of Colmar, he was executed in the street by an American soldier. His remains have never been found.

His story…

Born in Niederhergheim in 1922, he was the son of village blacksmith Joseph and Frédérique Weck from Gueberschwihr. The couple had eight children, including four boys. Only Xavier was captured by the occupying army. The Kopps weren’t too fond of the Germans. Their hearts were French, especially since the Nazification of the region.

Deported for being a hothead…

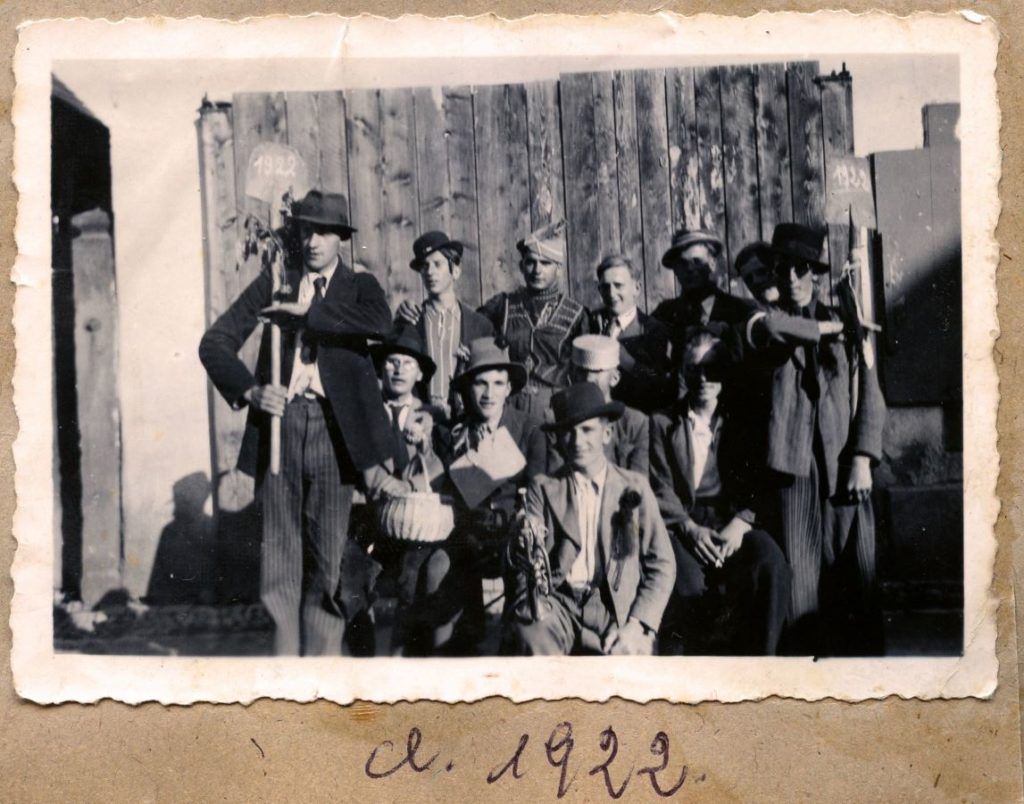

Xavier was a hothead. In one of his books (*), historian Nicolas Mengus recounts the opposition of several young people from the village, all born in 1922, to joining the German army. It was the end of 1942, shortly after Gauleiter Wagner’s decree of August 25/1942 instituting forced conscription. “When Xavier Kopp was called up to the Wehrmacht draft board, he and seven of his comrades refused to sign their wehrpass (military booklet). The penalty was immediate: internment in the Schirmeck reform camp(67). But this was just a hiccup before the draft.

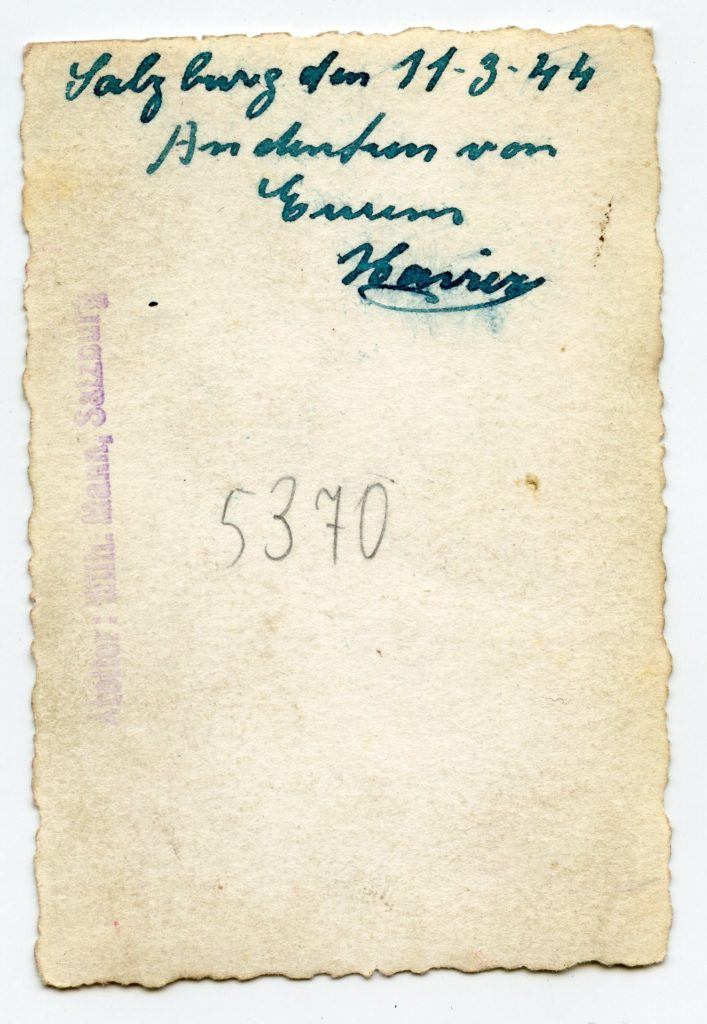

From September 19 to October 2, Xavier Kopp was interned in the Bas-Rhin security camp, then forced to join the German army. He was drafted into the 2nd Gebirgs-Division (mountain troops made up mainly of Austrian soldiers), but we know nothing about his background or which regiment he joined. The 2nd Gebirgs-Division was stationed in Finland.

Back in Alsace in September 1944…

Xavier Kopp returned to Alsace on leave in September 1944. He decided not to return to his regiment, and initially went into hiding in his mother’s native village. In a precious handwritten account from 1947, Joseph Kopp confirms that his son managed to desert and “hid in Gueberschwihr and then in Colmar with a cousin”.

