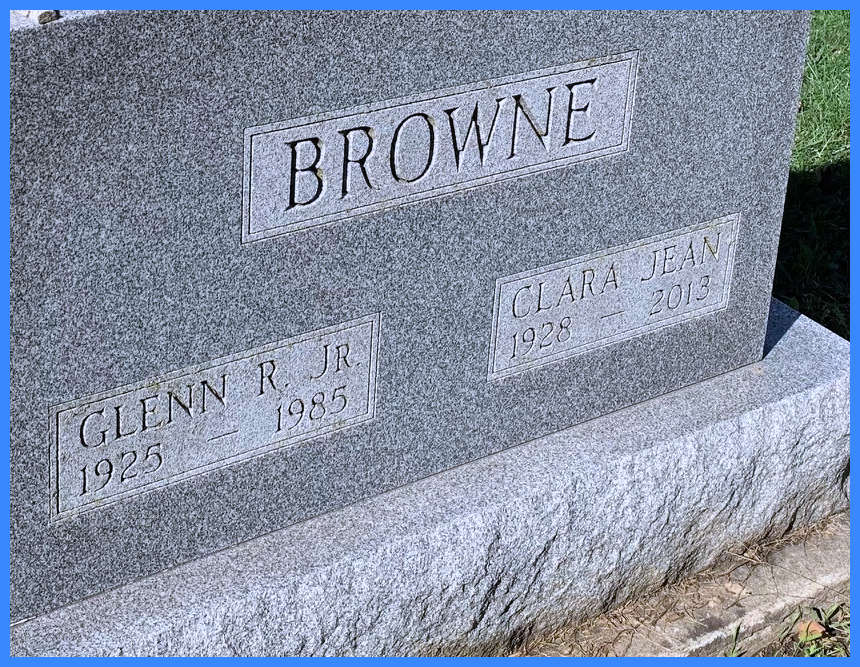

Glenn Reginald BROWNE Jr. 1925 – 1985

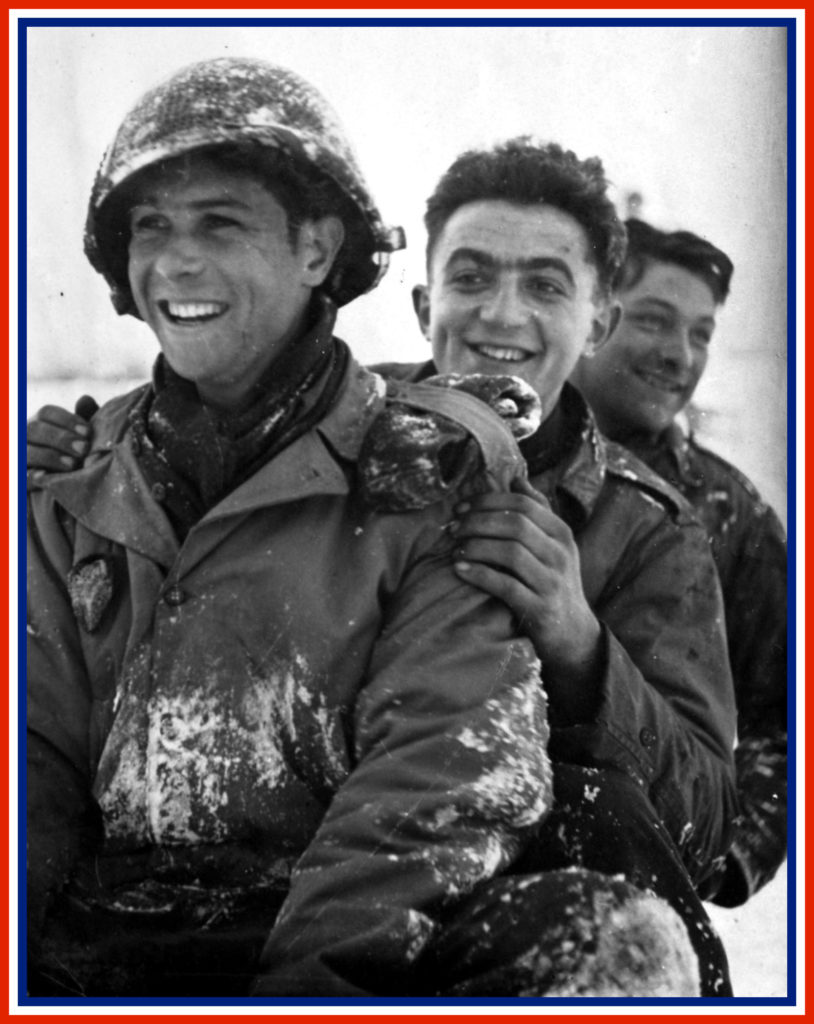

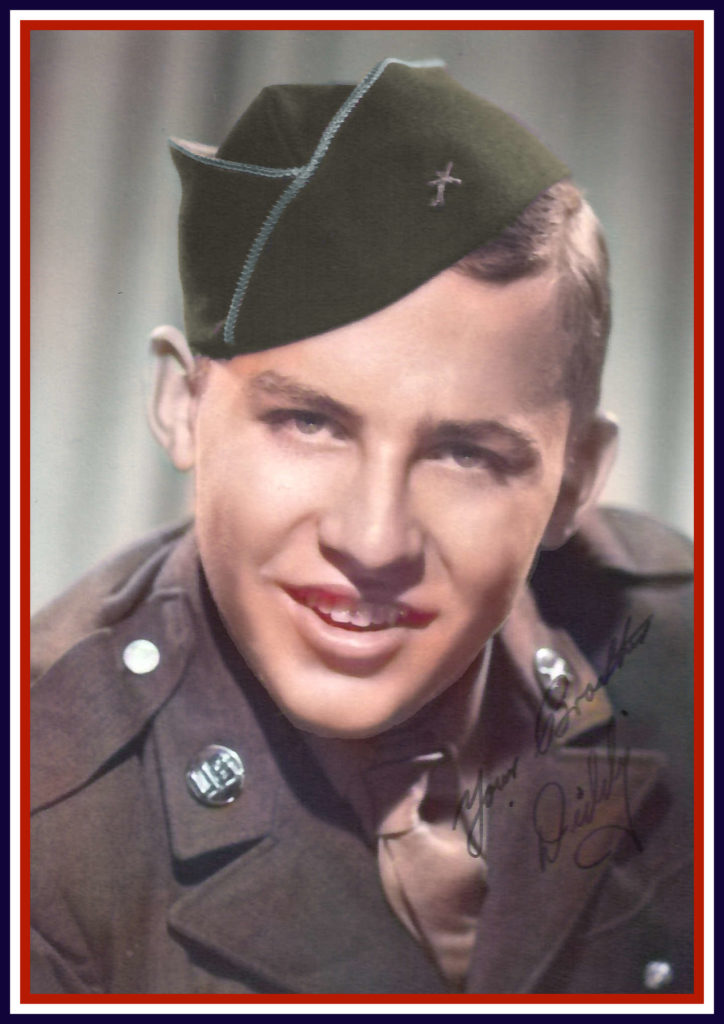

Glenn R. Browne Jr. was born September 15, 1925 in Hoopeston, Illinois the son of Glenn R. and Forrest Murray Browne.

His father was a veterinarian and served in that capacity in The Great War (World War I). He had an older brother Samuel Prescott Browne who was born in 1924.

Located in Vermillion Country, Hoopeston proudly called itself “The Sweet Corn Capital of the World”. Located approximately 100 miles south of Chicago, it was primarily a farming community, but it included several canning companies.

After the war broke out Browne wanted to enlist, but his parents would not allow it until he finished high school. He joined the army in 1943.

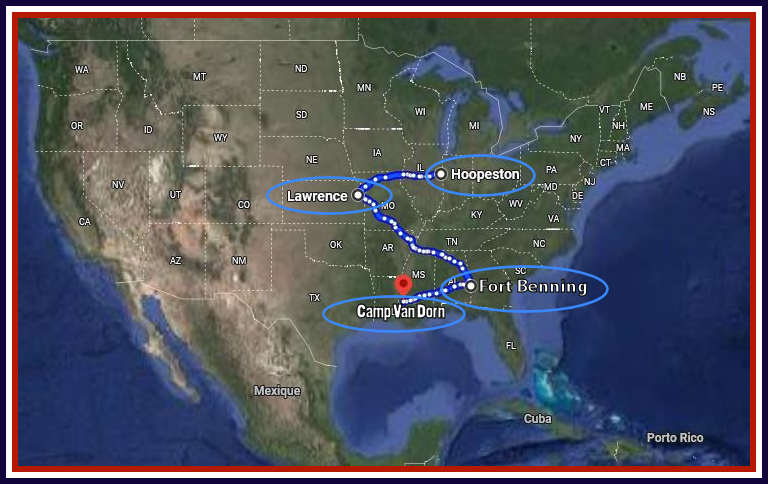

First, he was sent to Kansas University in Lawrence and enrolled in the Army Specialized Training Reserve Program (ASTRP) but that program was soon terminated.

Consequently, he did his basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia and further training at Camp Van Dorn, Mississippi.

He was promoted to Pfc. in September,1944 and then to instrument corporal before being sent to Europe in December 1944.

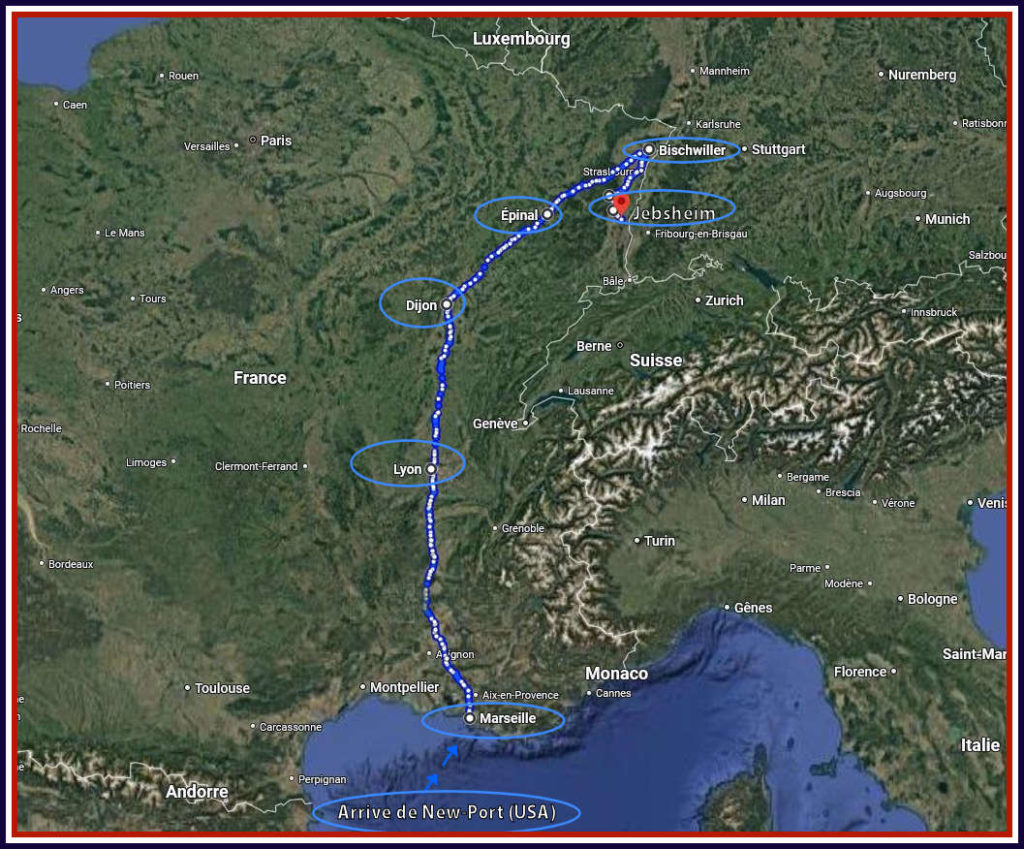

He entered France through the port of Marseille.

Browne was in the 2nd Battalion of the 254 Infantry in the 63rd Division ”the Blood and Fire Division”.

He ended up as a number one gunner in a heavy machine platoon with duties that included carrying the tripod of a 30-caliber machine gun.

During the Colmar campaign the 63rd was attached to the more well-known 3rd Division, First French Army, VI Army Group.

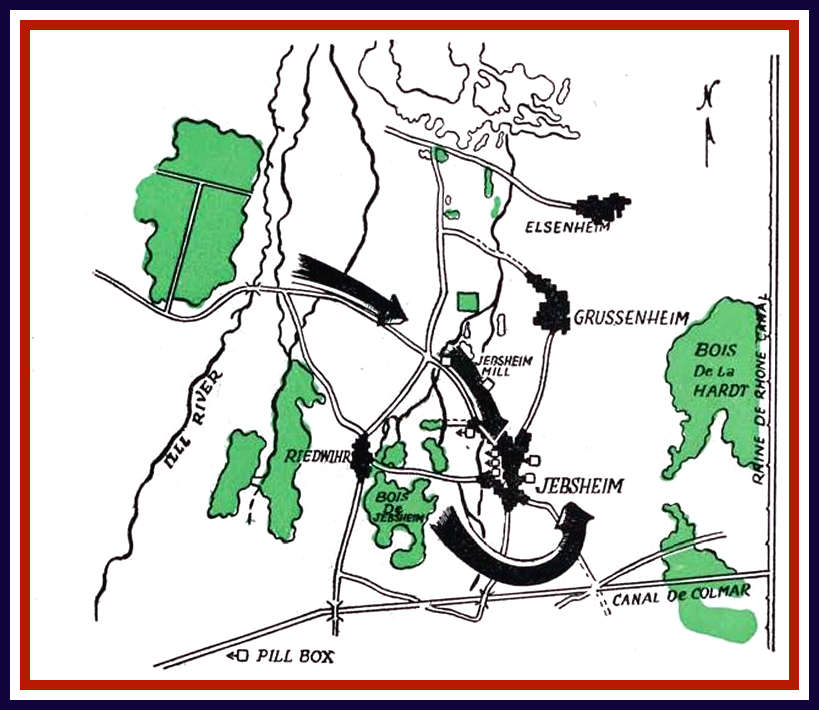

Browne’s battalion was responsible for the capturing the town of Jebsheim in January,1945.

Later in a short account about his experiences in the war, Browne mentions that he killed a German soldier while on sentry duty in Jebsheim.

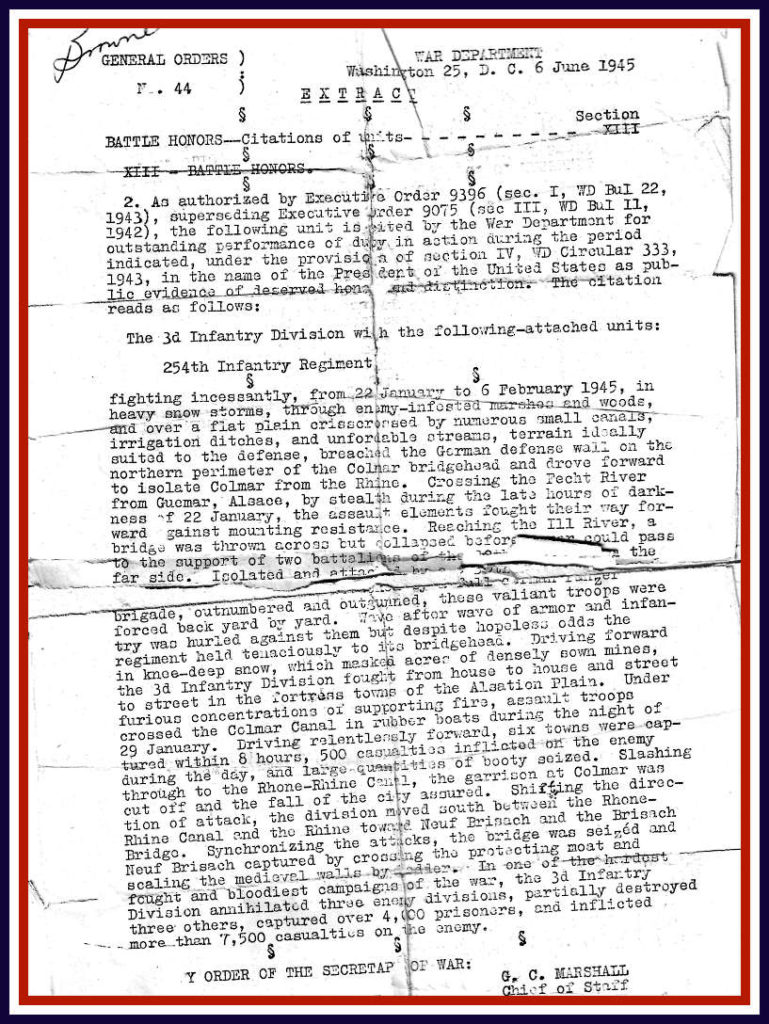

The action around Jebsheim earned the 254th a Unit Citation as described in detail here:

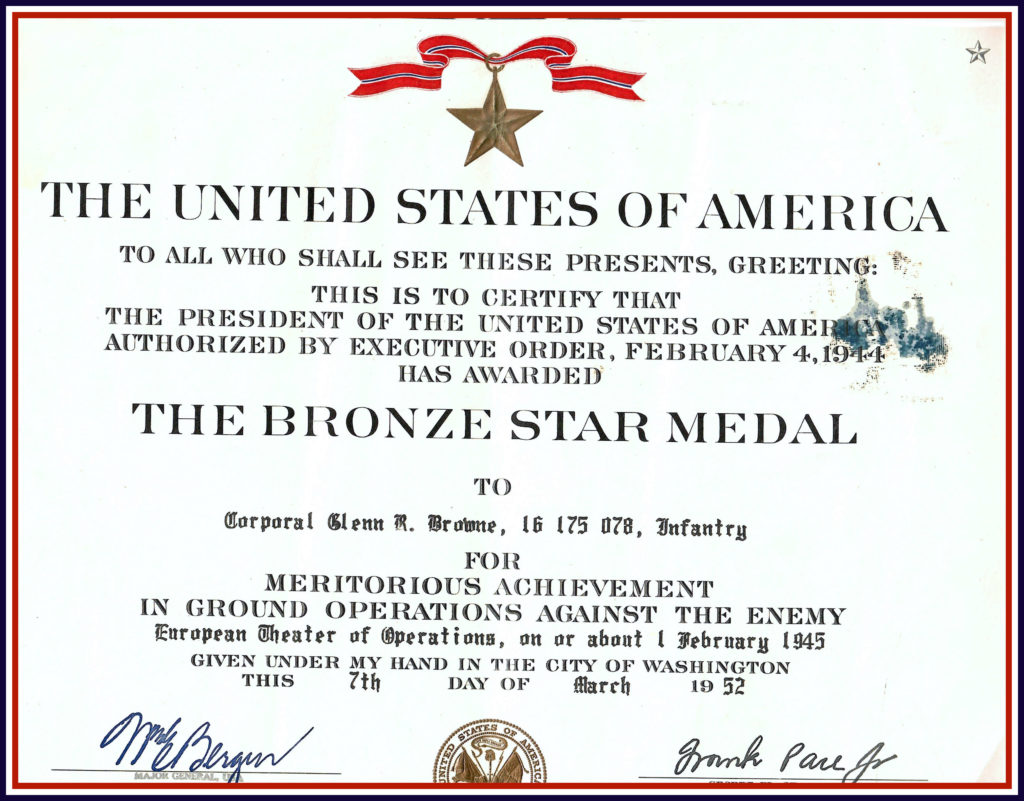

Corporal Glenn R. Browne was awarded a Bronze Star Medal for his service in the campaign.