January 1945, the Poche de Colmar had formed since the beginning of the winter, and the Germans were fortifying this piece of land, which they considered to be an integral part of the Reich. Franco-American forces launch the final offensive on January 20. Grussenheim, Jebsheim, Widensolen and the other villages on the plain were liberated after fierce, sometimes hand-to-hand fighting. On February 2, Colmar flew its tricolor banners after the arrival of General Schlesser’s armored troops from Combat Command 4 of the 5th DB. However, snipers hit the bull’s-eye. The shock battalion and the 1st parachute chasseur regiment are tasked with clearing the town.

“Shot with a rifle”…not really…

On February 4, Xavier Kopp came out of hiding. In the general jubilation that followed the liberation of Colmar, my son had the imprudence to venture out into the street dressed half in civilian clothes, half in German military uniform,” wrote Joseph Kopp in 1947 in a letter to the French Ministry of Veterans Affairs. He was seized by American troops and shot”.

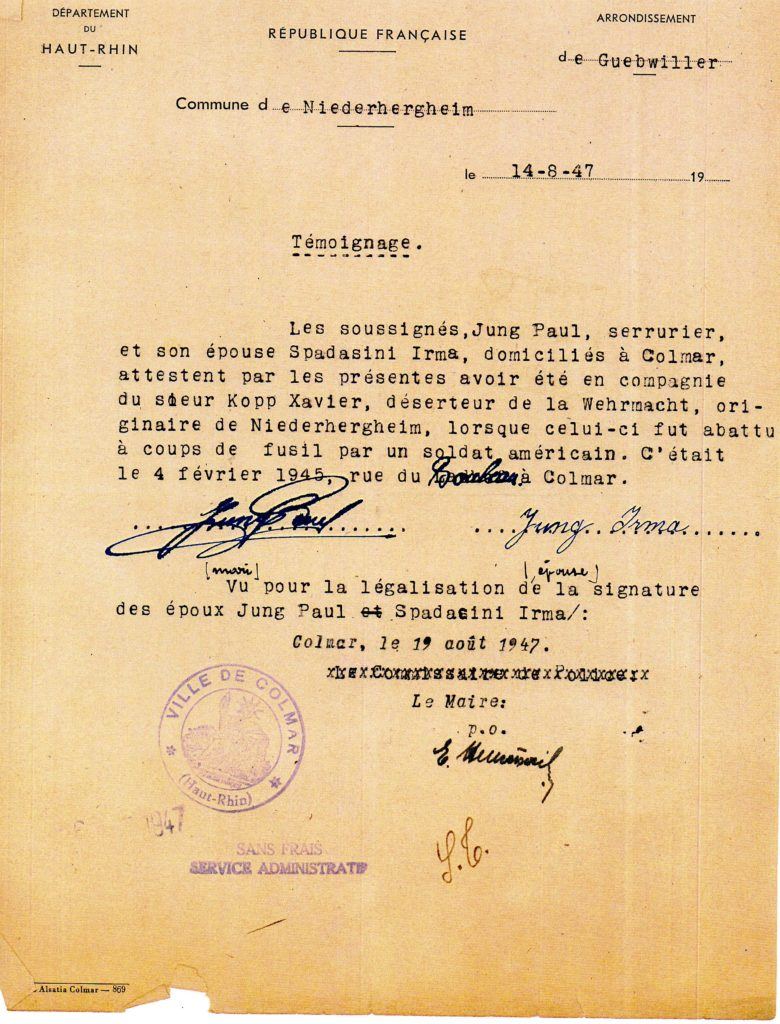

Shot, really? Another account differs. It comes from Irma Spadacini and Paul Jung, who lived on rue du Chêne in Colmar and witnessed the scene. In a document dated August 19, 1947, they testify that they “were in the company” of Xavier Kopp on February 4, 45, when he was shot at point-blank range by an American soldier “on rue du Bouleau, in the Silk district.

In 1957, recognized as “dead for France”…

To make matters worse for the Kopps, in addition to losing their son two days after the liberation, they were unable to mourn because Xavier Kopp’s remains could not be recovered by the family. In August 1947, in a request for a death certificate for his son, Joseph states that his body “taken to an unknown destination, has not been found to this day”. The death certificate was registered in February 1948.

On December 2, 1957, the draftee was recognized as having “died for France”, following an investigation into his character by the prefecture. In a letter to the Minister of Veterans’ Affairs, the State representative stated that the “national behavior” of Xavier Kopp and his family “has been beyond reproach”. Xavier Kopp’s name appears on the local war memorial. It is also engraved on the tombstone of the family vault where his parents are buried.

But what about the corpse?

After checking, the Niederhergheim town hall says it has no record of any burial of the young Kopp in the family vault. Contacted by the Office national des anciens combattants du Haut-Rhin, the Pôle des sépultures de guerre in Metz attempted to locate Xavier Kopp’s perpetual burial plot, without success.

The body could have been buried in a temporary cemetery set up at the corner of Rue du Ladhof and Rue du Pigeon, not far from the Soie district, during the fighting in the Poche de Colmar. Marie-Joseph Bopp confirms this in his book Ma ville à l’heure nazie (La Nuée Bleue). Burials could no longer take place in the cemetery exposed to American artillery fire,” he recounts. The coffins were temporarily buried in the grounds of the war memorial” at Ladhof.

After the war, these coffins were probably exhumed and buried at Ladhof or in military cemeteries. Here again, however, there is no trace of Xavier Kopp in Colmar or at the German necropolis in Bergheim, where some 100 graves are marked “unknown soldier”.

The mystery remains as to his final resting place, where we hope he will rest in peace.

NB: a disturbing testimony:

Marie-Thérèse Fréchard is no longer with us, but she testified in 1995 in the DNA on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of Colmar. This Colmar native was nine years old at the time and remembered perfectly those days of January and February 1945. Her family lived on rue du Bouleau in the Silk district. On February 4, she remembers seeing her neighbors from rue du Chêne coming down the street. They were accompanied by their two children and a young man I didn’t know,” she says. He was dressed in a civilian jacket, but was wearing German boots and pants. No doubt a deserter from the Malgré-Nous who had gone into hiding.

“He threatened everyone”.

Marie-Thérèse continues: “An American non-commissioned officer stopped the group. He asked the young man for his papers and, without explanation, pulled out his revolver and shot him several times. He was killed instantly. A few minutes later, an auxiliary policeman who spoke English explained to the American that he had just killed an Alsatian. The other then panicked and threatened everyone with his gun. We ran and hid in our house.

Xavier Kopp’s Puukko (traditional Finnish knife), engraved with a reindeer, is the insignia of the 2nd Gebirgs-Division.

Xavier had given his knife to his older brother René Kopp (born 1912), who in turn gave it to his son René after the war, who lent it to the Musée Mémorial for display and to perpetuate the memory of Xavier Kopp.

Many thanks to the Kopp family for their confidence in us and for loaning the knife to the Memorial Museum.

sources : Famille Kopp – Claude Herold – DNA – Les Malgré-Nous de Nicolas Mengus (édition ouest France, 2019).

Marie-Madeleine LORENTZ 1940 –

In the ruins of her home in Kientzheim(68), 4-year-old Marie-Madeleine Lorentz came to collect some of her toys, just after the liberation of the village on December 18-19, 1944.

This moment was immortalized by “Miss” Thérèse Bonney (1894-1978), photographer and war correspondent, who covered and followed the advance of the American army on the front line.

Arriving in Alsace with the 7th US Army, then attached to the First French Army, General de Lattre de Tassigny asked her to report on the disaster-stricken villages of the Poche de Colmar.

Touched by the total destitution of the inhabitants on arriving at Ammerschwir (a wine-growing village 85% destroyed), and particularly the plight of the children, she did everything she could to help the local population through her network.

Providing food, medicine and basic necessities, clearing vineyards of mines, supplying work tools and organizing a Christmas party for the children in 1945.

In 1946, she returned to Ammerschwihr to continue her work, providing children with games and clothing, and organizing the arrival of prefabricated houses from the USA to house the inhabitants (it would take some fifteen years to rebuild the village).

In 1947, in recognition of her work on behalf of the devastated people and villages of Alsace, she became an honorary citizen of Ammerschwihr, and was awarded and promoted to Officier de la Légion d’Honneur.

Sa vie : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Th%C3%A9r%C3%A8se_Bonney

As a little anecdote, our “little girl from Kientzheim” came to the Memorial Museum during the summer of 2018 to show her children and grandchildren what she had experienced during the first 4 years of her life.

Sources : photo US NARA & internet – articles DNA – Miss Thérèse Bonney de Francis Lichtlé – wikipédia.