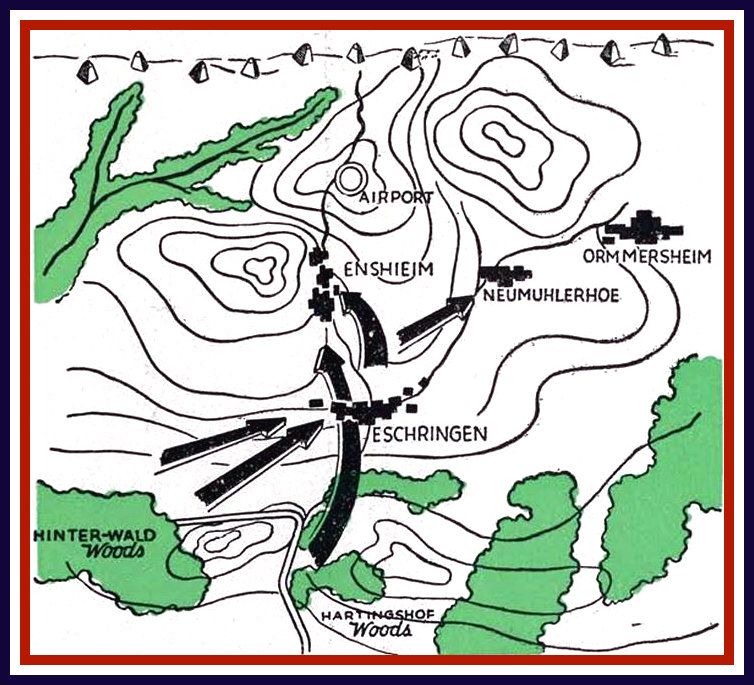

On April 25, 1944, as the war was winding down, Browne wrote a long four-page letter to his parents, which may have never been mailed, but it describes an attack on the town of Ensheim near the Siegfried line on March 17, 1944.

It included a map and the details of being under bombardment. A scanned copy of the letter is on the Browne Bio Source page.

Before V-E day, Browne spent time in the hospital with pneumonia and then prepared to be transferred to the Pacific Theatre when the war ended. He was discharged on February 8, 1946.

After returning to Hoopeston after the war, Browne enrolled at The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina in Charleston, South Carolina following in the footsteps of his older brother Sam.

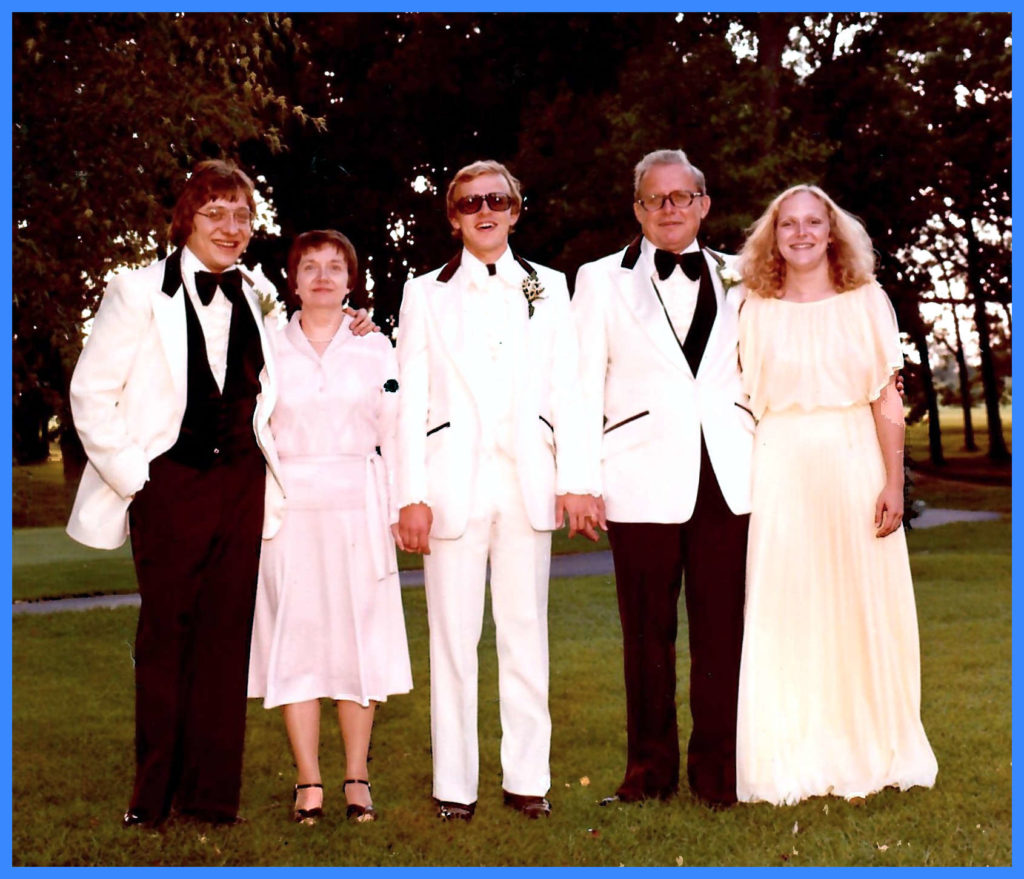

After graduated with a degree in Business Administration at the Citadel, he took a position as the Treasurer at the Milford Canning Company, in nearby Milford, Illinois. Glenn R. Browne Jr. married Clara Jean Burtis of Hoopeston, Illinois on January 7 1951, in Earl Park, Indiana at the home the bride’s brother-in-law and sister.

The couple had three children while residing in Hoopeston.

Neil was born in 1952; Murray was born in 1955 and Kay was born in 1958. Browne took two years of night courses and commuted to Chicago before graduating with a Master of Business Administration from the University of Chicago.

In 1960, the family built a house on a two-acre plot just outside of the village of Milford and Browne remained at the Milford Canning Company for his entire professional career at the Milford Canning Company before retiring for health reasons in 1984.

Final Years…

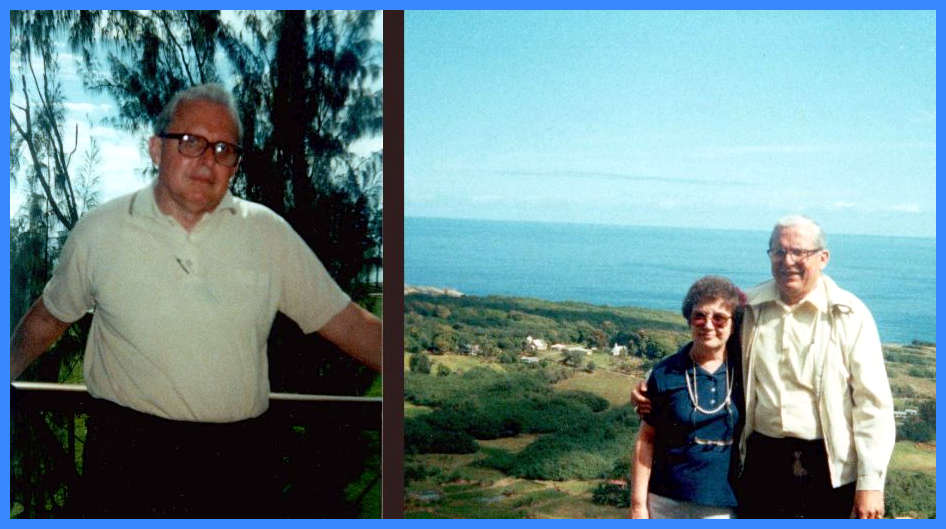

Glenn R. Browne was diagnosed with leukemia in the winter of 1983-84. He went into remission in the summer of 1984 and in fall 0f 1984 he retired with full pension. During his stay at the Carle Clinic in Champaign Jean stayed with him every night. In early 1985, Glenn and Jean went with their best friends to Hawaii.

Sadly, soon after they returned from the trip his cancer returned. Another round of chemotherapy weakened him to the point that he died on March 19, 1985 at the age of 59.

The funeral was held at the Brown-Alkire Funeral Home in Hoopeston and Glenn R. Browne was buried in the quiet Maple Grove Cemetery outside of Hoopeston.

Postscript…

In 2023, the only surviving family member Murray Browne wrote and published A Father’s Letters: Connecting Past to Present. In the short book, Browne examines the letters Glenn R. Browne wrote to his parents while he was in the service from basic training until he returned home. Most of these are letters short and written as V-Letters. In the 1970s and 1980s Browne also wrote hundreds of letters of his son Murray beginning while Murray was a young man in college and through the time of his untimely death. Upon retirement, Murray combed through the letters to revisit and to further understand his father.

In 2025, Murray brought two copies of his book to the Memorial Museum of Combat in Colmar and met with the museum curators who encouraged him to put together this exhibit.

For more information about this book, including availability visit the author’s website murraybrowne.org“

website : https://thebookshopper.typepad.com/blog/glenn-r-browne-jr-1925-1985.html

We sincerely thank Murray Browne for writing and sharing his father’s story so that we can pay tribute to him and his comrades in the 254th Infantry Regiment of the 63rd Infantry Division who participated in the liberation of our region.

We will never forget them!

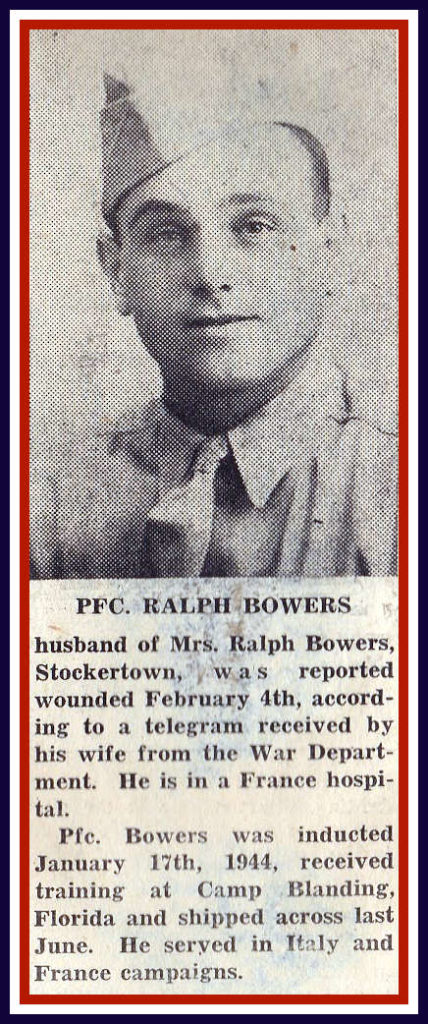

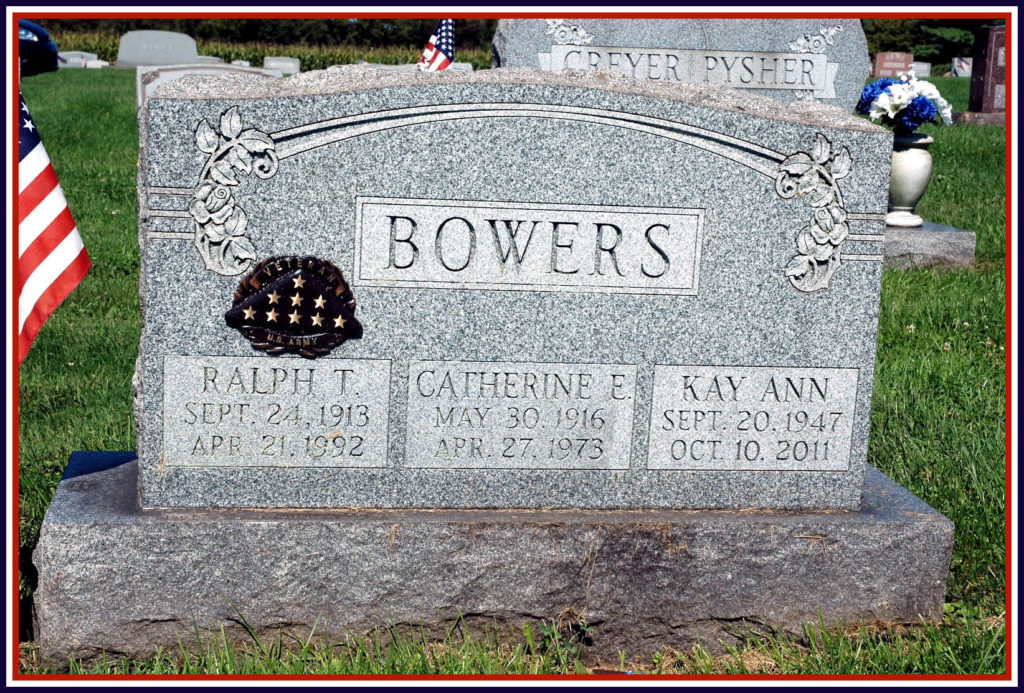

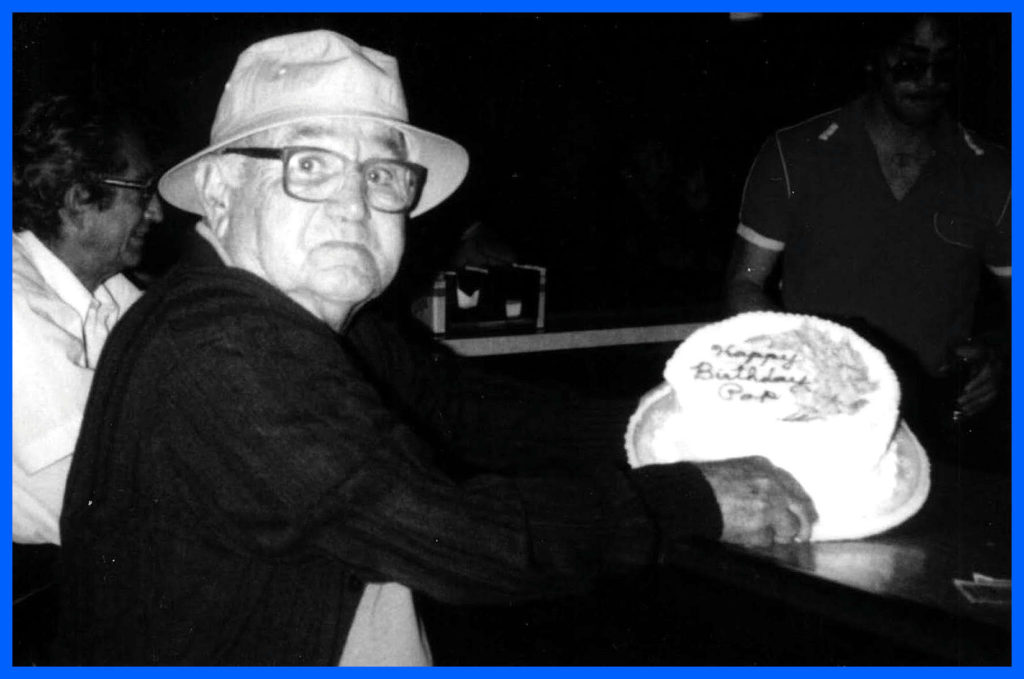

Ralph Thomas “Cork” BOWERS 1913 – 1992

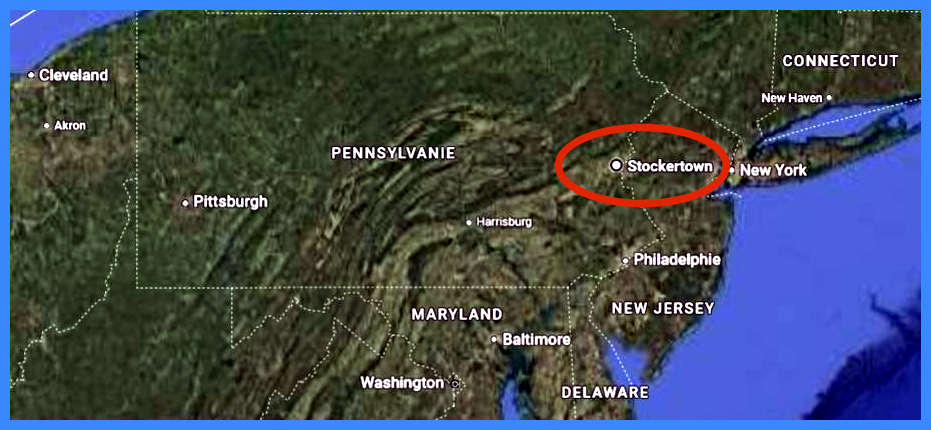

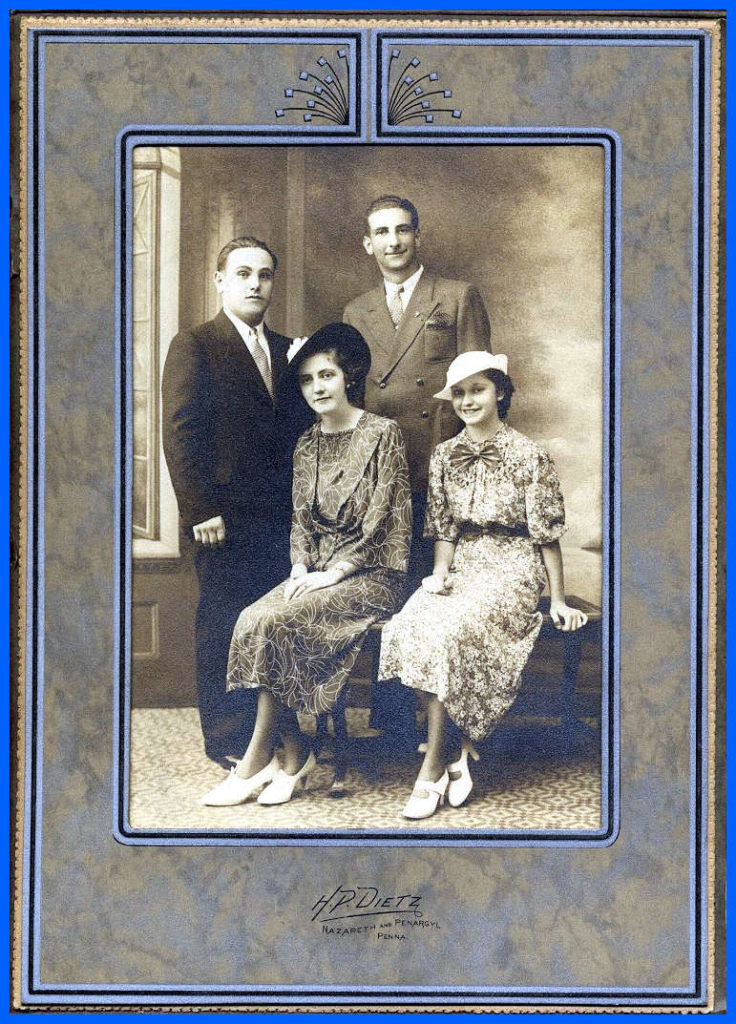

Ralph Thomas “Cork” Bowers was born on September 24, 1913 in Stockertown, Pennsylvania to Warren and Sarah Bowers.

His family emigrated from Germany in the 1700s and numerous members of the family fought to establish the United States of America during the Revolutionary War.

As was common in his era, he left school after 7th grade and helped support his family.

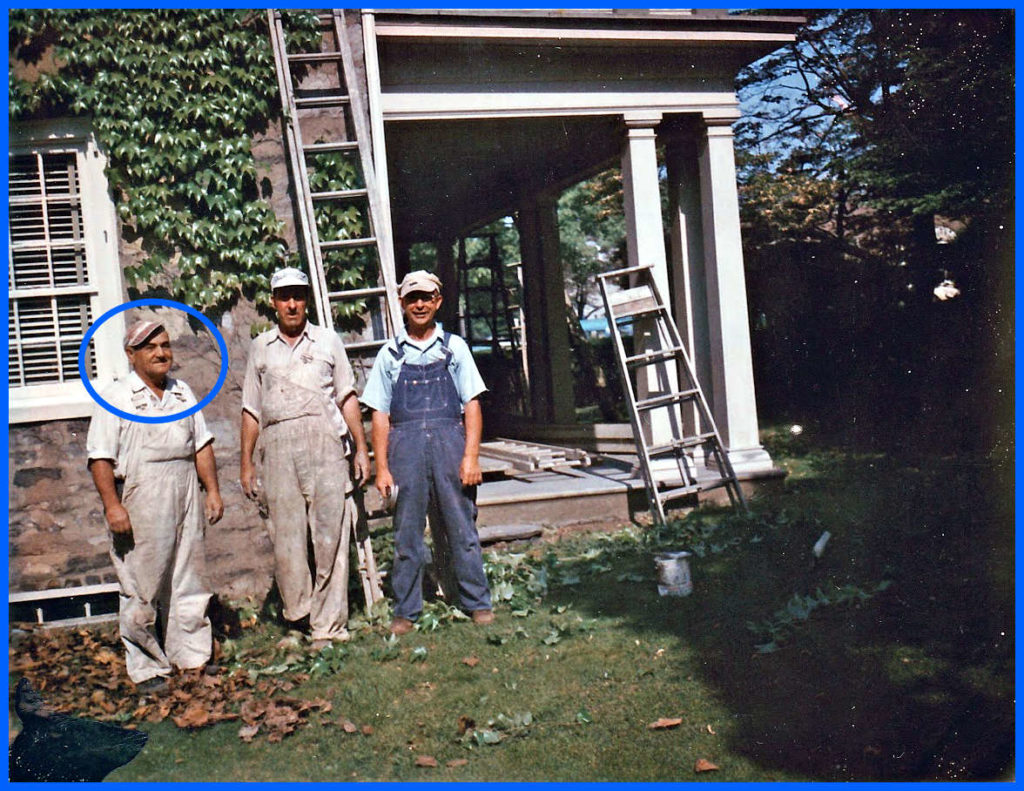

He worked in the silk mills and then as a painter and paper hanger with his family’s painting business.