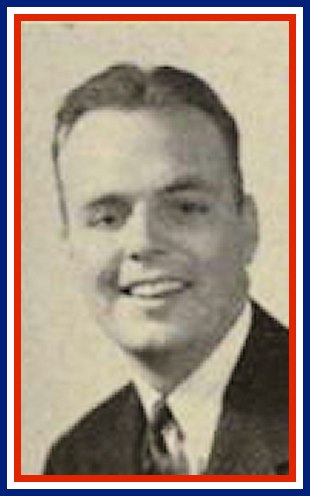

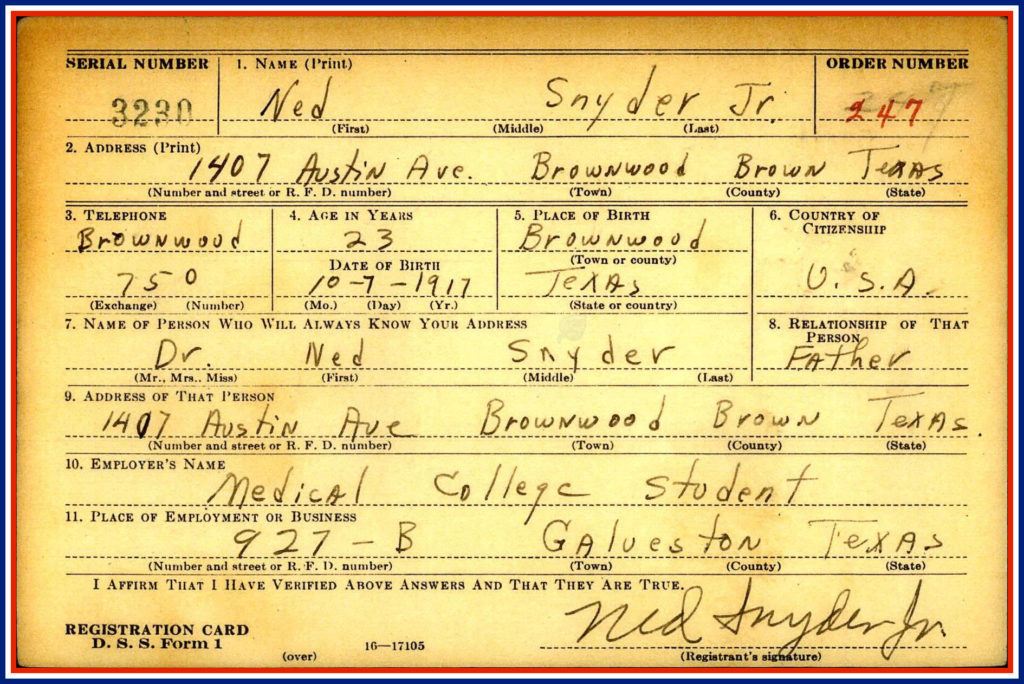

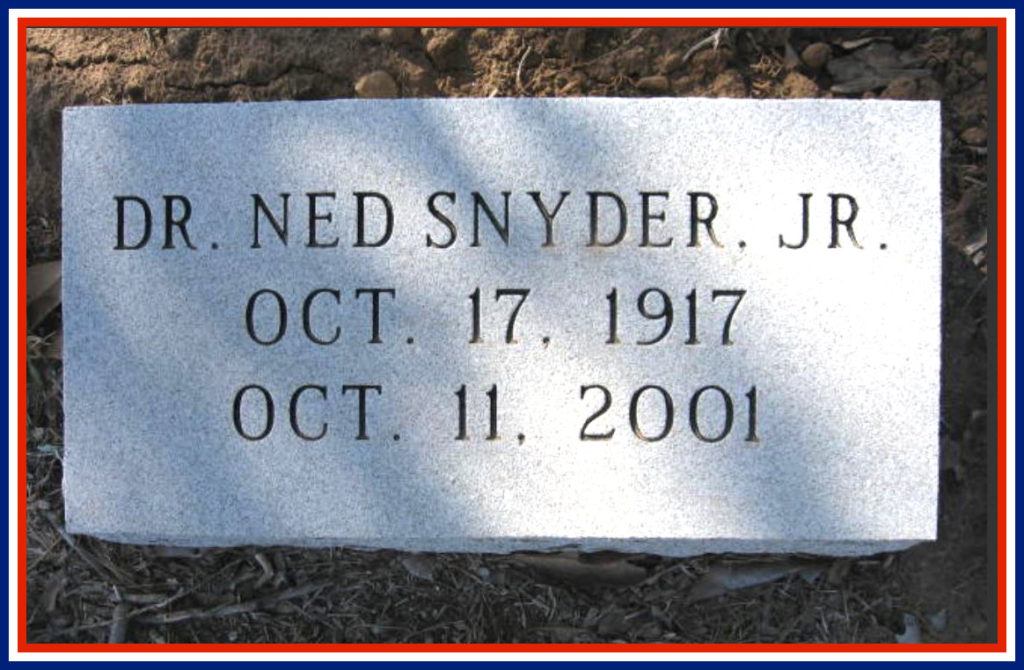

Ned Snyder Jr. 1917 – 2001

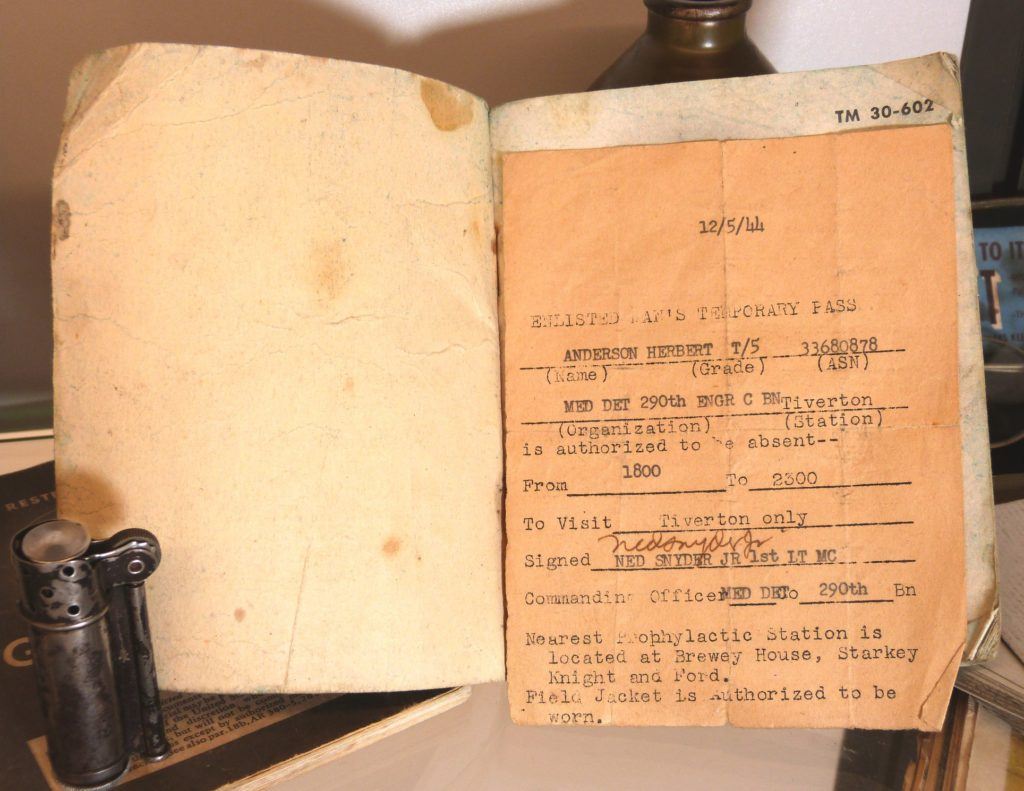

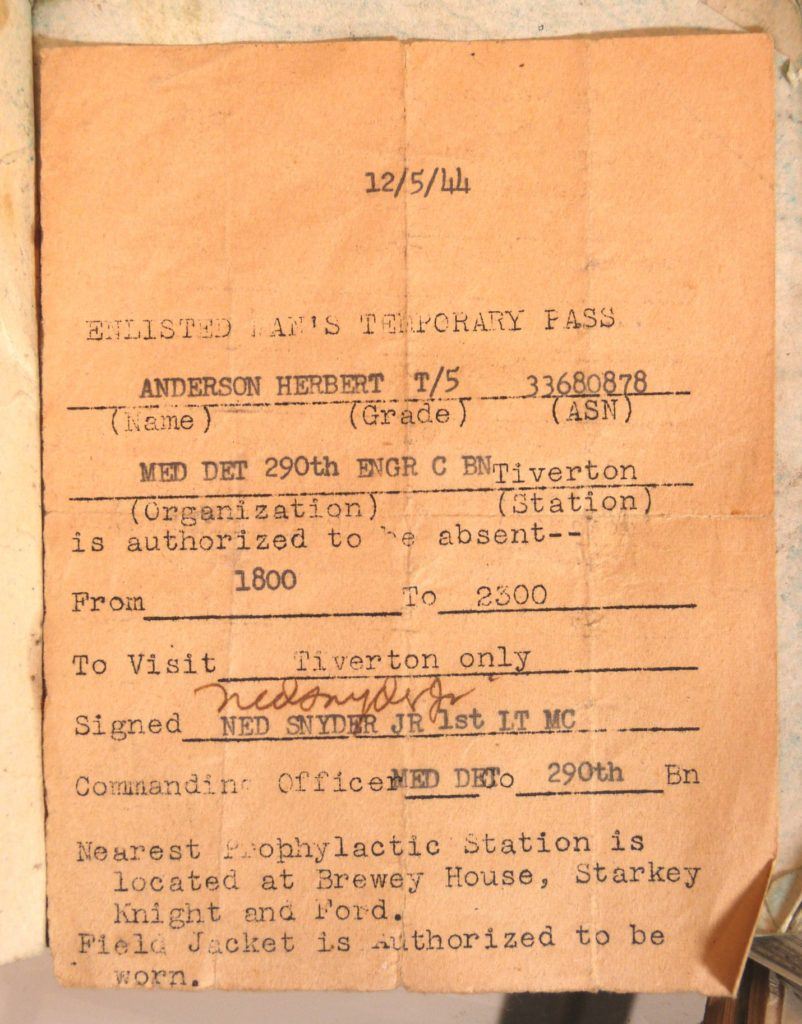

In this French Phrase Book is a piece of paper…a discharge permit issued to Tech/5 Herbert ANDERSON, serial number 33680878, signed by 1st Lieutenant Ned SNYDER Junior, Commanding Officer of the 290th Medical Detachment.

The name may not ring a bell, but it turns out that Dr. Ned Snyder was none other than the first doctor to treat General PATTON after his accident.

Ned Snyder was born on October 17, 1917 in Brownwood, where he spent his entire childhood.

1942 was an important year for him, with his marriage to Beverly Gramann in Austin, Texas, and his graduation from medical school at the University of Austin.

Drafted in 1944, he served 3 years in the U.S. Army until 1947.

At the beginning of his service, he was C.O. (Commanding Officer) of the 290th Medical Det. before being transferred to the USAF.

In 1945, his “last patient” in Germany was a colorful character…George Patton!

On December 9, 1945, shortly before noon, Ned Snyder was on his way to Heidelberg airport, when he happened to arrive at the scene of General Patton’s fatal accident. He was the first doctor to attend to the General, who was suffering from spinal and facial pain.

Ned Snyder is the first to diagnose Patton’s injuries, as he sits motionless in the back of his Cadillac. During the 25-minute drive from the scene of the accident to 130th Station Hospital on the outskirts of Heidelberg, “the old man”, as he was known, gave no sign of complaint or pain!

On his deathbed, he said, “This is a hell of a way to die.

After the war, Ted Snyder returned to his native Texas, and pursued a career in medicine as a doctor. In 1986, William Luce presented his last film “The Last Days of Patton” to the world, showing the role played by Ned, played by Paul Michael, during the general’s last stand!

Ned Snyder died on October 11, 2001 at the age of 84, in Brownwood, his birthplace.

A brief history of the 290th Medical Detachment :

Christmas 1944 in England: The order to leave England for France arrived on December 26, 1944. The Liberty Ship HMS Empire Rapier carried the 290th from Southampton to Le Havre, where it arrived on December 31, 1944.

Departure on January 1, 1945, bound for “Forges les Eaux” for a 4-day bivouac.

Departure on January 6, 1945 for Molsheim. After 6 days’ bivouac in Molsheim, departure for Orbey on January 12, 1945. Arrived in Orbey from Molsheim on January 12, 1945. Attached to the 7th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Infantry Division Us for 10 days in the Hachimette and Lapoutroie sector. Reassigned to the 112th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division from January 23, 1945, after suffering losses alongside the 7th Infantry Regiment in the Bennwihr and Rosenkranz sectors.

Reorganized within the 112th Infantry Regiment in the Orbey sector and began fighting with the 112th Infantry Regiment at the very end of January 1945.

He takes part in the liberation of Turckheim on February 3 and 4, 1945. The objective was reached for the 290th on February 6, 1945, and it was withdrawn from the battlefield the same day, followed by letters of gratitude from General Norman Cota.

The translation of the Authorisation de sortie pour militaire du rang et sous officier :

Enlisted = MDR and S/Off.

ANDERSON Herbert, technician 5th grade, regimental number 33680878

Rank insignia as Corporal, but with Technician T.

Service number beginning with 3 = enlisted or called up for the duration of the war.

290th Medical Detachment, C Engineer Battalion, based at Tiverton

The medical unit of an engineer battalion

Tiverton, Devon (South-West England).

is authorized to be absent from 6:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m.

to visit Tiverton only

Signed Ned Snyder Junior, Lieutenant, Medical Corps

290th (Battalion) Unit Commander

The nearest prohylactic station was at the Strakey Knight and Ford brewery.

A medical department post where soldiers could be screened and treated for venereal diseases. Condoms were probably also available.

There were such posts all over Great Britain and Ireland, where American soldiers were stationed. There were several “Strakey Knight and Ford” breweries in this part of England. The brand was created with the 1st brewery in 1887 and the last production unit closed in 1967.

The combat jacket can be worn.

B” outfit, M41 jacket in place of exit jacket. But the rest of the outfit must be identical to the “A” exit outfit, including the tie.

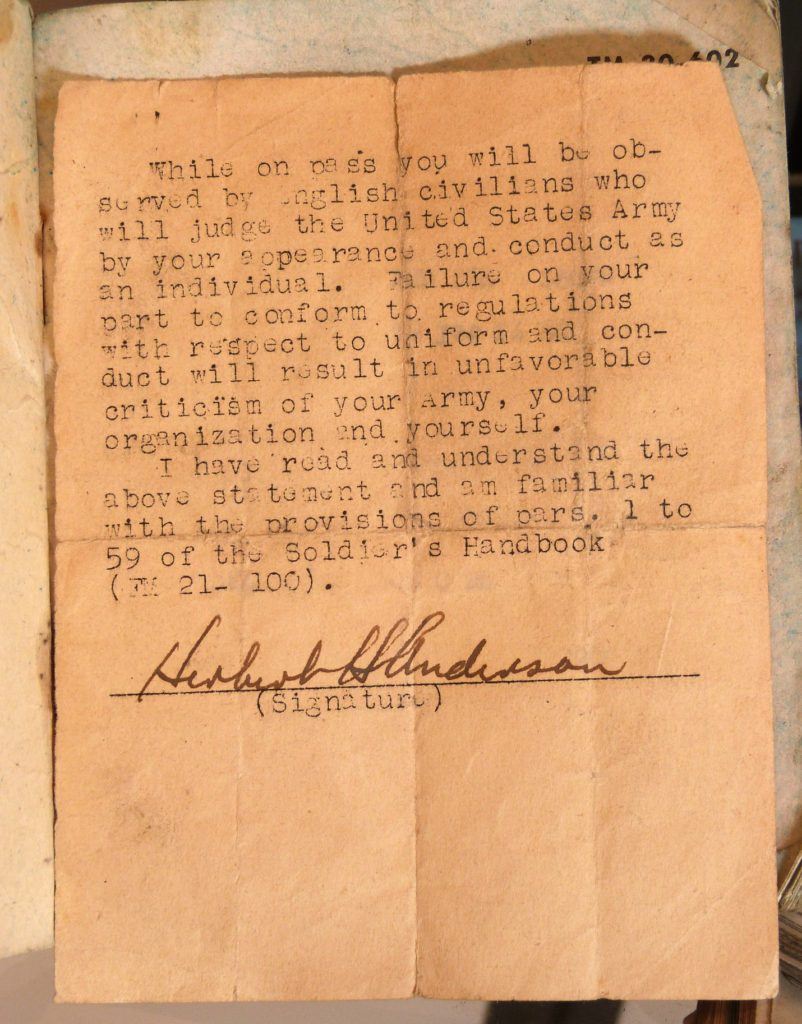

While on leave, you will be observed by British civilians, who will judge the U.S. Army on the basis of your appearance and individual behavior.

Failure on your part to comply with uniform and conduct regulations will result in negative remarks against your army, your unit and yourself.

I have read and understood the above declaration and am familiar with the provisions of articles 1 to 59 of the Soldier’s Manual (FM 21-100).

FM stands for FIeld Manual.