On June 20, 1936, Cork married Catherine Elmira Marsch and in 1939, they welcomed their child in April 1939, Warren James “Corky” Bowers (and in 1947 a daughter Kay Ann).

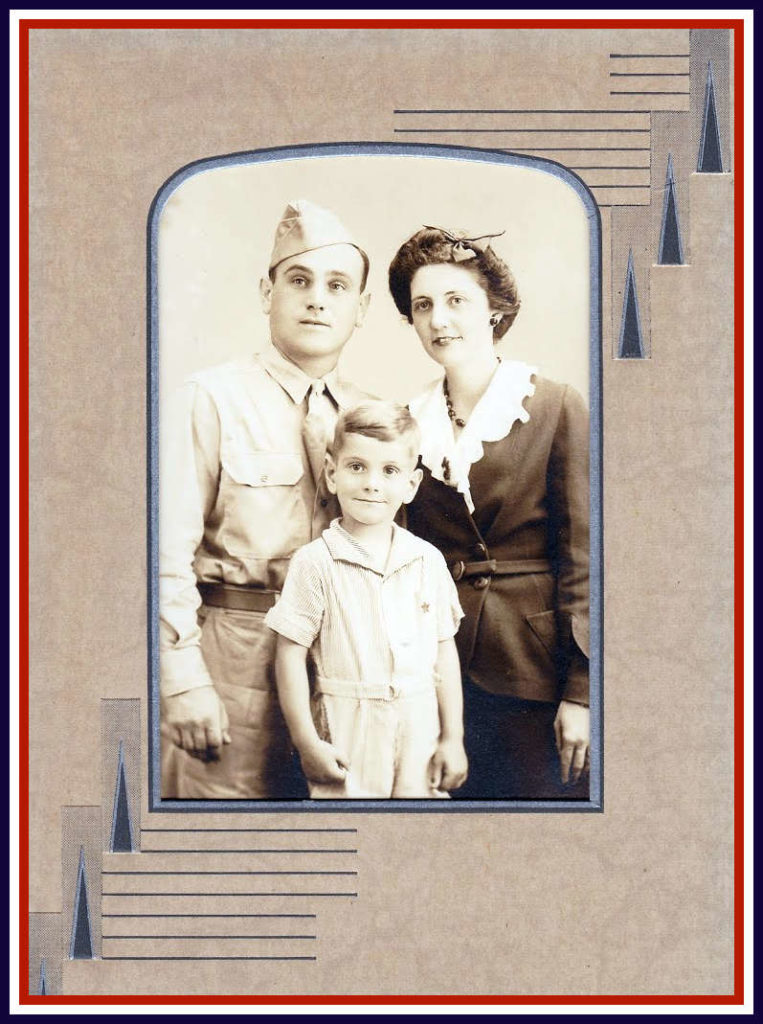

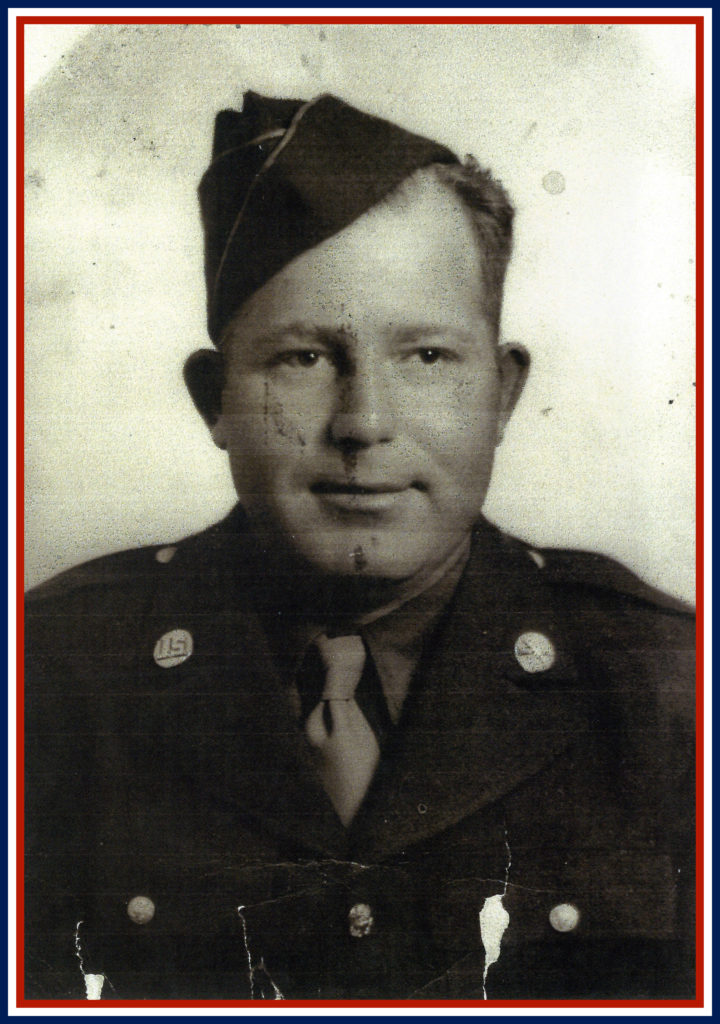

Despite having a wife and 4-year old son, he was drafted for service in 1943 and was inducted into the US. Army two days after Christmas, December 27, 1943.

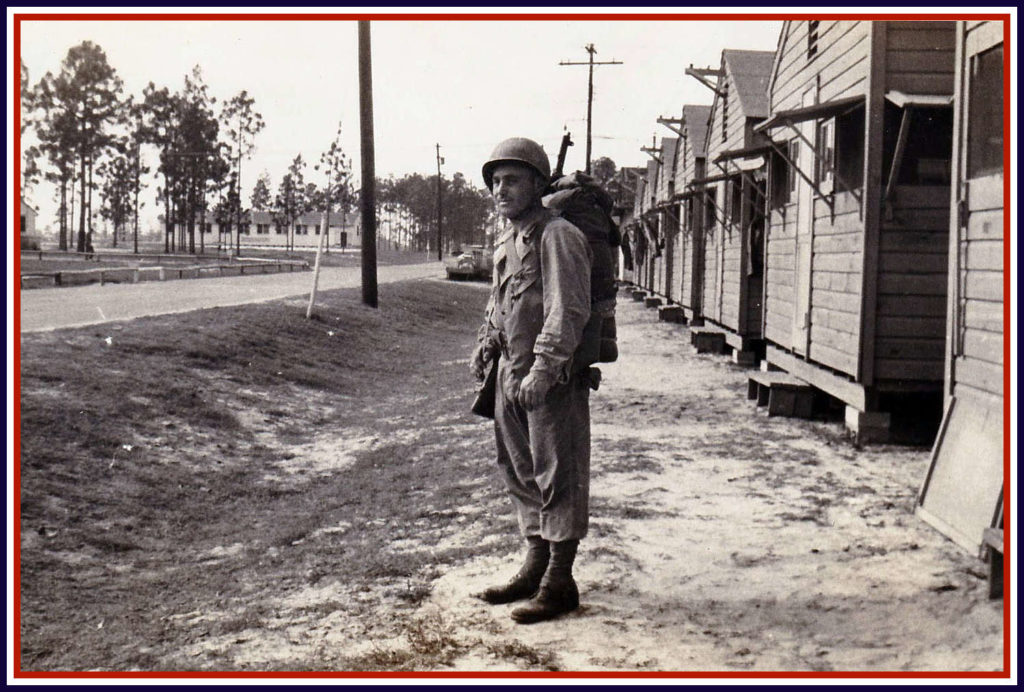

He trained in Camp Blanding, Florida as an Infantry Scout and shipped out for the European Theater of Operations on July 1, 1944 to arrive in Italy.

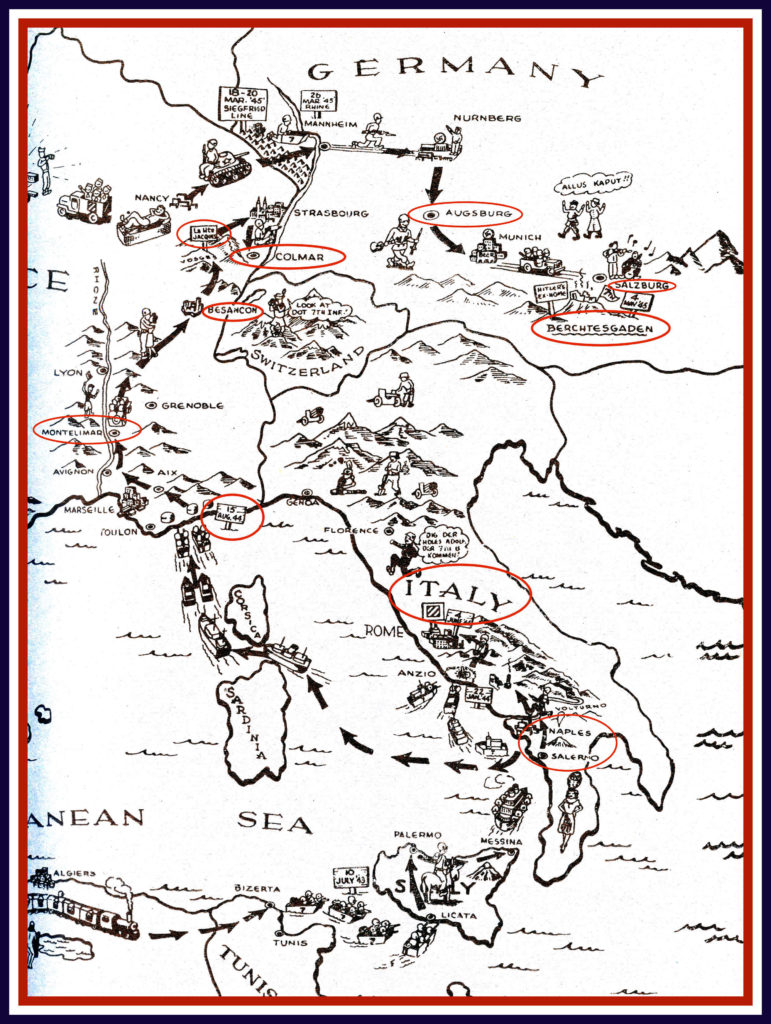

He served with the 7th Infantry Regiment(7th I.R.) of the 3rd Infantry Division.

The 7th IR. is known as “The Cottonbalers” regiment, so named from its use of cotton bales as defensive works during the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812.

Their regiment motto, “Volens et Potens” means Willing and Able.

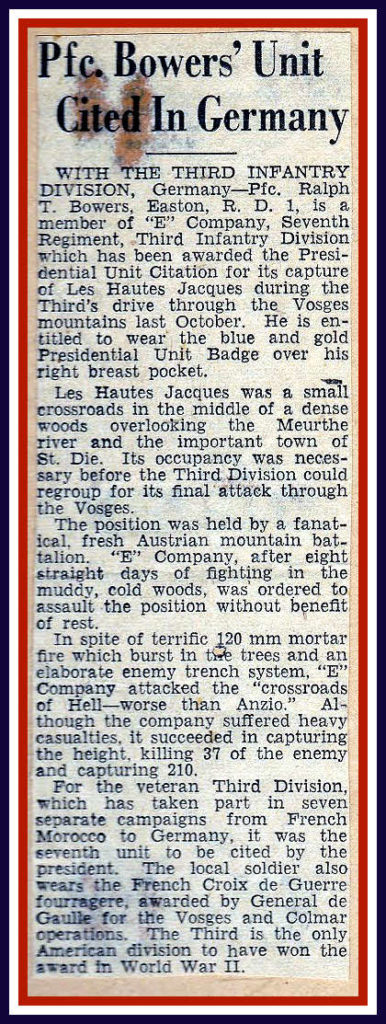

From Italy, his unit participated in the invasion and campaign of southern France, through the Vosges Mountains where Ralph and company E distinguished themselves from October 30 to November 4, 1944, during the “Haute Jacques” battles…

…and fought through the brutal winter in “the forgotten battle” of the Colmar Pocket campaign.

It was just outside of Ostheim, on the 23rd of January 1945 where he earned the Silver Star medal for Gallantry in Action.

His Citation:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star Medal to Ralph T. Bowers (33835800), Private First Class, U.S. Army, for gallantry in action while serving with Company E, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3d Infantry Division. On 23 January 1945, near Ostheim, France, Private First Class Bowers single-handedly attacked an enemy machine gun which had killed 1 soldier, wounded 10 more, and forced the other members of his platoon to seek cover in a ditch. Although bullets skimmed over his head, he crawled to a point 35 yards from the enemy, and loaded his bazooka. Then, rising to his knee, he fired one round into the hostile gun emplacement, killing the gunner and wounding his assistant. With the enemy weapon silenced, his platoon was able to resume its advance. Headquarters, 3d Infantry Division, General Orders No. 223 (June 23,1945) Home Town: Easton, Pennsylvania.

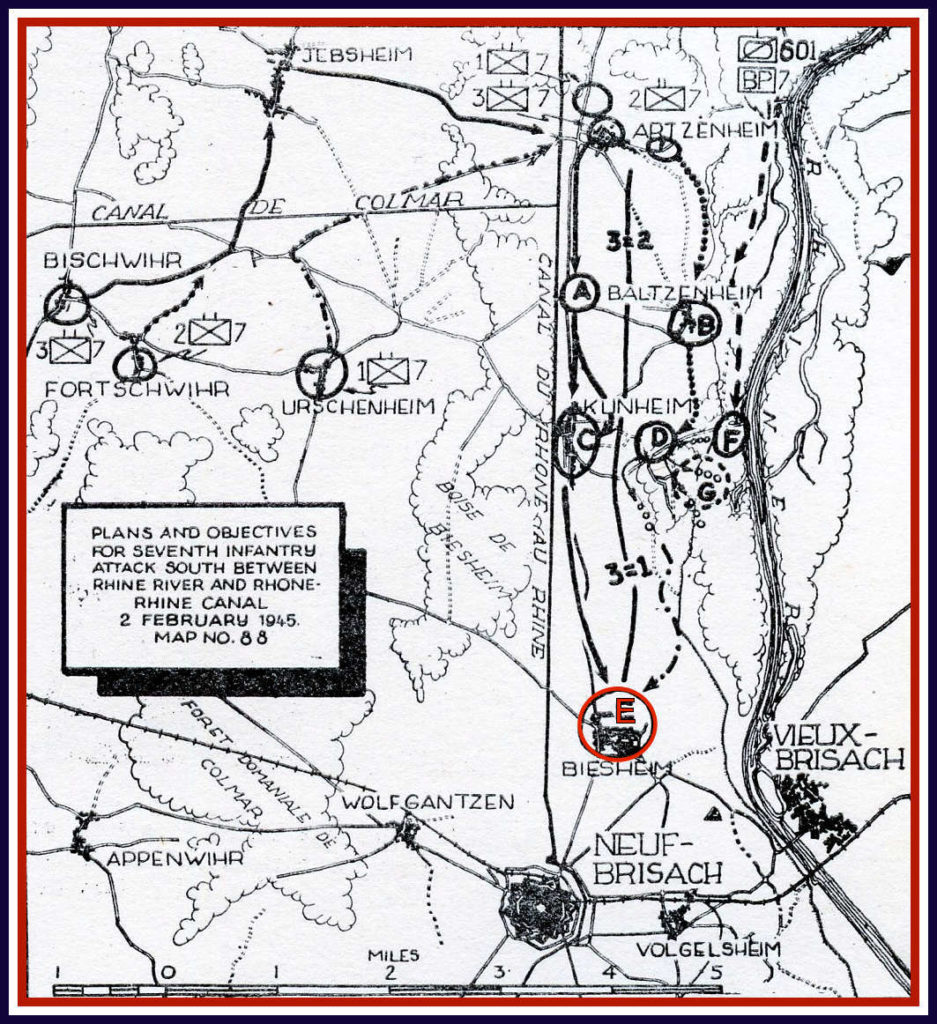

He was wounded during fierce fighting on February 4, 1945 (we assume near Biesheim – his records were part of the records lost in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center) and was hospitalized for several weeks ending up in a hospital in Paris.

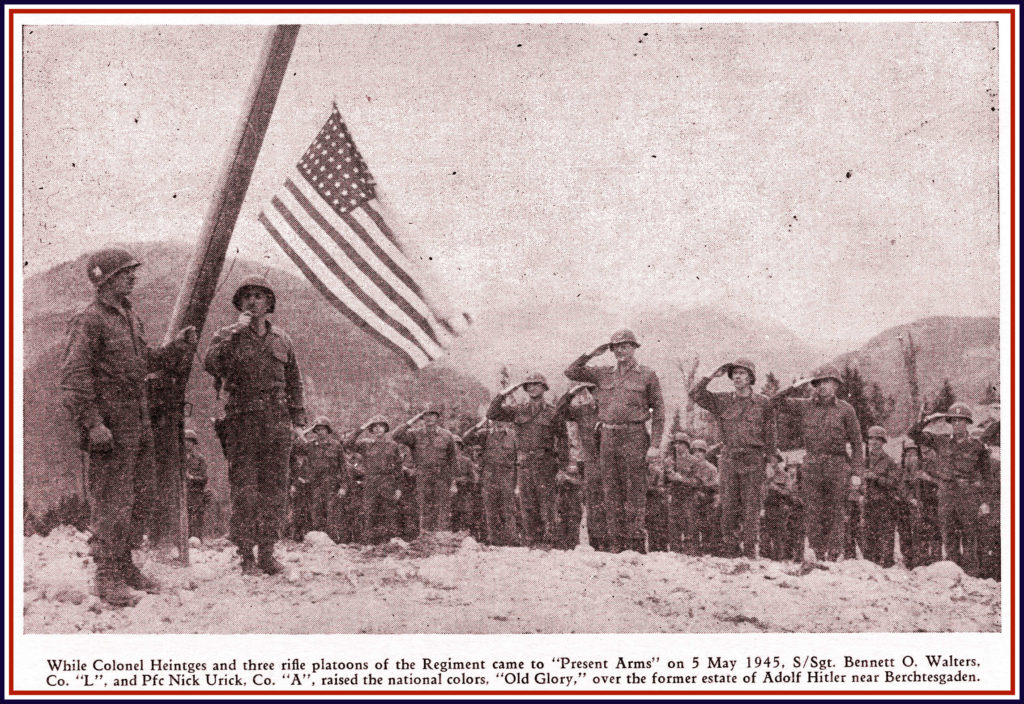

By mid-March, he was back with his unit and crossing into Germany, breaking through the Siegfried line and fighting onward to be with the first Allied troops into Berchtesgaden on May 4, 1945.

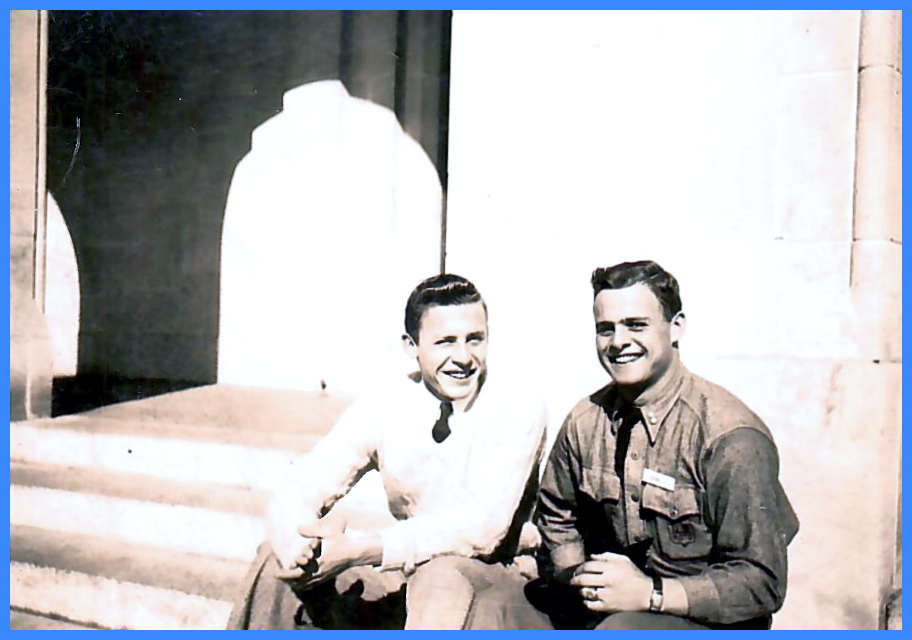

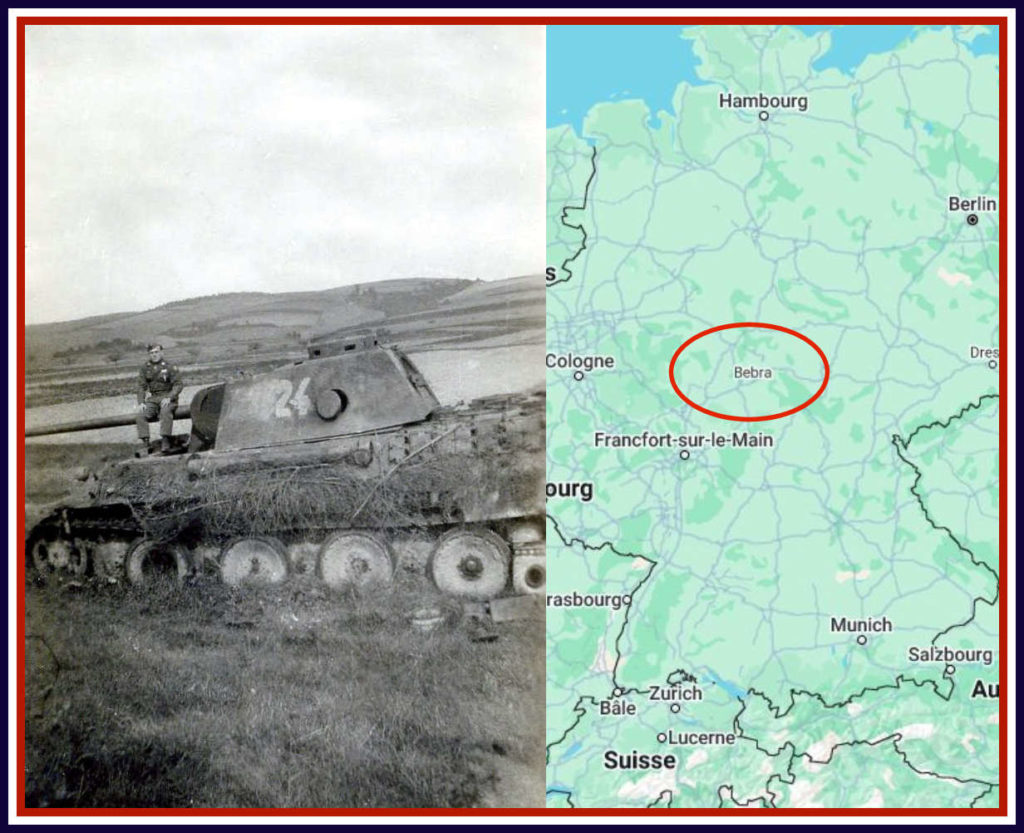

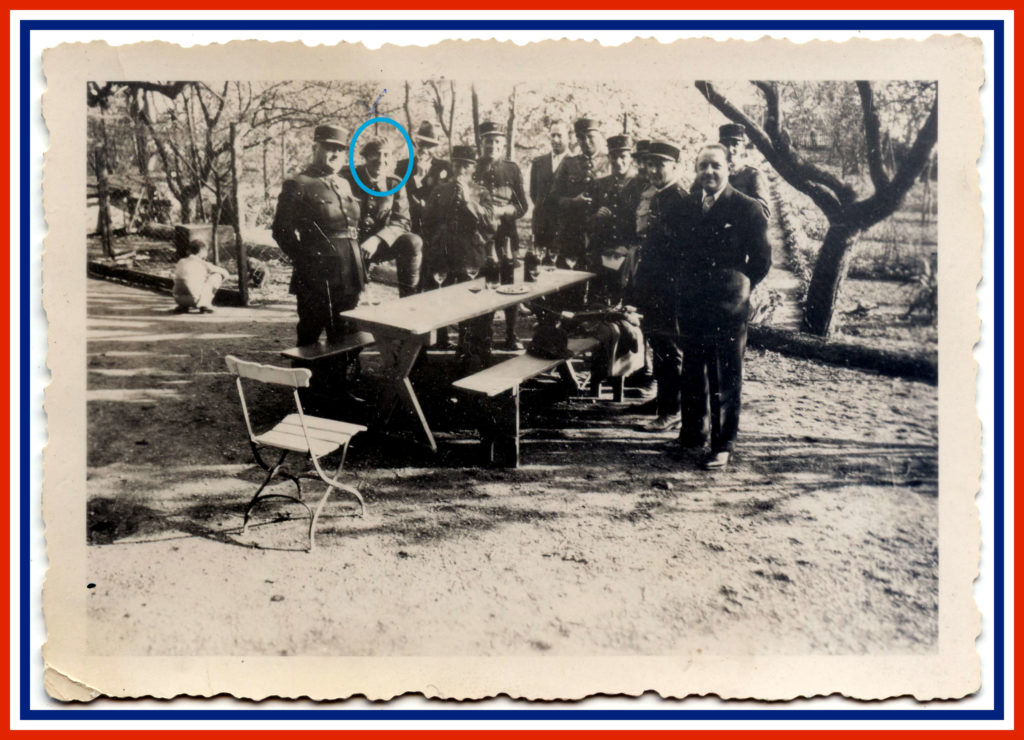

Photo most likely taken after May 8, 1945, during the German occupation, in Bebra near Kassel.

Ralph Thomas “Cork” BOWERS’ unfailing commitment to the Second World War is reflected in the 3 medals he earned for his bravery in combat : 1 Silver Star, 1 Bronze Star, 1 Purple Heart.

He returned to Pennsylvania in December of 1945 having completed his military service.

He rejoined the family painting and paper hanging business and in 1947, his wife gave birth to their daughter Kay Ann.

He never wanted to talk about his time in the service and when anyone would suggest that he was a hero, he would disagree and said that he just did what had to be done. As his granddaughter, I still think he was pretty heroic!

Despite having frequent nightmares and persisting pain from his wounds for the rest of his life he worked hard every day to support his family the best way that he could.

He also served as the volunteer Fire Chief in his home town.

He passed away April 21, 1992 at the age of 78, having outlived his wife, Catherine by 19 years.

He was buried with military honors with shrapnel still in his body.

When times feel like they are getting difficult, I remind myself of the actions that my grandfather took in the service of his country, and for the sake of freedom across the globe and I realize that the situation isn’t that bleak and that I should just try to BE LIKE RALPH! I have a framed reminder that I keep on my desk to Be Ralph.

Written by Jill Bowers, granddaughter of Ralph T. “Cork” Bowers

We sincerely thank Jill Bowers for sharing her family archives and her story so that we can pay tribute to Ralph Thomas “Cork” BOWERS for his engagement and participation in the liberation of our region from the Nazi yoke.

We won’t forget Ralph and his comrades!

Joseph Louis BALE III 1924 – 1945

Originaire du comté de Wayne, dans le Michigan, il est né à Detroit le14 janvier 1924.

Il est le fils de Maurice Isaac Bale (1900-1965) et Edith Mary Pearlman (1901-1989). Il est surnommé « Little Jœ », contrairement à un autre membre de sa famille qui porte le même prénom et qui est lui surnommé « Big Jœ ». Joseph L. Bale (célèbre dans le comté pour ses aptitudes sportives, et apparaissant régulièrement en tête d’équipe lors des championnats de baseball, de cross-country et de basketball).

Joseph L. Bale prépare son entrée au Michigan State College, lorsqu’éclate la deuxième guerre mondiale. Il est alors enrôlé dans l’armée américaine et rejoint les effectifs de la 3rd Infrantry Division, où il effectue sa formation initiale.

Après ses classes, Le Private First Class (Pfc.) Joseph Louis Bale III, numéro de matricule 16105122, est affecté à l’Etat-major du second bataillon (Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion) du 7th Infantry Regiment de la 3rd Infantry Division, de la Seventh U.S. Army. Le surnom donné aux soldats du 7th Infantry est “Cottonbalers” et leur devise « Volens et Potens » qui veut dire « Volonté et capacité » (Willing and Able).

Joseph participe aux débarquements d’Anzio en Italie et celui de Provence en France. Il effectue la longue remontée, des troupes alliées du sud de la France vers l’Alsace. Il est blessé à trois reprises au cours de son service actif et réintègre à chaque fois son unité à l’issue de ses convalescences successives.

Au moment du déclenchement de l’opération « Krautbuster » c’est à dire le franchissement du canal de Colmar, puis la prise des localités de Wihr-en-Plaine et de Horbourg ; Le Pfc. Joseph L. Bale qui appartient à la compagnie d’état-major du 2nd Battalion du 7th Infantry Regiment est sous les ordres du Major Duncan.

Dans la nuit du 29 au 30 janvier 1945, alors que le 2nd Battalion vient de franchir le canal de Colmar et approche de Wihr-en-Plaine, les soldats américains se heurtent à deux chasseurs de chars « Jagdpanther » allemands. Ces derniers dispersent les fantassins américains par des tirs d’obus explosifs et de mitrailleuses, qui occasionnent des pertes notables, bousculent les Companies F et G et frappent de plein fouet la Company E qui se trouve en réserve, ainsi que le groupe d’état-major du bataillon.

Le Major Duncan appelle alors en renfort les équipes anti-char armés de bazookas, afin d’engager les blindés lourds allemands. Le Pfc. Joseph L. Bale, qui fait parti de l’une de ses équipes anti-char, se tourne alors vers le Major Duncan et lui dit : « Eh bien, Monsieur, nous voici au dernier round ! » Le jeu de mots en anglo-saxon (round = roquette/munition) est bien choisi car il n’a en effet plus qu’une roquette.

Le tir n’est pas aisé vu la distance à laquelle il se trouve par rapport au Jagdpanther (estimation à plus de 500 yards, soit 457 mètres) qui est très au-delà de la portée utile du bazooka (maximum 300 yards/270 mètres). Les soldats présents autour de Bale retiennent leur souffle… « J’avais l’impression que des années passèrent » se remémore plus tard le Major Duncan.

Le soldat Earl A. Reitan indique dans son livre autobiographique : « La roquette décrivit un arc et frappa le char, qui explosa et prit feu. L’équipage allemand sauta du blindé en flammes. Les hommes se roulèrent dans Ia neige pour éteindre le feu qui brulait leurs uniformes. Un second char leur vint en aide, récupéra les survivants et se replia. Une grande clameur vint de la compagnie E. J’entendis cette clameur et escaladais le mur, mais ne vis pas le tir miraculeux […]. »

Le Major Duncan notait les mêmes scènes de liesse parmi ses hommes : « Les soldats ne purent se réfréner. Ils hurlaient à pleins poumons. Certains pleuraient de joie sans retenue. »

Certains soldats américains voulurent ouvrir le feu sur l’équipage du Jagdpanther, mais ne disposant plus de roquettes de bazooka, ils jugèrent préférable de ne pas attirer l’attention sur eux.

Le blindé allemand détruit est à priori le Jagdpanther numéro 311 commandé par l’Unteroffizier Hüsing. Deux membres d’équipage sont tués dont Hüsing lui-même, probablement morts brûlés vifs dans le blindé. Les trois autres membres d’équipage du char sont blessés (dont le tireur Roth). Le second Jagdpanther, après avoir récupéré les survivants de l’équipage, se replie dans le village.

Plus tard, dans la matinée du 30 janvier 1945, les forces allemandes déclenchent une violente contre-attaque qui vise à reprendre Wihr-en-Plaine. Celle-ci est appuyée par le Jagdpanther rescapé de l’accrochage précédent, aux abords du village. Le Major Duncan ordonne alors à ses hommes de se mettre à couvert dans les bâtiments, puis demande un tir de soutien d’artillerie sur la localité pour stopper l’offensive allemande.

C’est à ce moment-là que le Pfc. Joseph L. Bale, auteur du tir « miraculeux » au bazooka, tente de détruire le second blindé allemand. Réapprovisionné en roquettes, il tir depuis l’intérieur du bâtiment où il se trouve. Afin d’accélérer sa cadence de tir, Bale veut charger lui-même son bazooka, ce qui est normalement la tâche du pourvoyeur. Alors qu’il veut insérer la roquette dans le tube de son bazooka, cette dernière lui glisse des mains qui sont engourdies par le froid, et explose au contact du sol : elle lui arrache les deux jambes ! Il meurt peu de temps après des suites de ses blessures. Dix-sept autres de ses camarades qui se trouvent à proximité sont également blessés ou commotionnés par cette explosion.

Pour son action on lui décerne à titre posthume, l’une des décorations les plus prestigieuses de l’armée américaine, à savoir la Distinguished Service Cross, ainsi que la Purple Heart (médaille des blessés) avec trois feuilles de chêne (3 fois blessés).

La citation présidentielle qui accompagne la remise de la Distinguished Service Cross est la suivante :

« Le Président des Etats-Unis d’Amérique, autorisé par Acte du Congrès du 9 juillet 1918, est fier de décerner la Distinguished Service Cross (à titre posthume) au soldat de première classe Joseph L. Bale (matricule : 16105122), de l’Armée des Etats-Unis, pour son extraordinaire héroïsme en lien avec des opérations militaires contre un ennemi armé durant son temps de service au 2e Bataillon du 7e Régiment d’Infanterie de la 3e Division d’Infanterie, au combat contre les troupes ennemies le 30 janvier 1945 à proximité de Wihr-en-Plaine, France.

Ce jour-là, le bataillon du soldat Bale fut attaqué et stoppé par des blindés ennemis qui écrasèrent plusieurs fusiliers, en tuant un grand nombre.

Sous les tirs de 88 mm, d’armes automatiques et de grenades à fusil, le soldat de première classe Joseph L. Bale attaque sans crainte avec son lance-roquettes, ignorant les obus qui explosaient à cinq yards alentours et les balles d’armes automatiques qui martelaient la position. Il mit hors de combat un blindé ennemi, obligeant les Allemands à battre en retraite. Plus tard dans la même matinée, alors que son bataillon était attaqué par un autre blindé à une centaine de yards de distance, il brava un tir d’artillerie en tentant à lui seul de détruire ce dernier, mais fut mortellement blessé.

Les actions intrépides du soldat de première classe Bale, sa bravoure et le zèle dont il fit preuve dans son dévouement au prix de sa vie, illustrent les plus hautes traditions des forces armées des Etats-Unis et rayonnent à grand crédit sur lui-même, la 3e Division d’Infanterie et l’Armée des Etats-Unis. »

Le Pfc. Joseph L. Bale III repose en paix pour l’éternité au milieu de ses frères d’armes au cimetière militaire américain d’Epinal.

Sa tombe (n°56) se trouve dans le Carré B, dans la Rangée 34.

En Mémoire de son sacrifice ultime pour la libération de Wihr-en-plaine, nous lui rendons l’hommage qu’il mérite et ne l’oublierons jamais !

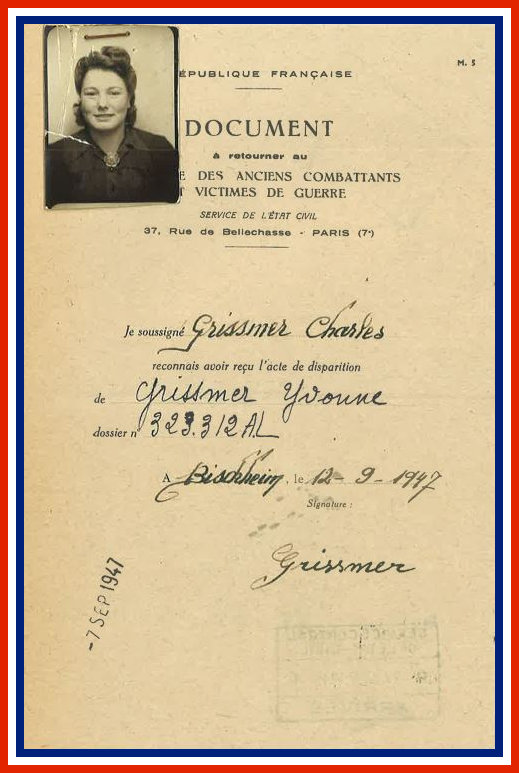

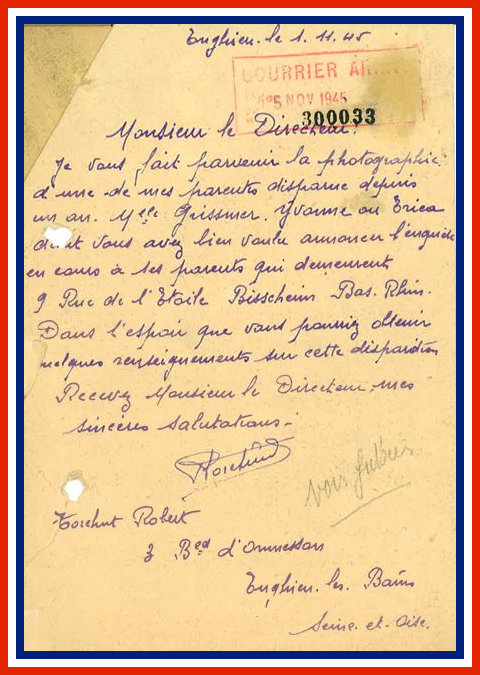

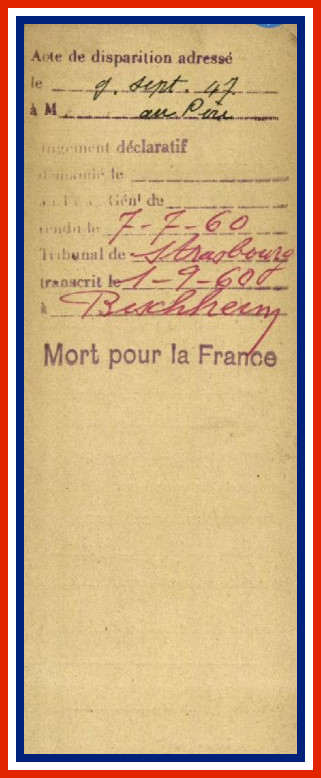

GRISSMER YVONNE 1925 – 1944

She was born on March 18, 1925 in Strasbourg (67) and grew up in the village of Bischheim (67), where her parents lived.

She is the daughter of Charles Grissmer and his wife Marie Kaufeld.

Single, she lived with her parents at 10 rue de l’étoile in Bischheim.

After the Nazi annexation of Alsace, she had to change her first name (Yvonne being “too French”) to Erika (as part of the forced Germanization of the Alsatian population, all French first names that had no equivalent in German had to be replaced by a Germanic first name from a list of pre-selected names).