Kosak Freiwilliger – Kosaken-Festungs-Grenadier

Cossack grenadier “Kosak Freiwilliger” armed with a Russian Mosin-Nagant model 1891 7.62x54mm rifle and a Russian Degtiarev DP 28 machine gun of the same caliber at his feet.

He is dressed in a uniform with insignia specific to his ethnic origin (Cossack cavalryman) in addition to the German chest eagle.

He wears a WW1 model 1916 helmet from the army’s reserve stocks (often assigned to secondary or non-combat units).

He belongs to Kosaken-Festungs-Grenadier-Regiment 360.

This regiment was created in France in April 1944 from Cossack volunteers and assigned to the 708 Infantry-Division on the west coast, Bordeau-Royan sector. In October 1944, it was transferred to eastern France and fought in the Colmar pocket.

On February 22, 1945, the unit was transferred to Austria and assigned to the 1.Kosaken-Division, where it ended the war.

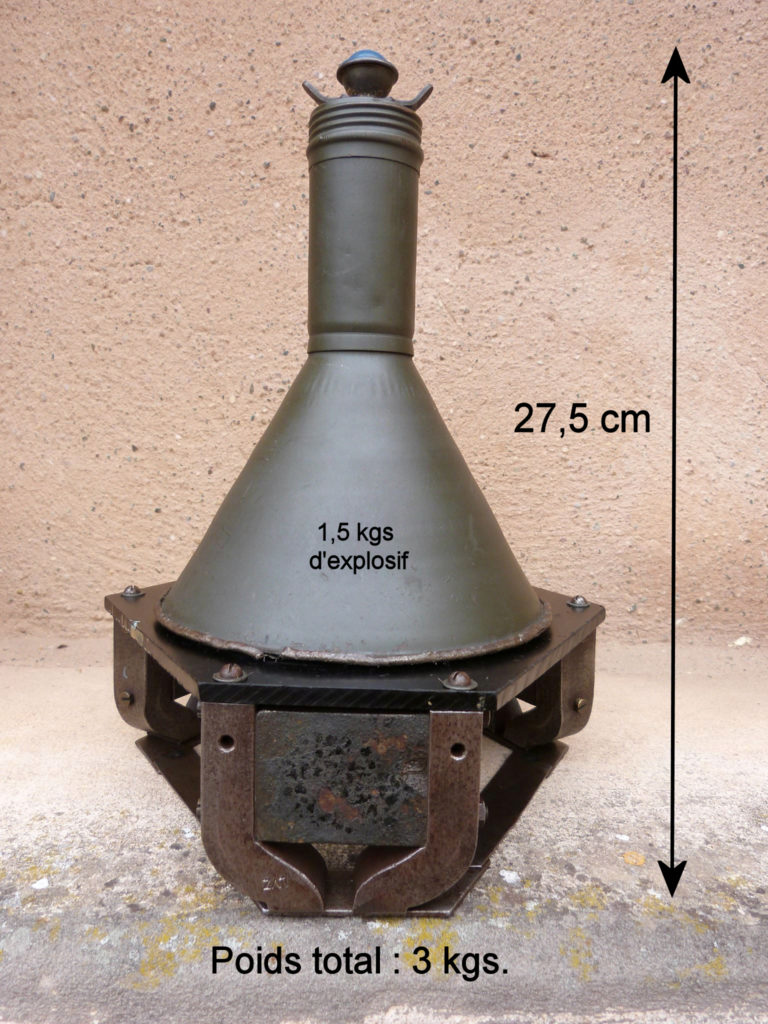

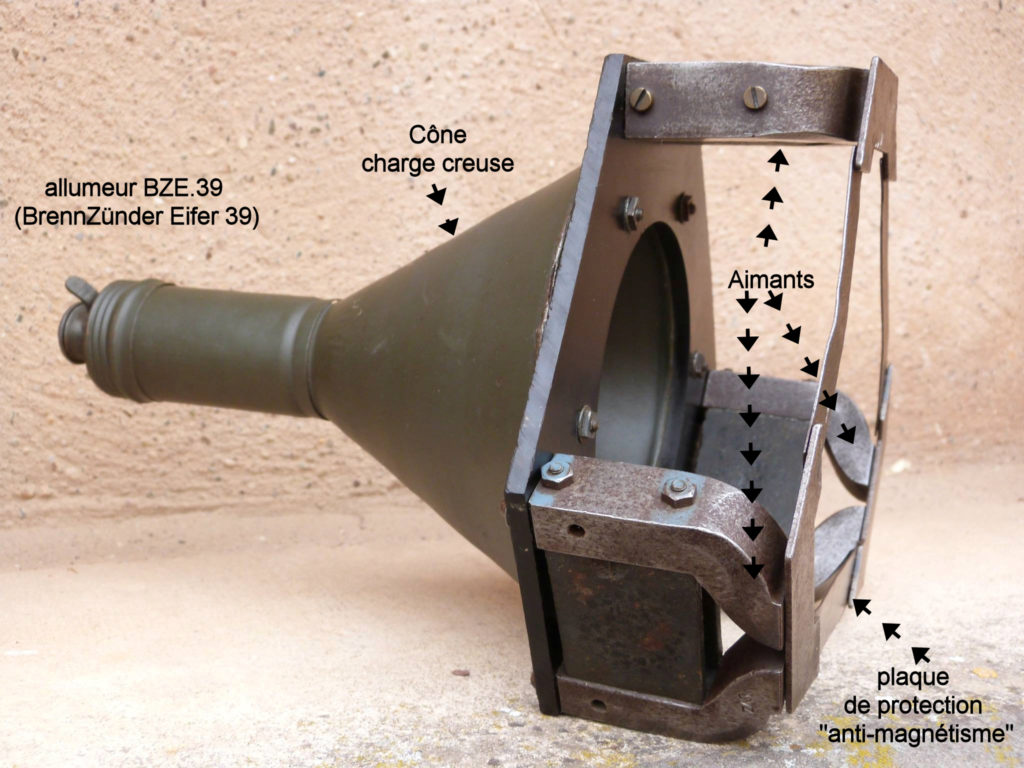

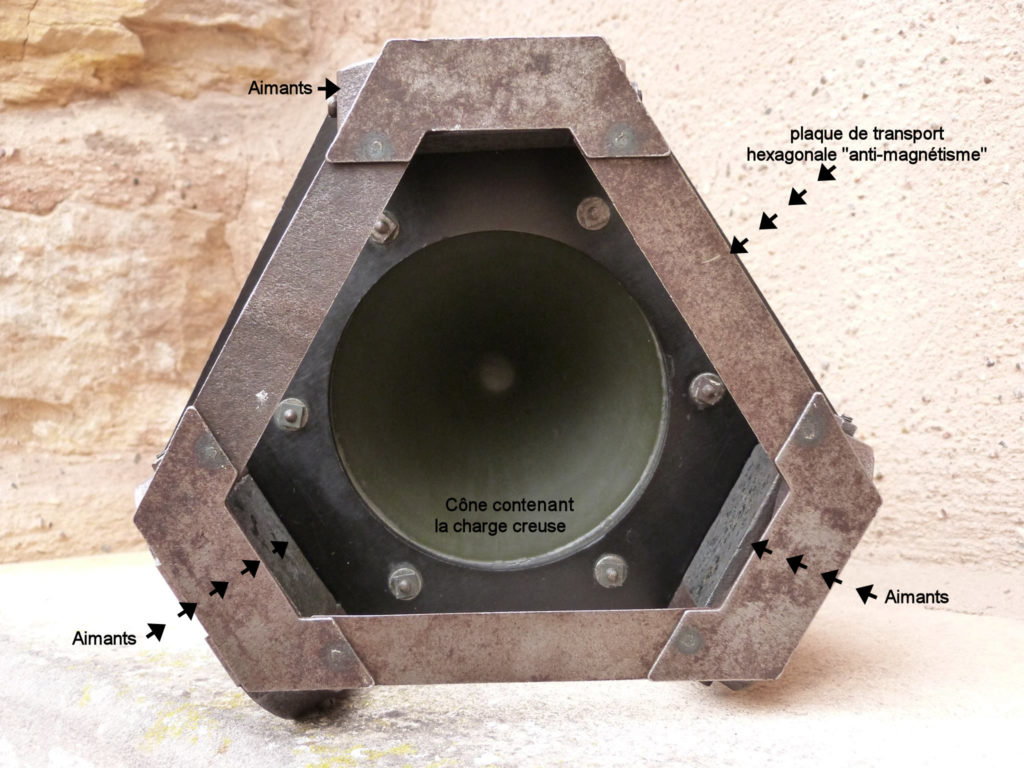

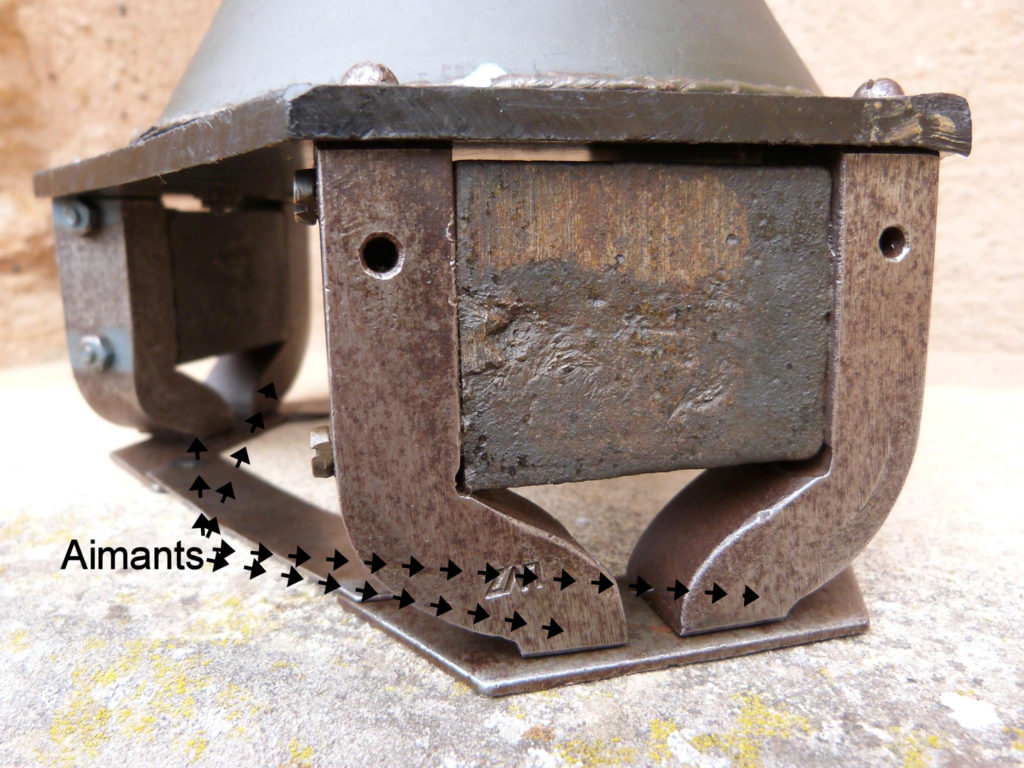

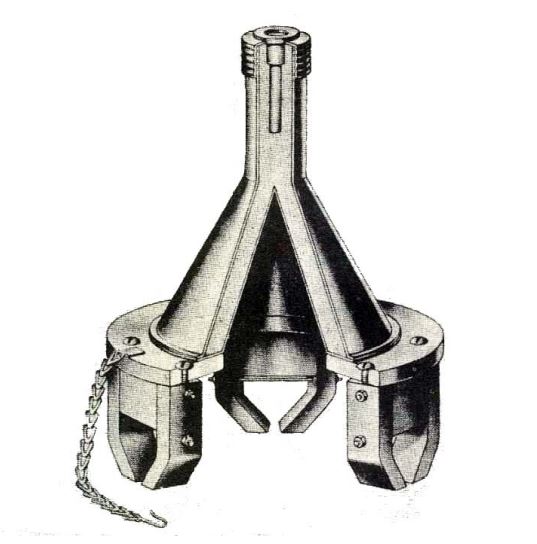

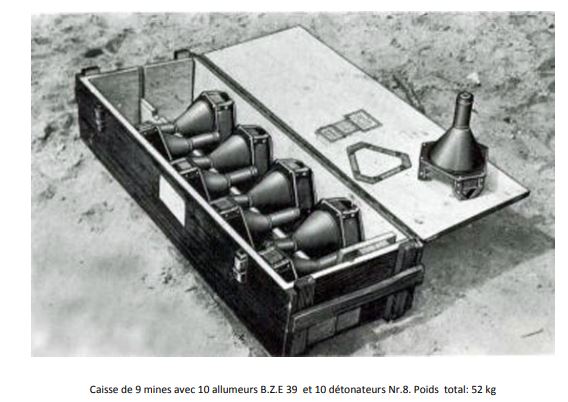

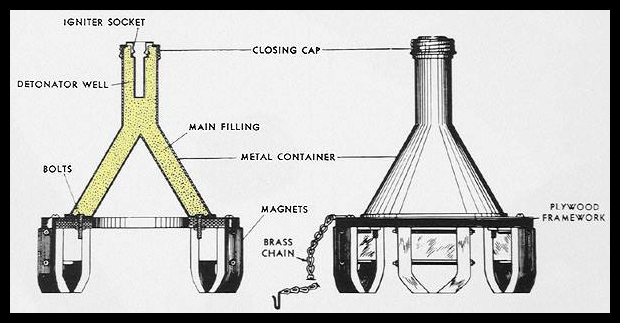

Hafthohlladung HHl-3 (de 3 Kgs).