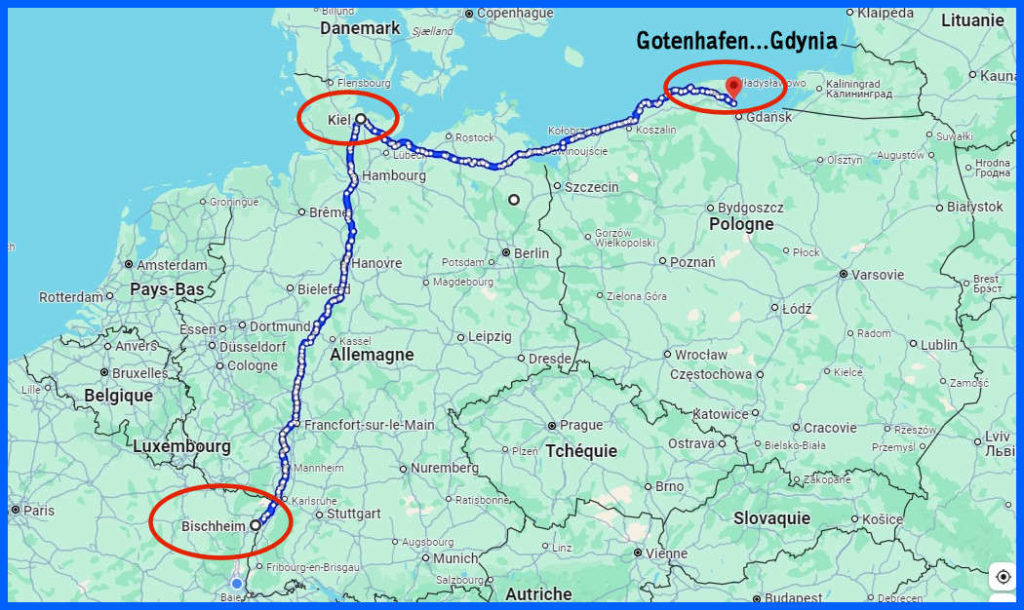

On May 5, 1944, she was drafted into the German navy, the Kriegsmarine, and sent as a Marinehelferin to Kiel, a major seaport on the Baltic Sea.

On November 20, 1944, she gives her last news to her parents from Osehhof-Gottenhafen in Poland, and not in Germany as indicated in the file (Gotenhafen = today’s town of Gdynia in Poland).

Her death certificate records the date of November 20, 1944… she was 19 years old.

She almost certainly sank with the ship she was on (during this period, many German ships were sunk by Allied aircraft or Russian submarines along the North Sea and Baltic coasts).

On March 29, 1960, in a statement made to the Schiltigheim gendarmerie (as part of the study of the files of those drafted by the French Ministry of Veterans Affairs), her father declared:

“My daughter Grissmer Yvonne was drafted into the German navy in 1944. Since the date of her departure, she has not returned to our home. Her last letter, dated November 20, 1944, was from Osehhof-Gottenhafen in Germany (Gotenhafen = today the town of Gdynia in Poland). I know that my child was on a boat. She was with a girl from Strasbourg-Robertsau whose name and address I don’t know. That’s all I can tell you about my daughter.

On the same day, the gendarmerie questioned two other witnesses:

Joseph Lehmann, 50, a painter who also lives at 10 rue de l’étoile in Bischheim, declares:

“Grissmer Yvonne was a neighbor. In 1944 she was drafted into the German army. I don’t know what became of her. In any case, she never returned to her father’s home. I can certify that this young girl did not volunteer to serve the German cause and that if she left, it was under duress”.

Charles Erb, 54, town clerk in Bischheim, who said:

“I knew the young Grissmer Yvonne well, who was born on March 18, 1925 in Strasbourg. She was drafted into the German navy in 1944. She never returned to the home of her parents, who live in our commune, at 10 rue de l’étoile. This family always had Francophile feelings”.

On July 7, 1960, the Strasbourg court awarded her the title “MORT POUR LA FRANCE” (“DEAD FOR FRANCE”).

Many thanks to Claude Herold for his research and for sharing the information and documents he found.

Source : dossier AC21P219193/323312AL du Service Historique de la Défense de Caen – Mémoire des Hommes.

Sanitäter de la 716.Infanterie-Division

This sub-officer, affiliated to a Sanitätskompanie (Sanitary Company), is responsible for providing first aid to his comrades on the battlefield.

He wears a chasuble and a red cross armband to identify his role as caregiver to soldiers in his division and to opposing forces.

He carries two 1-liter canteens for the wounded, as well as two leather saddlebags on his belt and a metal crate for carrying his first-aid supplies.

As in every Wehrmacht division, the organization of medical units was essential to ensure medical support for troops in the field.

These units were responsible for first aid, evacuation of the wounded and their initial treatment before any transfer to more distant field hospitals.

The general organization of these units is as follows:

1. Sanitätsdienst (Divisional Health Service)

Each Wehrmacht division has a Sanitätsdienst, headed by a Divisionsarzt (Divisional Medical Officer), a senior medical officer.

2. Sanitätskompanie (Sanitary Company)

Each division generally has two Sanitätskompanien, which are advanced care units responsible for :

Providing first aid to the wounded on the battlefield.

Set up advanced aid stations (Hauptverbandplätze) a few kilometers from the front.

organize evacuation of the wounded to rear medical facilities.

3. Krankenkraftwagenzüge (Ambulance sections)

These motorized units are equipped with Krankenkraftwagen (ambulances) to transport the wounded from aid stations to field hospitals or rail transfer points.

4. Feldlazarett (Field Hospital)

Located further back from the front for safety reasons, it is used to treat the seriously wounded and stabilize them before transfer to a permanent hospital.

Feldlazarett can be set up in tents or requisitioned buildings.

5. Krankensammelstellen (Casualty gathering points)

Areas where the lightly wounded can be rapidly treated and possibly returned to duty, while the seriously injured are sent to the rear.

6. Veterinärdienst (Veterinary Service)

Responsible for the care of horses, which are essential for transporting supplies, ammunition, etc. in the German army’s infantry and artillery units.

Includes a Tierarzt (military vet) and a Pferdelazarett (horse hospital).

Additional medical support

In addition to divisional medical units, evacuation hospitals (Evakuierungslazarette) and permanent military hospitals (Kriegslazarette) existed in the rear zone, often linked to rail networks for the evacuation of wounded to Germany.

This structure enabled the Wehrmacht to effectively manage the care of its wounded soldiers while maintaining its war effort.

References:

“Handbook on German Military Forces” (TM-E 30-451, published by the US War Department in 1945) – This detailed handbook describes the organization and structure of German medical units during the Second World War.

“Die deutsche Wehrmacht 1939-1945” by Wolfgang Fleischer – An analysis of the organization and functioning of the various branches of the Wehrmacht, including the medical services.

“Sanitätsdienst der Wehrmacht” – Various documents and archives available in German military archives or via specialized military history sites such as Lexikon der Wehrmacht (www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de).

“Kranken- und Verwundetentransport im Zweiten Weltkrieg” by Karl-Heinz Parschalk – An in-depth study of wounded transport in the German army.

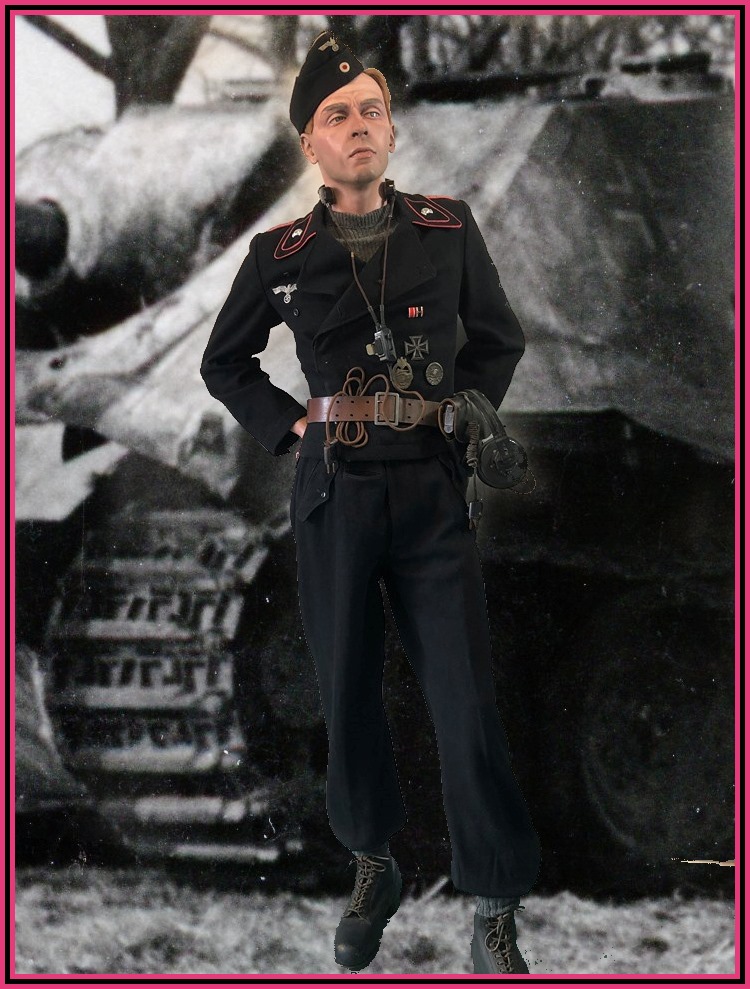

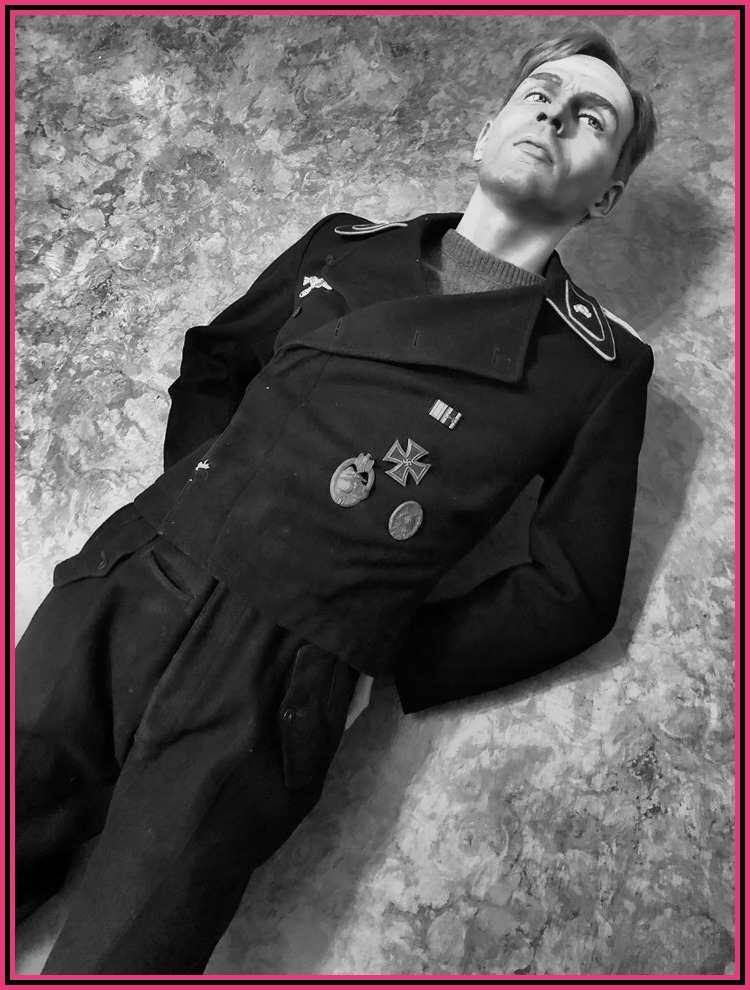

Schwere Panzerjäger-Abteilung 654

German veteran of the Russian front (combat since 1941), with the rank of Lieutenant:

tank commander belonging to Schwere Panzerjäger-Abteilung 654, an armored unit equipped with 45-ton “Jagdpanther” Sd.Kfz.173 tank fighters – Alsace, November 1944.

He wears an all-black cloth outfit, practical for these men who have to get in, move around inside and get out of the panzer’s highly compartmentalized space, sometimes very quickly when the situation calls for it.

An armored vehicle of this type is inevitably oily, dirty and more or less dusty, which easily explains the choice of black for this outfit.

The double-breasted jacket (Feldjack) features shoulder tabs edged in pink (the weapon color of the German Panzertruppen) and collar tabs, also in the weapon’s colors, with the famous skull and crossbones (the skull and crossbones are directly inspired by Frederick the Great’s Husaren-Regiment Nr.5 “von Ruesch”, dating from the mid-18th century).

Decoration ribbons and other awards are pinned to the left side of the jacket:

Verwundetenabzeichen “silver” (wounded badge for having been wounded 3 or 4 times in combat or seriously injured).

Bandspange EK2 und KVK(Kriegsverdienstkreuz) mit schwerter.

Iron Cross 1st Class (EKI)

Panzerkampfabzeichen “argent” (armored combat badge).

The pants (Feldhose) are of the same texture as the jacket, with drawstrings at the bottom of the legs.

The cap worn by this officer is decorated all around the flap with a small silver braid.

A model Walther P38 pistol in a leather holster is worn on the belt with a buckle.

Radio headphones and throat microphone are part of the on-board equipment.

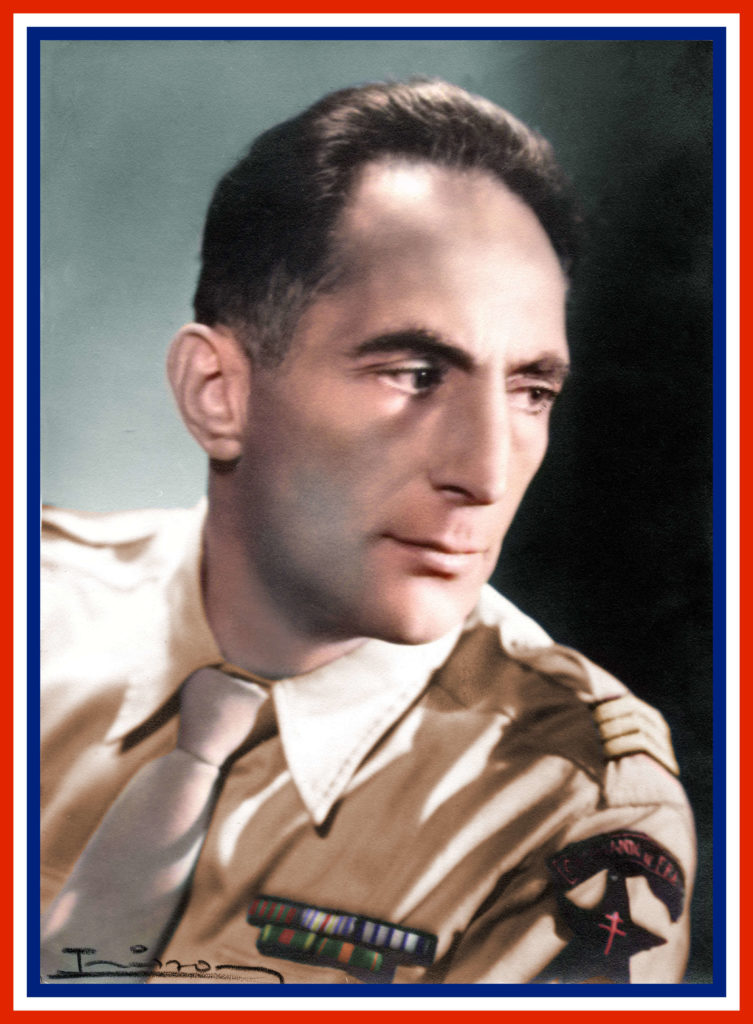

Frédéric Georges REINHARDT 1901 – 1964

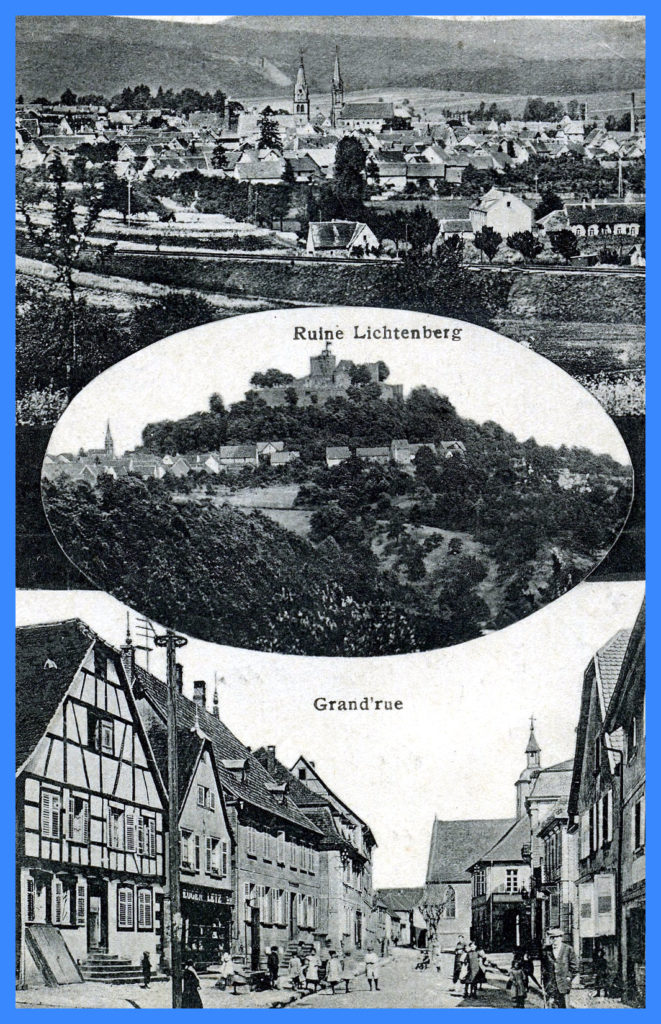

Frédéric Georges Reinhardt was born on October 24, 1901 in Ingwiller (67).

He has an older sister, Rika, born in 1899, and a younger brother, Robert, born in 1905. His father, Fritz Reinhardt, also from Ingwiller, is a building contractor, married to Marie Ehretsmann from Hunawihr (68). His mother died of tuberculosis in September 1907, and his father six months later, in February 1908, of grief, according to family recollections.

Within a year, the couple’s three children were orphaned and raised by their grandmother and paternal great-aunt, who ran a haberdashery in Ingwiller. Frédéric spent his entire childhood in Ingwiller.

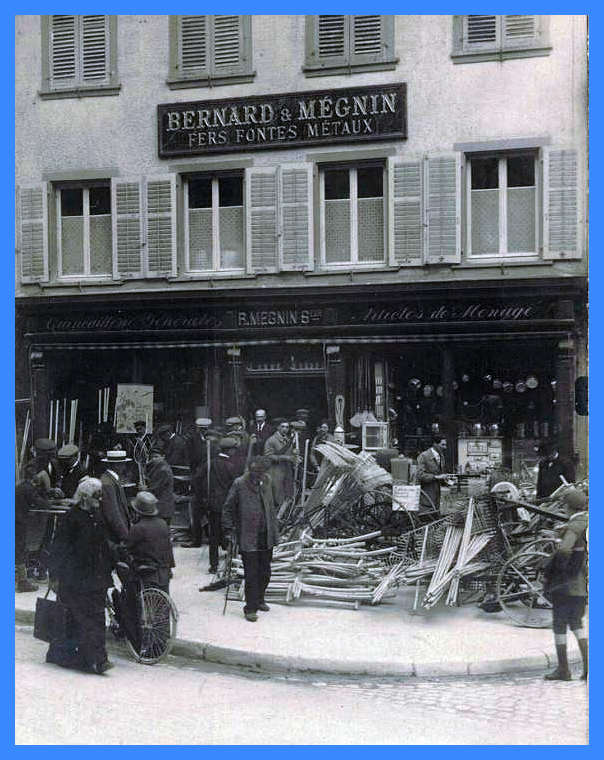

Around 1920, he completed an apprenticeship as a hardware merchant at a store in Strasbourg near Place Gutenberg. He then moved to the Paris region to work in Rueil, before moving to the Montbéliard region to take up a new job at BERNARD & MEGNIN, a hardware store.

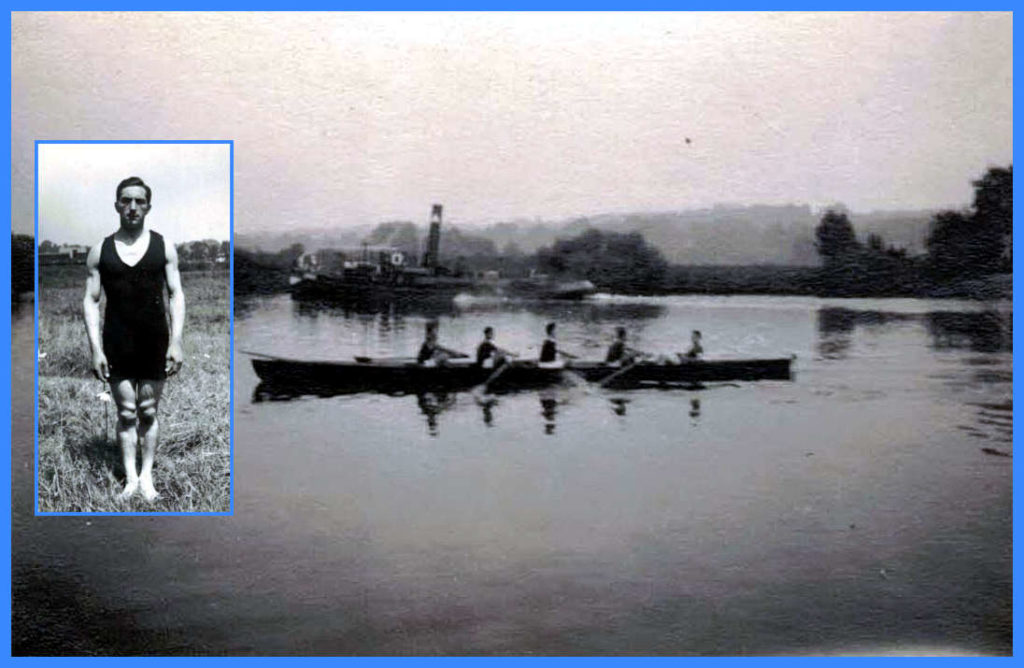

At the age of 18, he finished 1st in the Tour d’Ingwiller (67), and won a cup that his family treasures. He went on to take part in many other competitions.

A keen sportsman, he practiced gymnastics and rowing when he was in Rueil.

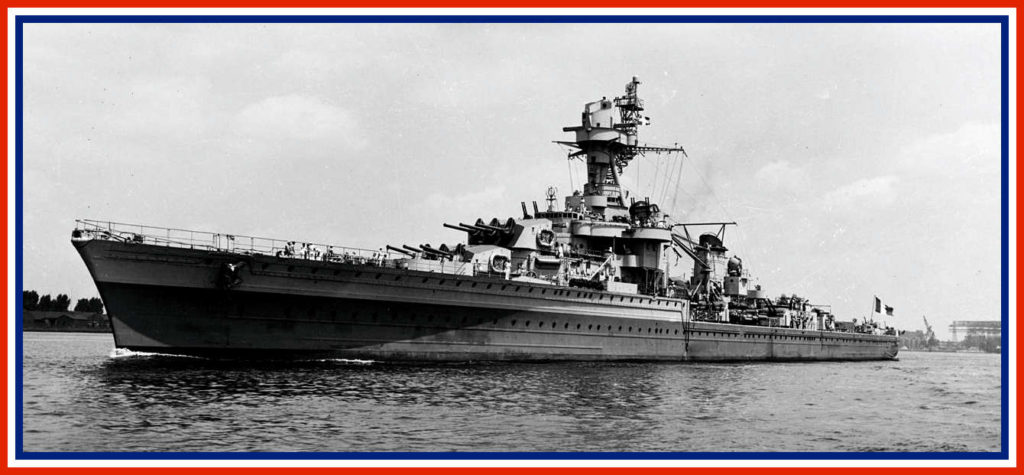

Class of 1921, he was drafted on April 5, 1921, and joined the fleet crew depot in Lorient on May 20, 1921.

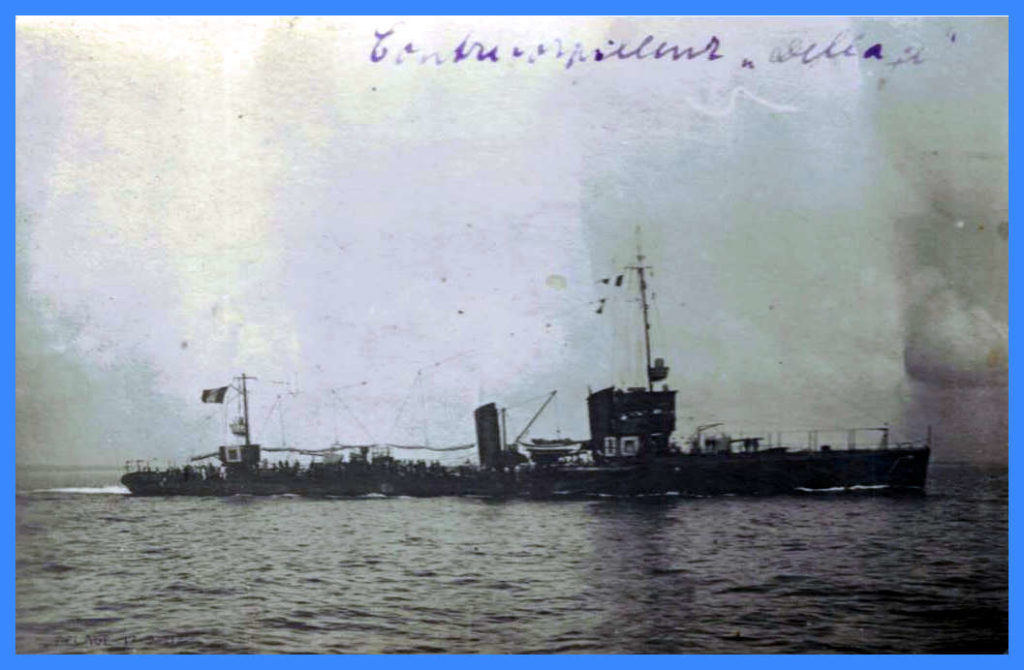

The H149 was launched in 1917 at the Howaldtswerke shipyard in Kiel. She was launched on March 13, 1918, and was not completed until 1920, when she was integrated into the Cherbourg shipyard on July 20, 1920, taking the name Delage (she was scrapped in 1933 and demolished in Toulon in 1935) – Reinhardt-Meyer collection.

He completed his military service on April 1, 1923 and was sent home on April 25, 1923 (he was granted a certificate of good conduct for the duration of his service).

On June 20, 1923 he was posted as a reservist.

On February 1, 1927 he was attached to the Centre Mobilisateur (CM) n°201 de Chasseurs. On December 6, 1934 he was attached to the Sélestat subdivision following a change of address (now living in Barr). On November 1, 1937 he was appointed corporal, then on October 15, 1938 master corporal.

He had a little cousin, Roland Bloch, who was his godfather (22 years older than him, due to a generation gap). As this godson lived in Barr (67), he visited him regularly, and it was certainly during his stays in Barr that he met his future wife, Berthe Willm, who was born on October 26, 1901 and also lived in Barr. They married in 1927 and had the joy of giving birth to their only daughter Marie-Madeleine Christiane on December 24, 1930, whom everyone called Marlène.

From 1927 to 1940, Frédéric and his family lived in Barr (67), where he worked for the Willm company, known at the time for its snail production and wines of the same name.

At the time, it was still relatively rare for an orphan like Frédéric, with no particular assets, to marry into a “well-to-do” family. This was certainly due to the fact that Frédéric got on very well with his father-in-law, who was the founder of the Willm company. The two of them share an entrepreneurial spirit. Throughout his life, before and after the war, Frédéric always had an entrepreneurial and innovative spirit. He filed a patent in the thirties for the creation of an object entitled “l’étend miel” (which remained confidential) and other patents.

He served 2 mobilization periods at Mutzig(67); the first in 1938 and the second in 1939: He was recalled on April 11, 1939 to the CM Infanterie n°202 and sent home on April 19, 1939. Appointed reserve sergeant on March 20, 1939. Following the events of summer 1939 and the growing risk of war, he was recalled on August 23, 1939 and transferred to the 223rd Infantry Regiment on November 4, 1939.

During the “phoney war”, he fights with his unit’s Corps Francs…

In June 1940, he was in the Rambervillers sector of the Vosges, where, after the town was taken by the Germans, he withdrew on June 20 to Brû with the last elements of the 223rd Infantry Regiment.

On June 21, 1940, at 2 a.m., Lieutenant-Colonel Languillaume, commanding the 223rd RI, decided to organize the defense of the village “for the sake of honor”, despite the inevitability of defeat and the request of the mayor and villagers not to resist, to avoid unnecessary destruction. At 9 a.m., the first German elements appeared in front of the French defensive line, marking the start of intense fighting (more than 600 shells fell on the village between midday and 7 p.m.) which lasted until 7 p.m.. By the end of the day, the men of the 223rd Infantry Regiment had run out of ammunition and could no longer cope with the final German charge, which claimed a few more victims. At 7.15pm, the enemy assembles all the prisoners in columns of three…the long and painful ordeal of captivity begins! Frédéric Reinhardt’s service record states that he took part in the French campaign from November 4, 1939 to June 25, 1940.

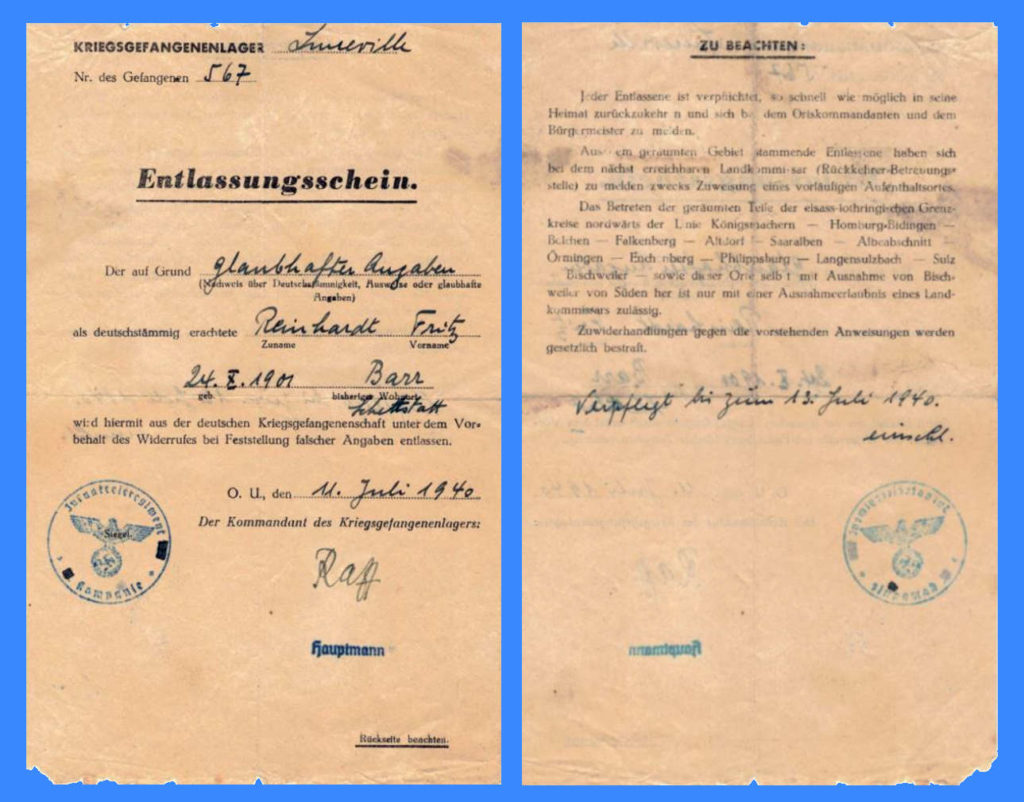

Following the Armistice of June 22, 1940, the majority of Alsatian and Moselle prisoners were released relatively quickly by the German authorities, who considered them to be German citizens and wanted them to return home as soon as possible…in order to Nazify the populations of the 3 départements (67-68-57) as quickly as possible. Frédéric, prisoner number 567, received his release order from the Lunéville Kriegsgefangenenlager on July 11, 1940.

Entlassungsschein,

Der auf Grund Glaubhafter ausgaben als deutschstämmig erachtete Reinhardt Fritz geboren 24.10.1901 in Barr wird hiermit aus der deutschen Kriegsgefangeenschaft unter dem Vorbehalt des Widerrufes bei Festellung falscher Angaben entlassen, den 11 juli 1940. Für kommandant des Kriegsgefangeenlagers : Hauptmann Raff.

Jeder Entlassene ist verpflichtet so schnell wie möglich in seine Heimat zurückkehren und sich bei dem Ortskommandanten und dem Bürgermeister zu melden. Ausdem geraumten Gebiet stammende Entlassene haben sich bei dem nächst erreichbaren Landkommi-sar (Rückkehrer-Betreuungsstelle) zu melden zwecks Zuweisung eines vorläufigen Aufenthaltsortes. Das Betreten der geräumten Teile des elsass-lothringischen Grenzkreise nordwärts der linie Königsmachern-Hömburg-Bidingen – Bolchen – Falkenberg – Altdorf – Saaralben – Albcabshnitt – Örmingen – Enchenberg – Philippsburg – Langensullzbach – Sulz – Bischweiller – sowie dieser Orte selbst mit Ausname von Bischweiler von Süden her ist nur mit einer Ausnahmeerlaubnis eines Landkommissars zulässig. Zuwiderhandlungen gegen die vorstehenden Anweisungen werden gesetzlich bestraft.

Verpflegt bis zum 13 Juli 1940.

Certificate of release,

Reinhardt Fritz, born on 24.10.1901 in Barr, considered to be of German origin on the basis of credible information, is hereby released from German captivity subject to revocation in the event of finding of false statements, on July 11, 1940. Iron commandant of the prisoner-of-war camp: Hauptmann Raff.

All those released must return home as soon as possible and report to the local commander and mayor. Persons released from the expelled area must report to the nearest Landkommi-sar (return assistance office) to be assigned a temporary place of residence. Access from the south to the evacuated parts of the Alsace-Lorraine border district located north of the line Königsmachern-Hömburg-Bidingen – Bolchen – Falkenberg – Altdorf – Saaralben – Albcabshnitt – Örmingen – Enchenberg – Philippsburg – Langensullzbach – Sulz – Bischweiller – as well as to these localities themselves, with the exception of Bischweiler, is only permitted by dispensation of a district commissioner. Violations of the above instructions are punishable by law.

Supplied until July 13, 1940.

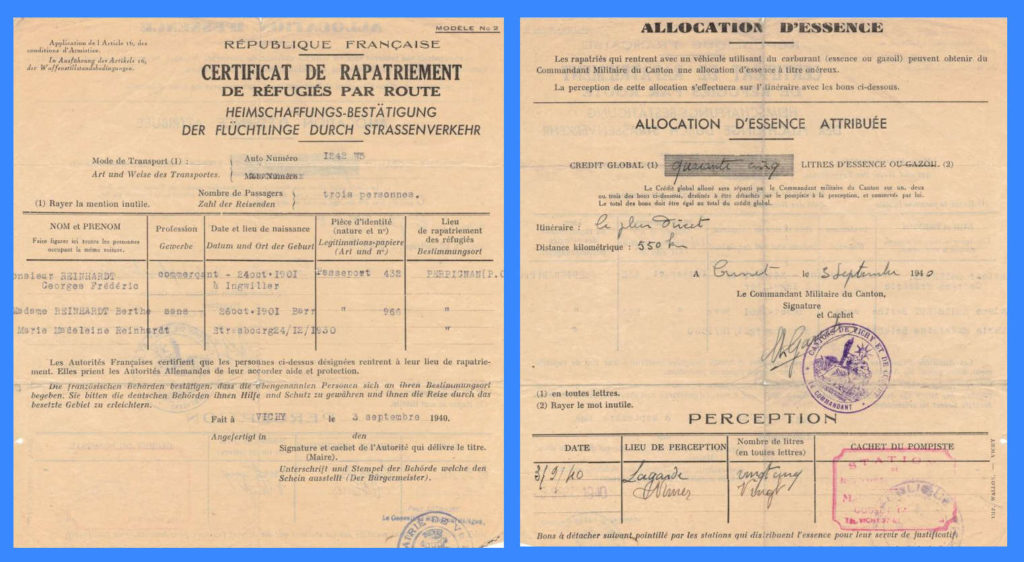

Very soon after his return home, he prepared the family’s departure from Barr for the free zone, as for Frédéric it was inconceivable that they would have to live under the Nazi yoke (he had certainly anticipated a possible expulsion due to his strong Francophilia). On September 1, 1940, the entire Reinhardt family left Barr by private car, on the pretext of a trip to Lyon to buy corks for Willm’s wine bottles. To make it look like a short stay, there was no heavy luggage, so Frédéric’s wife dressed Marlène with twice as many clothes on her.

After being turned away for the first time, Frédéric and his family found a second crossing point and managed to cross the demarcation line unharmed. The real destination of their journey was the town of Pertuis in the Vaucluse region, as Frédéric’s younger brother (Robert) was able to take them in through his in-laws who lived there.

He was demobilized on September 5, 1940 by the Nîmes demobilization center, where he stopped before joining his brother in Pertuis.