The “Haftholladung 3 Kgs” magnetic anti-tank mine was issued to the German army in November 1942.

It has a diameter of 15 cm, a height of 27.5 cm and a weight of 3 kg, including 1.5 kg of explosive (RDX-TNT).

It can pierce 140 mm of steel armour or 500 mm of concrete.

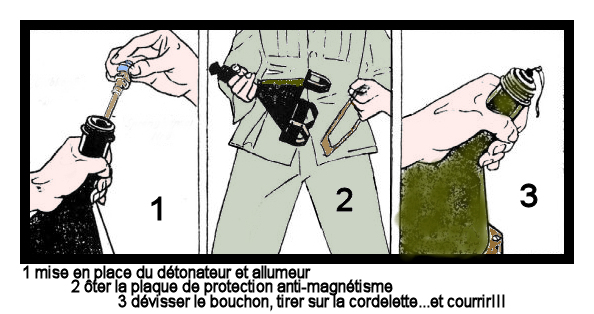

Le système est simple :

- at its base 3 magnets, each with a force of 45 kgs, to adhere to metal surfaces.

- it is equipped here with a BZE.39 (BrennZünder Eifer 39) igniter in yellow (7.5 seconds delay) or blue (4.5 seconds) which is activated after positioning on the target.

- 1 n°8 detonator (Sprengkapsel n°8).

- the cone contains a hollow charge fixed to a bakelite plate (or plywood at the end of the war).

- an “anti-magnetism” protective plate is fitted over the 3 magnets for transport (here in hexagonal form) and removed before use.

German Haftholladung, 3 Kgs magnetic shaped charge.

vidéo : Hafthohlladung Panzerknacker in Action – Magnetic Hollow-Charge Antitank Weapon

SS-Grenadier – Kampfgruppe SS-Regiment « Braun »

Waffen-SS “SS-Grenadier” armed with a 7.92x57mm 98k rifle, fitted with a grenade-launching system.

A carrying case for anti-tank shaped-charge grenades (Groβe-Gewehr-Panzergranaten) lies at his feet.

He is dressed in a Waffen-SS uniform and camouflage smock.

He belongs to an independent combat group (Kampfgruppe SS-Regiment “Braun”, renamed “Radolfzell”) deployed in the Colmar sector from November 1944. The unit suffered heavy losses during Operation Habicht in the Bennwihr-Mittelwihr sector from December 12 to 16, 1944.

This combat group is a heterogeneous conglomerate formed from reserve units and waffen-SS training schools.

Scharfschütze – 198.Infanterie-Division

“Scharfschütze”, sniper armed with a 7.92x57mm G.43 semi-automatic rifle and ZF.4 scope.

Dressed in a camouflaged smock, he carries a pair of binoculars and the scope’s carrying case. A magazine holder specific to his weapon is attached to his belt.

He belongs to the 198 Infanterie-Division created in December 1939. This unit took part in the invasion of Czechoslovakia, Denmark and Greece, before taking part in Operation Barbarossa in 1941 (invasion of the USSR) and fighting until mid-1944 on the Eastern Front, where it suffered heavy losses.

In June 1944, it was reconstituted in the south of France, before being sent to the Colmar Pocket.

Polizei-Unterwachtmeister – SS-Polizei-Regiment 19

Polizei-Unterwachtmeister” armed with a Beretta 1938 9mm Luger-caliber Italian machine pistol and 2 model 1924 hand grenades (Stielhandgranate 24).

He is dressed in a police uniform, covered with a German-made camouflage canvas tent of Italian origin (Telo mimetico m29).

It belonged to SS-Polizei-Regiment 19, temporarily attached to the 16.Volksgrenadier-Division from October 1944, and fought until mid-December 1944 in the Colmar Pocket, before moving to Slovenia to end the war there.

Created in 1942, this regiment was guilty of numerous exactions and war crimes during its anti-partisan operations in France and Slovenia.

This Luftwaffe division was created in December 1942 and took part in the Normandy battles, where it suffered heavy losses.

Disbanded in August 1944, its elements were scattered among several other units (21. Panzer-Division and 16. Infanterie-Division before becoming 16. Volksgrenadier-Division).

MG Schutze 1 – 16.Luftwaffen-Feld-Division

First MG Shooter “MG Schutze 1” armed with a 7.92X57mm MG.34 machine gun mounted on a Lafette 34-type heavy carriage, a Belgian GP.35 9mm Luger automatic pistol and a model 39 “egg” grenade (Eierhandgranate 39).

He is dressed in a camouflage blouse typical of Luftwaffe ground combat units, worn over his woolen uniform.

On his belt, he carries a maintenance kit for his machine gun, as well as a holster for his pistol. A common practice in the German army, he wears a band of cartridges around his neck.

He belongs to a unit of the 16 Luftwaffen-Feld-Division, amalgamated into the 16 Volksgrenadier-Division in October 1944.

This Luftwaffe division was created in December 1942 and took part in the Normandy battles, where it suffered heavy losses.

Disbanded in August 1944, its elements were scattered among several other units (21. Panzer-Division and 16. Infanterie-Division before becoming 16. Volksgrenadier-Division).

Grenadier – 716.Infanterie-Division

Grenadier armed with an RPzB.43 (Raketen Panzerbüchse 43, 8.8cm-caliber anti-tank rocket launcher known as a “Panzerschreck”) and a P.08 9mm Luger automatic pistol.

He is dressed in a winter outfit consisting of a woollen capote and reversible, early-made quilted pants (green and white side) worn over his uniform.

At his feet is a carrying case for two 8.8cm rockets (there are two types of ammunition, differentiated by a cross: use between -5°/+50° or a circle: use between -40° and +20°).

It belongs to an infantry unit of the 716 Infantry-Division created on May 2, 1941 and positioned in the Manche sector.

The division was engaged against British forces in June 1944 at Caen during the Allied landings. In August 1944, the division was in the south of France; following the Provence landings on August 15, it withdrew to the north-east before taking part in the fighting in the Vosges from October to November 1944.

In the same month, it amalgamated the remnants of various units before being engaged in the Poche de Colmar.