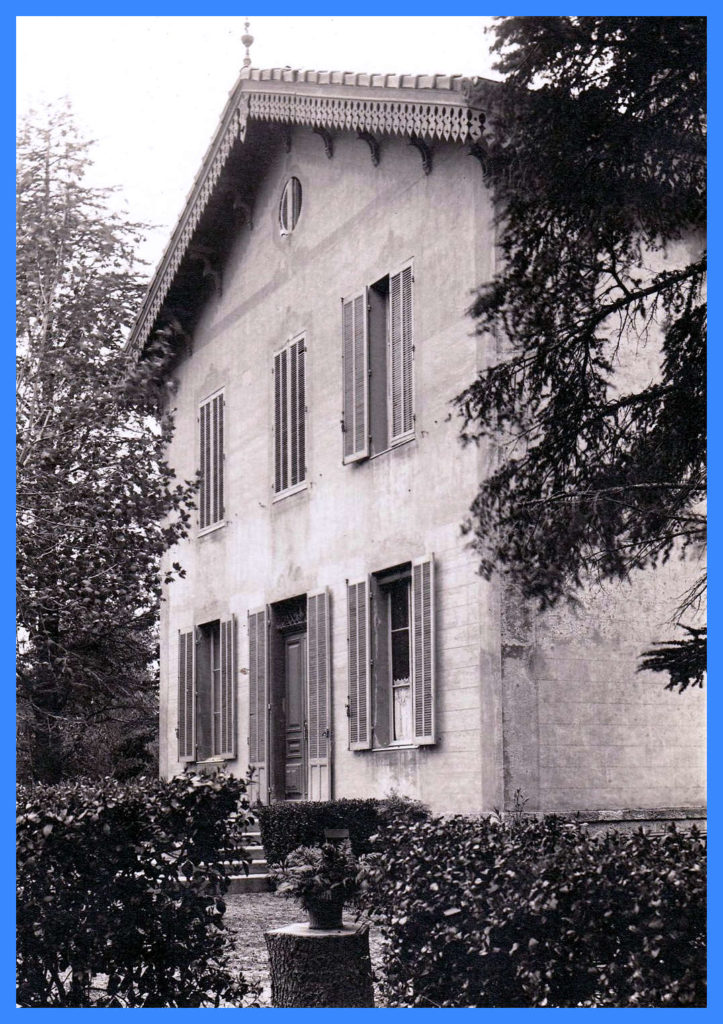

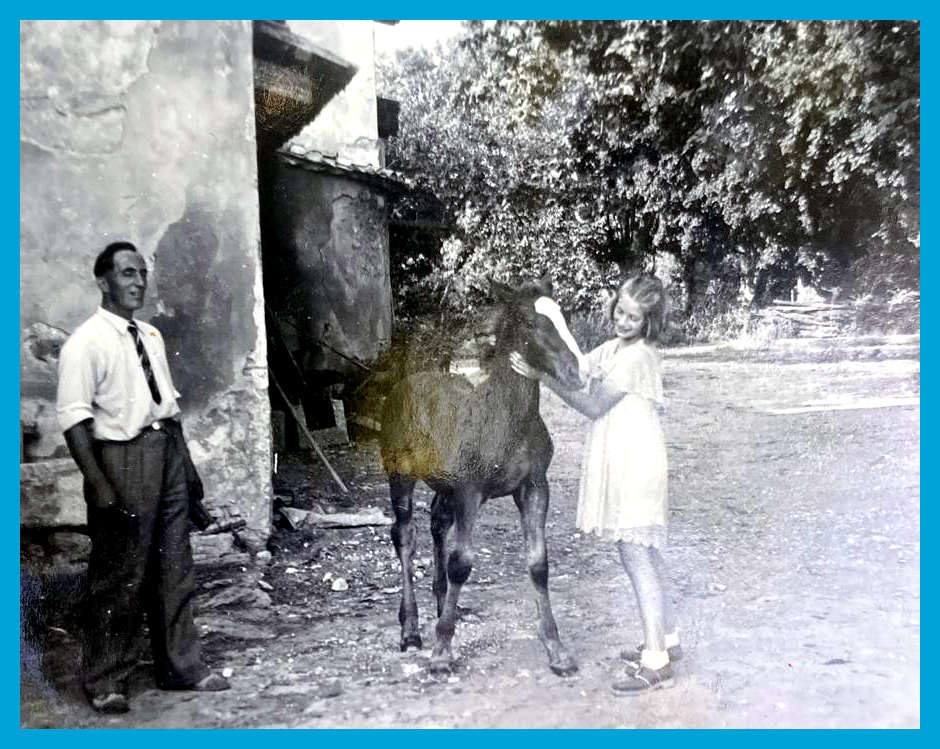

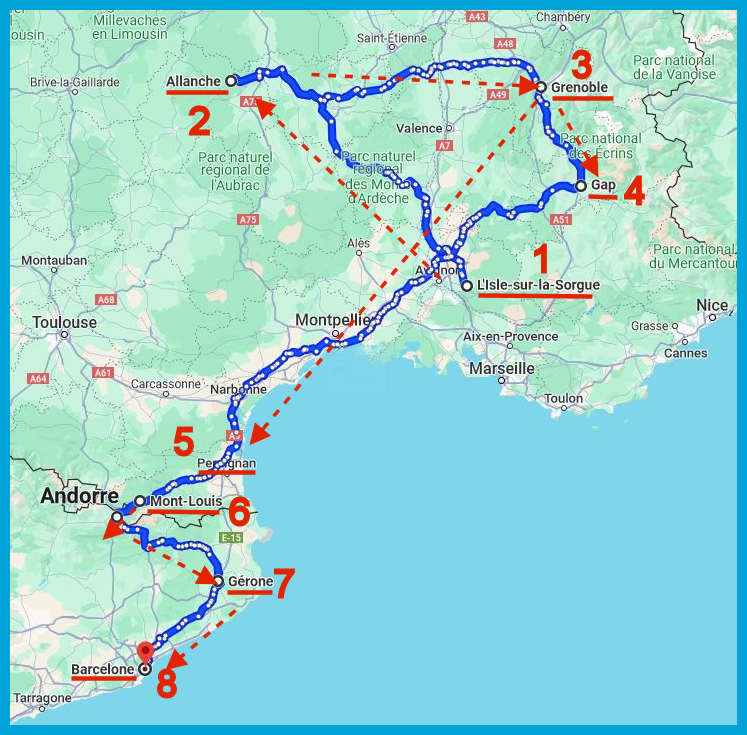

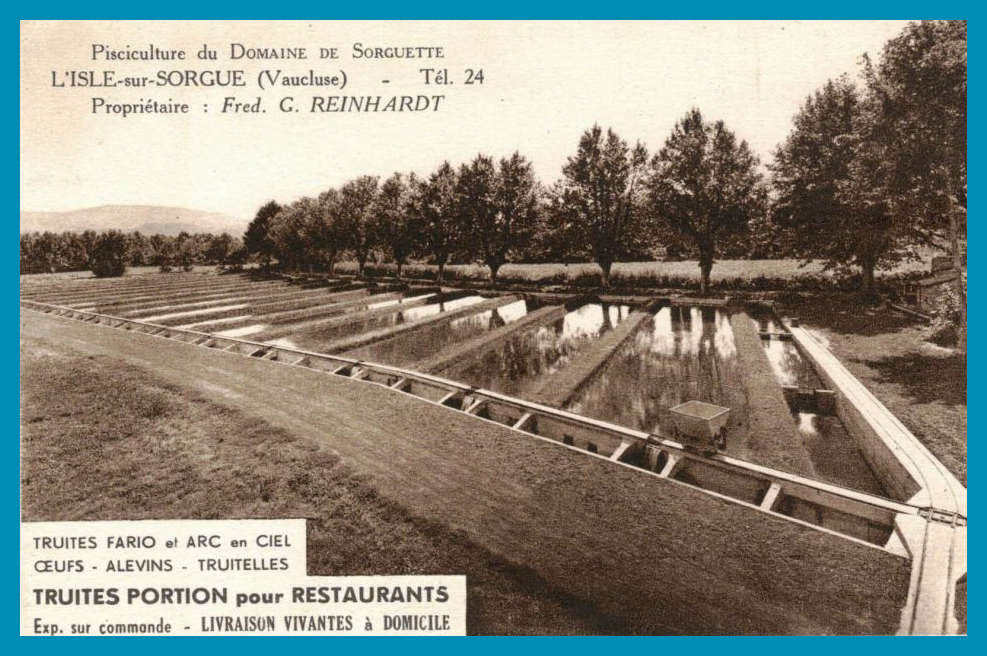

They spent a month looking for a farm to buy, and found one in l’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue in the Vaucluse in early October 1940.

As a reminder, the Vaucluse department was the destination of Alsatians expelled from the Bruche valley by the Nazis, and a number of them passed through and stayed at Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, in their large house.

This postcard pre-dates 1940, but the house must have been in much the same condition when they arrived.

It was on the terrace to the right of the photo that Canon Bornert and Frédéric chatted while eating cherries in brandy (Marlène recalled after the war).

Their daughter Marlène, much later, told her son Jean-François about Canon Bornert of Molsheim (later arrested and deported to Dachau) and Molsheim deputy mayor Henri Meck, both of whom had been expelled by the German authorities.

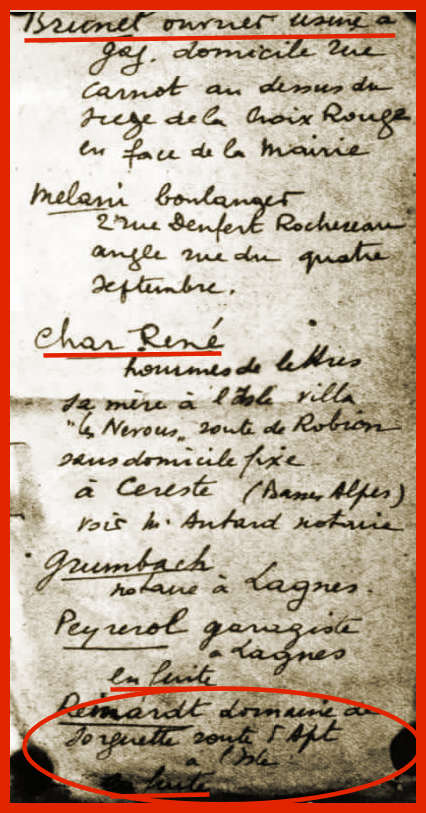

We don’t know if Frédéric Reinhardt was active in the Resistance in Vaucluse, but in July 1943, the Vichy militia suddenly arrived at his home to arrest him!… for the record, a few years ago, one of his grandsons met a former Resistance fighter in Fontaine de Vaucluse, who told him that when the Resistance fighters saw this fellow (Frédéric) with his German accent come ashore, they wondered if they weren’t going to “shoot” him!

Luckily, he wasn’t there that day, but he had to go into hiding and start a clandestine life. He spent some time in the surrounding hills, and came in the night to see his daughter and his wife. Frédéric left Isle-sur-la-Sorgue for Allanche, and after his departure his ailing wife went to the Charentes region, where Frédéric’s older sister was staying. Marlène, barely 13 at the time, remained alone in the big house for some time, with just Alphonse Hornecker and his family living in a house next to the farm. The Hornecker family had been expelled in 1940 (Alphonse had spoken ill of the Nazi regime in a bistro in 1940) and were originally from Urmatt. Alphonse worked on the farm in Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, and the farm was subsequently occupied by the German army.

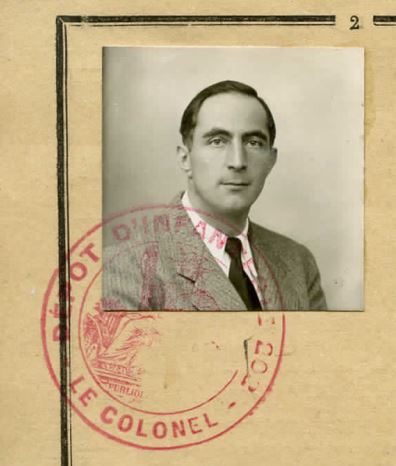

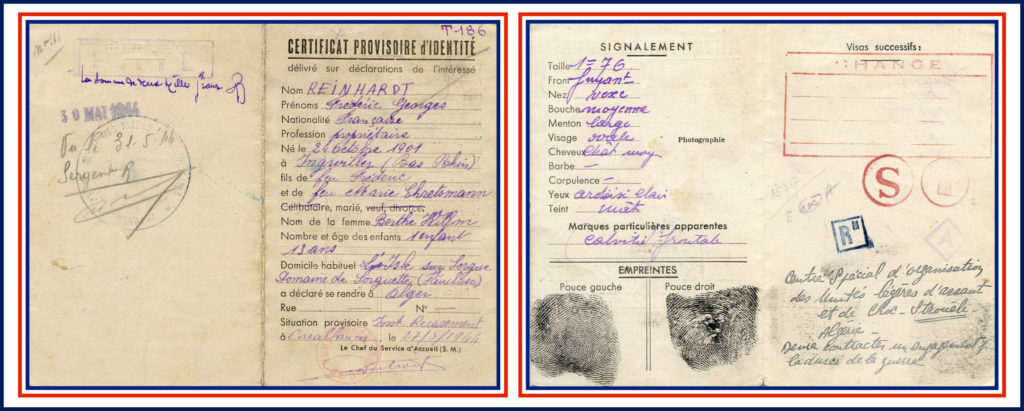

His daughter “Méjélé” joins him in Allanche in the Cantal (a young man sent by Frédéric to pick up his daughter and take her by train to her father. The journey ended on foot in 20 cm of snow), but following a denunciation they had to leave in a hurry and headed for Grenoble. In Grenoble, Frédéric had false papers made to leave France, while his wife (who had joined them) and daughter took refuge with a friend, Madame Ferber, who lived in Gap, where they remained in hiding until her liberation on August 20, 1944, before returning to their home in Isle-sur-la-Sorgue in September 1944.

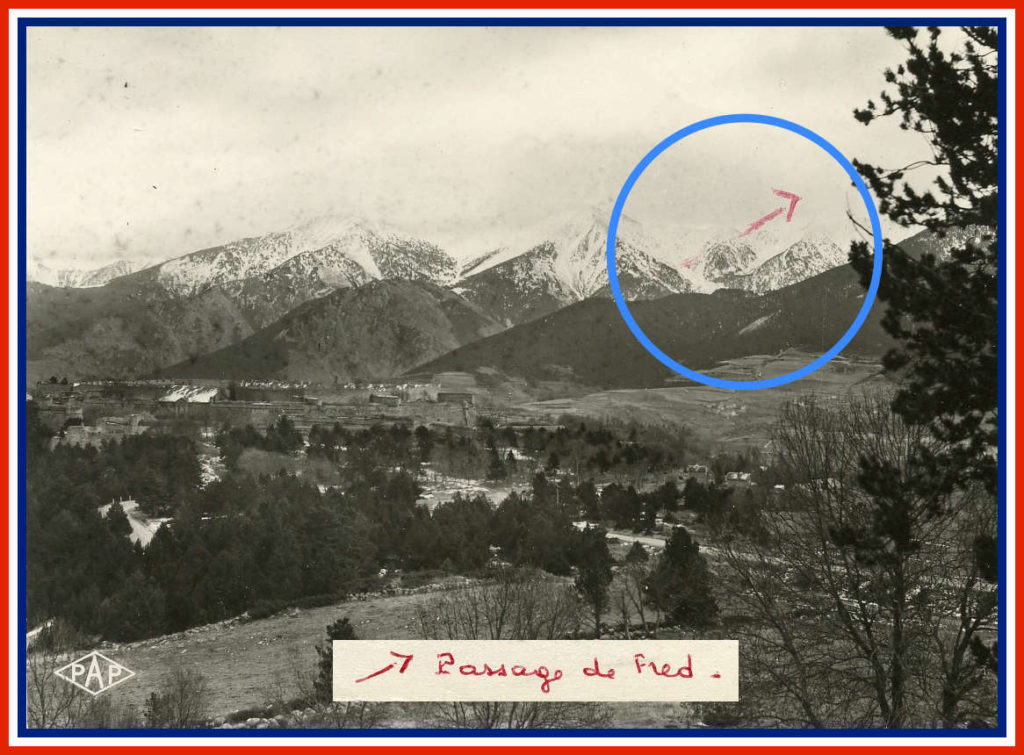

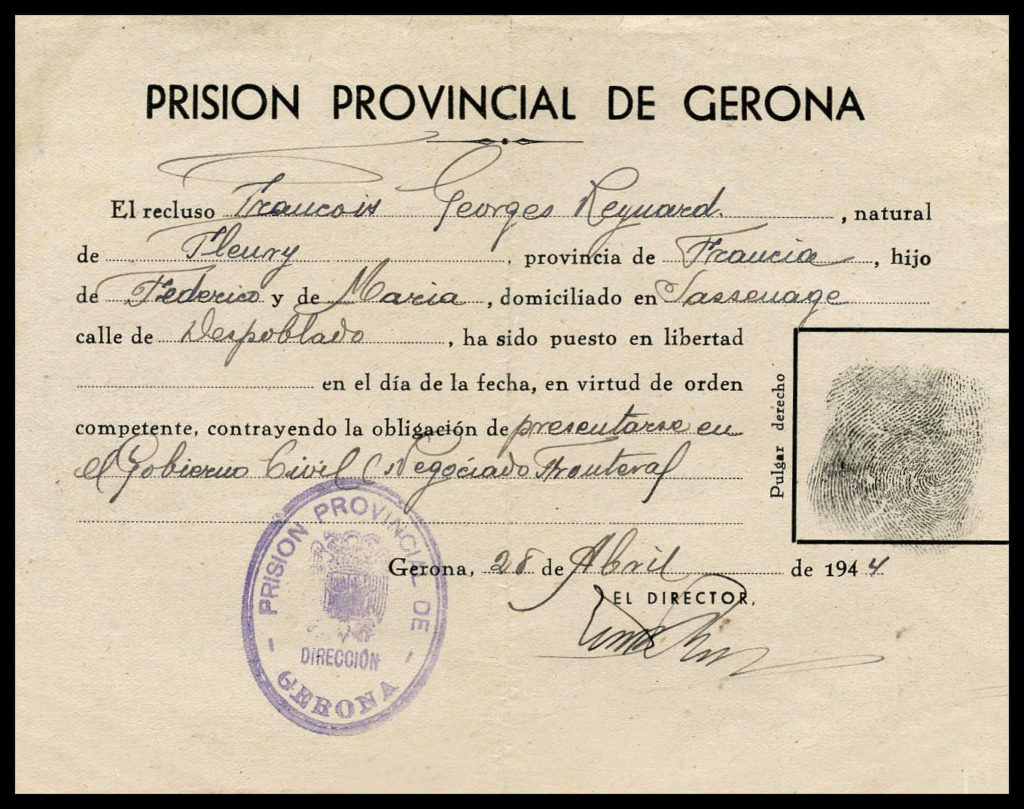

Having escaped from France on April 24, 1944, Frédéric crossed the Pyrenees near Mont Louis, where the brother of a dentist friend in Strasbourg, Monsieur Wennigger, owned a house that could serve as a base camp for his departure. He had difficulty crossing the Pyrenees on foot, due to the heavy snowfalls (and the cold), which in some places reached up to his waist. He managed to cross the passes and arrived in Girona, where he was imprisoned (like so many other brave Frenchmen in Spanish jails). Almost certainly because of his age, 40, he was released very quickly compared with the younger men, most of whom spent months there before being able to reach North Africa…

el recluso François Georges Reynard, natural de Fleury, provincia de francia, hijo de frederico y de Maria, domiciliado de Sassenage calle de repoblavo, ha sido puesto en libertad en el dia de la fecha, en virtud de orden competente contrayendo la obligation de presentarne en el gobierno civil negoéravo fronteraf. gerona, 28 de Abril de 1944 . El director. Prison provinciale de Gérone

The prisoner François Georges Reynard, originally from Fleury, province of France, son of Frédéric and Maria, domiciled in Sassenage, rue de République, was released today, by virtue of a competent order, under the obligation to report to the border civil government. Gerona, April 28, 1944. The director – Reinhardt-Meyer collection.

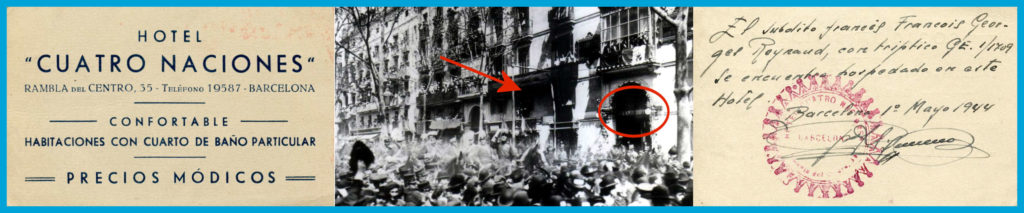

In Spain, he left Girona for Barcelona, where he stayed at the Grand Hôtel des 4 Nations, before crossing the Mediterranean to North Africa…

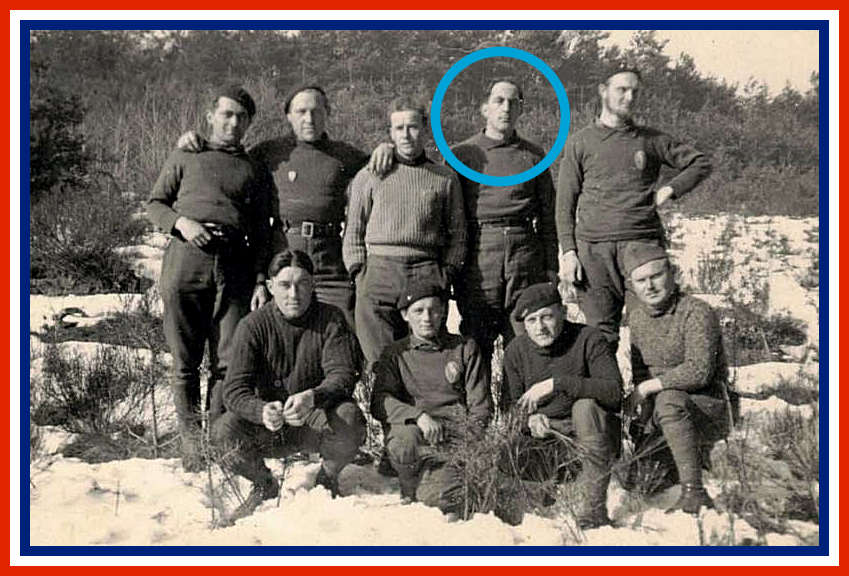

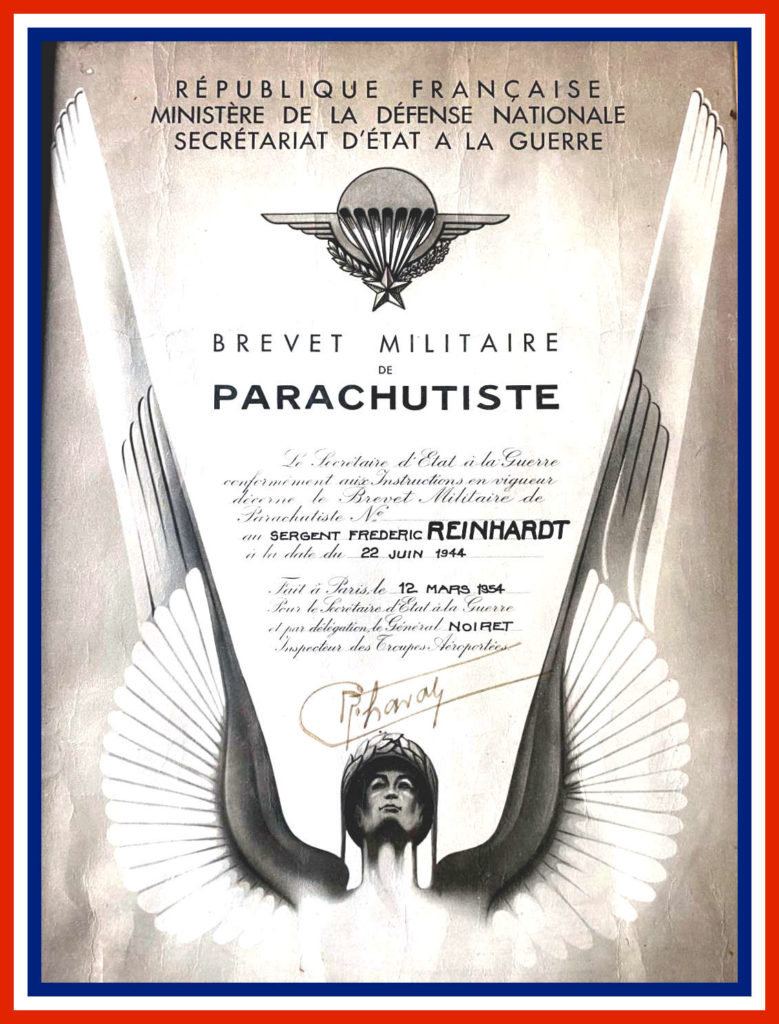

…where he joined the French commandos on June 5, 1944.

The 2nd Commando de France was formed on June 6, 1944 exclusively from volunteers who had escaped from France.

Parachuted and trained in the Staouéli and Sidi-ferruch region under the command of Captains Tersarkissof and Villaumé.

He was promoted to staff sergeant on July 1, 1944.

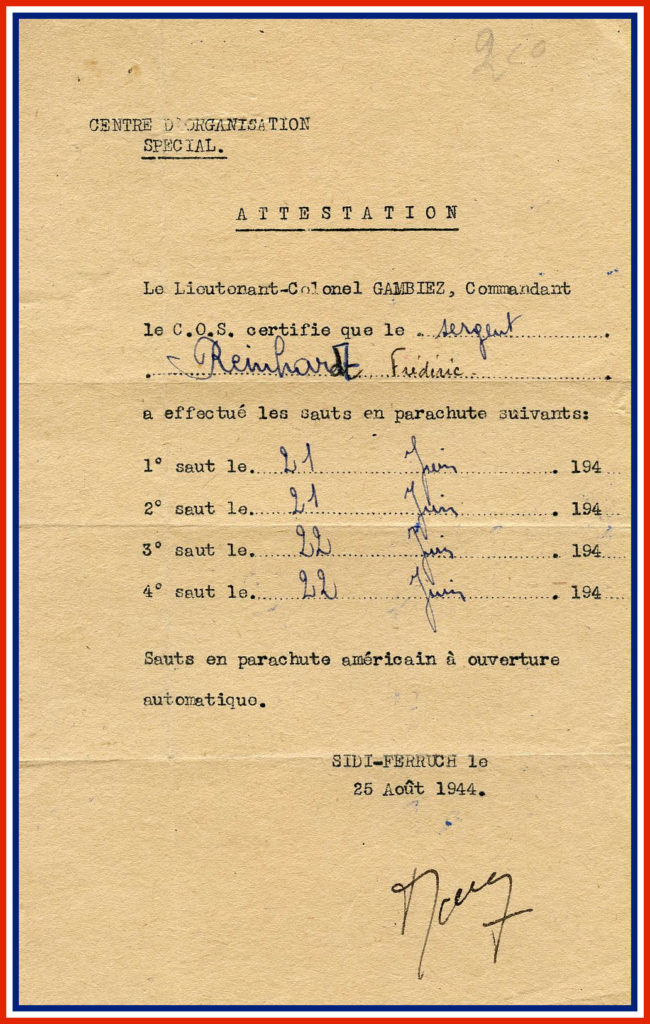

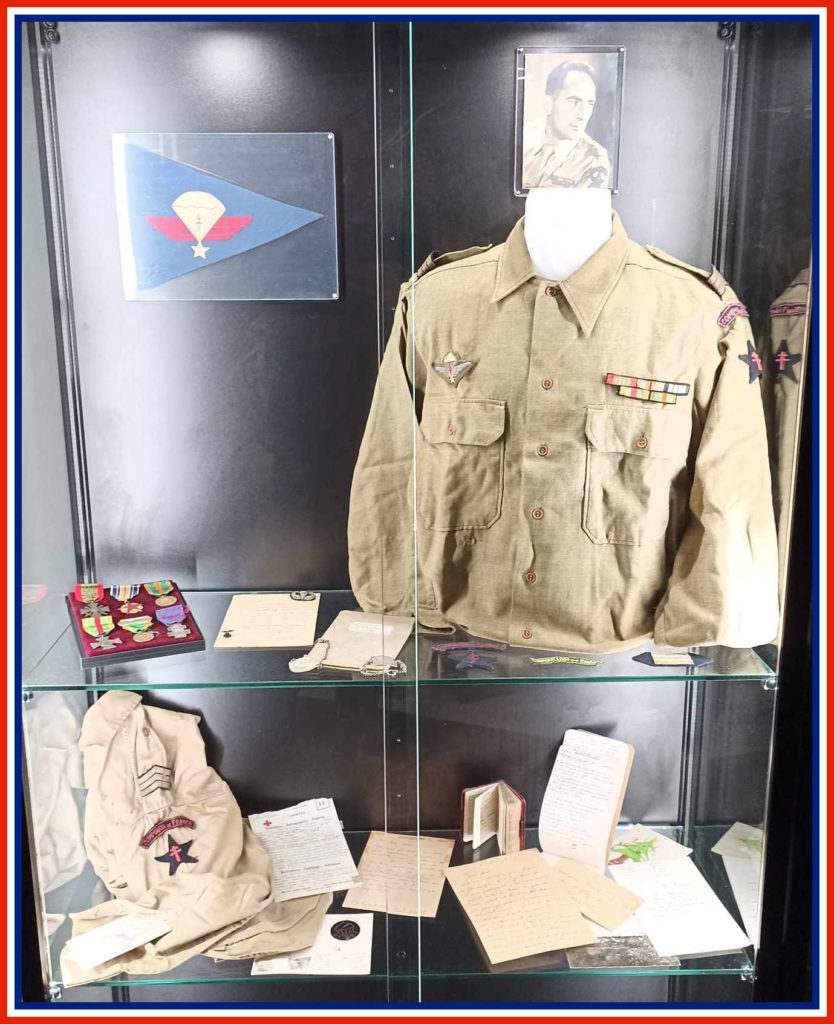

Frédéric Reinhard officially obtained his US Para brevet on August 25, 1944, and his certificate was signed by Lieutenant-Colonel Gambiez, commander of the Bataillon de Choc and Commandos de France.

To this end, on June 21 and 22, 1944, he made the 4 jumps required by automatic opening regulations.

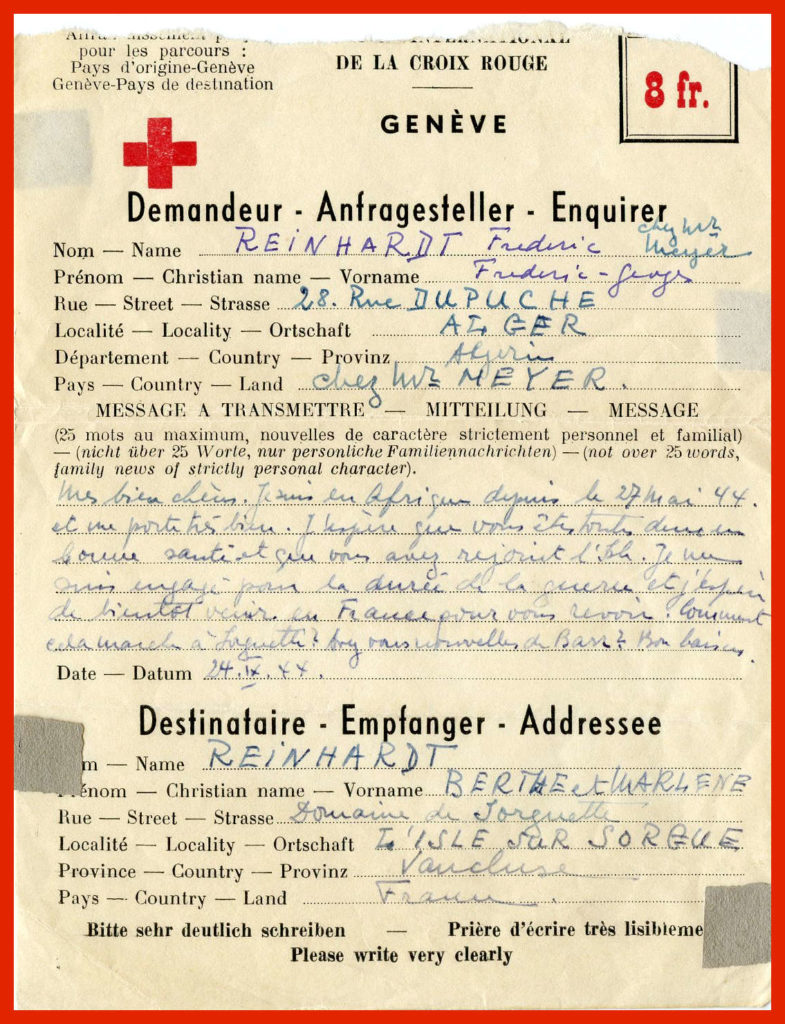

On September 24, 1944, Frédéric Reinhardt sent a message (which cost him 8 francs) through the Red Cross to his wife and daughter to give them news of him.:

“My dears. I have been in Africa since May 27, 1944 and am doing very well. I hope you are both in good health and that you have returned to Isle. I have enlisted for the duration of the war and hope to come to France soon to see you again. How are things at Sorguette? Have you heard from Barr? Bon baisers”

On October 2, 1944, “Fred” wrote a letter from Algiers to his wife and daughter, expressing concern that he had not heard from them, nor had he received a reply to his first 2 letters. In it we learn that he did cross the Spanish border, but with great difficulty. He arrived in Casablanca on May 27, 1944, where he immediately enlisted in the Bataillons de Choc, which a few days later became the Commandos de France. According to him, he was assigned to the 1st group of the Commandos de France, 2nd Commando, 4th platoon. He talks about all the courses he took: runner, parachutist, scout, killer, close combat, German weapons, German anti-tank gun, explosives…and all the training for elite troops. He can’t wait to begin the fight against the Nazi occupiers…

“We’ve been ready for action for 2 months and we’re still here. We are constantly on alert and never leave…I can’t wait to get to France to meet you at Sorguette and I hope to see you there…”.

One senses the man’s determination to liberate his homeland, whatever the cost: “Despite very hard training with men aged between 19 and 25 (he’s 43), I’ve held out for all the reports, but I feel I’m growing old normally. I don’t regret being in this elite corps and I’ve done everything to be ready for the rematch, and if we couldn’t do anything, it’s not our fault. We were promised that we would be the first to be parachuted into France…we were ready for anything and we were forgotten”.

He also asks for news of his dear Berthe and his little “Méjélé”, asking several questions: “…how did you live in Gap?…did the Germans bother you after I left? did you suffer from the fighting to liberate the region? when did you return to Sorguette? is there any damage? how are our family and friends…? He ends his letter with “a big kiss to you both and see you soon, your dad”.

NB: his grandson Jean-François, having spoken with some of his companions, remembers him as a character who marked them, Monsieur Jourquin repeating to him several times “your grandfather was somebody”! He also told him that during the umpteenth delayed departure to liberate France, Frédéric had angrily stabbed his commando dagger into the ship’s rail, loudly expressing his displeasure.

The 2nd Commando de France landed with the cruiser “Montcalm” at Toulon on October 10, 1944.

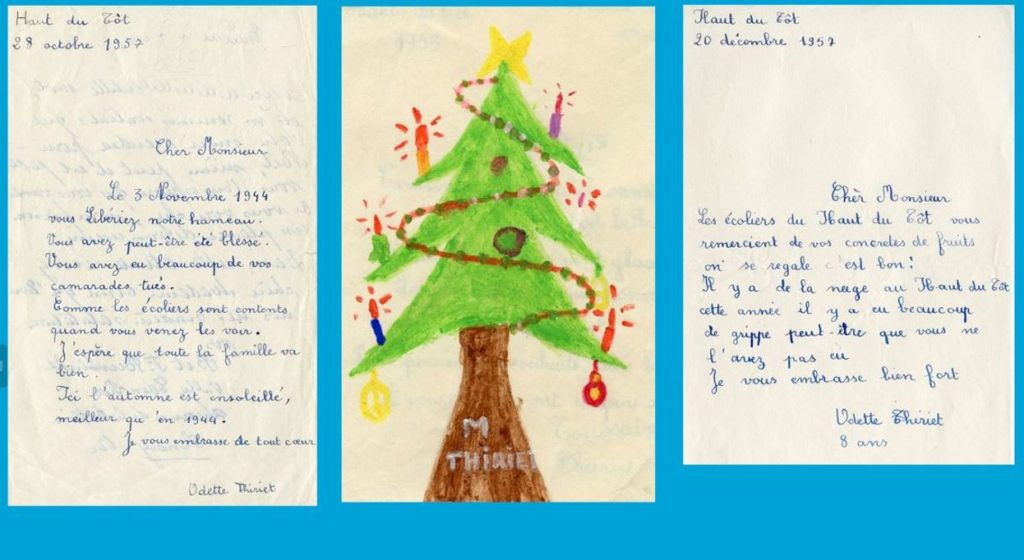

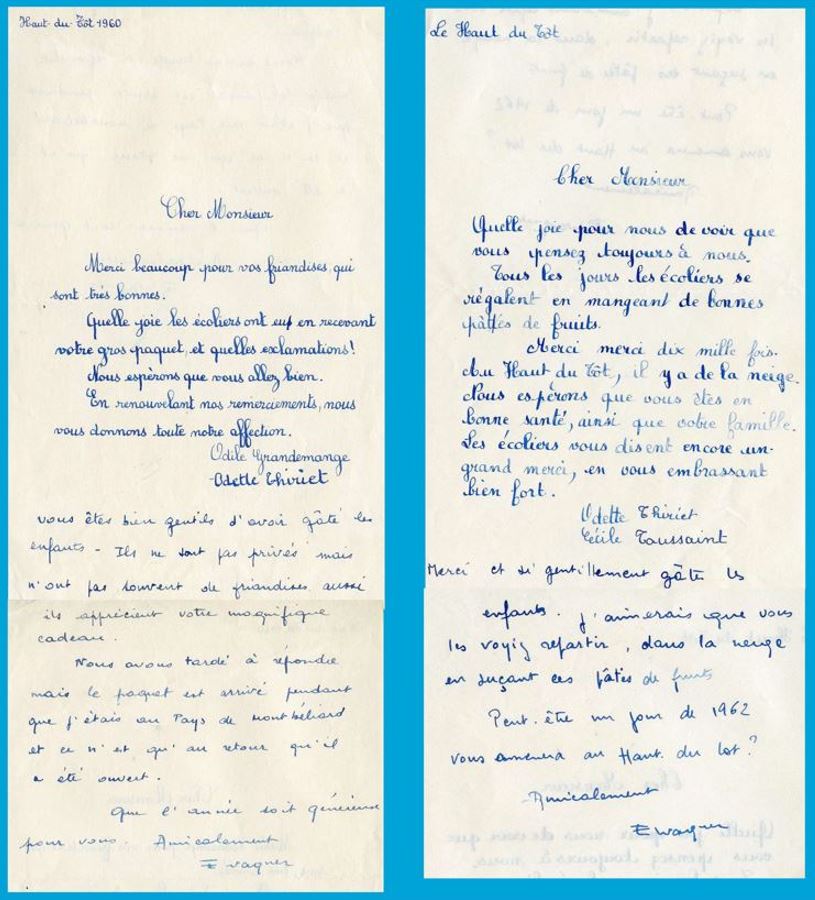

The Commando de France fought its first battle on November 3 and 4, 1944 at Haut-du-tôt and suffered its first casualties (24 men killed, most of them from the 1st Commando, and around a hundred wounded).

On November 9, 1944 “Fred writes in a letter to his daughter ”…it’s already pretty cold here and today there’s snow…we’re off the line after 5 days of very hard fighting. The worst part was the artillery and mortar bombardment in preparation for the enemy’s counter-attack…despite everything, we had to stay put and take it…We had 25% casualties in killed and wounded…our battalion behaved very well despite the fact that many of them were in the fire for the first time. …the rain didn’t stop for days, sleeping and living outside without a roof isn’t very enviable…lots of kisses to your darling mom, always be good my dear little one and help her while you can”.

On November 19 and 20, 1944, they took Essert against 2 German companies: in eight hours of fierce fighting, 18 commandos were killed. The fighting continued unabated with the liberation of Belfort, where they were among the first to enter on November 20, 1944.

On Saturday November 25, 1944 “Fred writes in a letter to his dear little Méjélé ”…We were engaged and had fierce fighting with the Boche. We took Belfort after infiltrating the village of Essert, 3 km away. All night and morning we had to endure German counter-attacks, and street fighting lasted until 3pm. At that point, our tanks were able to arrive and we rammed into Belfort, which we liberated at around 6am. The people were overjoyed! From there we liberated other villages and hamlets. Last night was the first time we’d slept under a roof, but morale was still superb. Yesterday I was on patrol and we were in Alsace”.

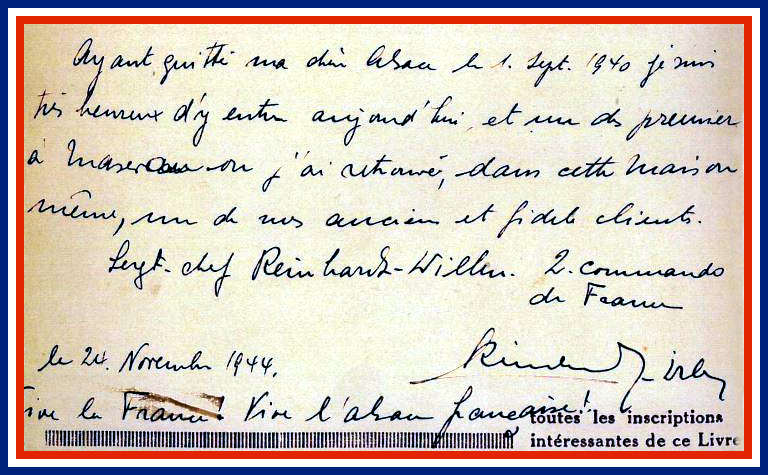

During the Alsace campaign, the French commandos fought in Masevaux between November 25 and 28 (16 killed). On November 26, 1944, the day Masevaux was liberated, Frédéric Reinhardt was one of the first French soldiers to enter the town, according to Mr. Gebel, owner of the “L’Aigle d’Or” hotel-restaurant in the town center: “On November 26, 1944, Mr. Reinhardt visited me at the cellar. He was the first French soldier we’d seen in over 4 years. We toasted with one of my bottles of Gewürztraminer that I had hidden from the Germans”.

November 30, 1944 “Fred writes a letter in Masevaux libérée: ”…For the last two days we have been in reserve…we have spent 15 days which were not very restful…we had a fierce battle at Essert which is the key to Belfort…. despite our losses, we took and held the village against an enemy that was far superior in numbers…we killed many of them…the fight lasted from 3 a.m. to 3 p.m., when our tanks arrived, having been stopped by the anti-tank ditches, and with which we returned to Belfort… 3h to cover 2.5kms…our section was the first to enter Belfort…from there we returned to the enemy rear towards Rougemont…finally the big day arrived with the entry of our troops into Alsace…we were still the first in Masevaux…what a joy for the population. We’re now in reserve, and it’s about time, because out of 31, we’re still 10… Backing down is a word that doesn’t exist for us, and we proved it at very critical moments… We were congratulated by our General de Lattre and by the great Charles”.

On the very day he wrote this letter, Frédéric and his comrades went to the Hundsruck pass in the Thann sector (68), at an altitude of 748 meters, to dislodge the German troops.

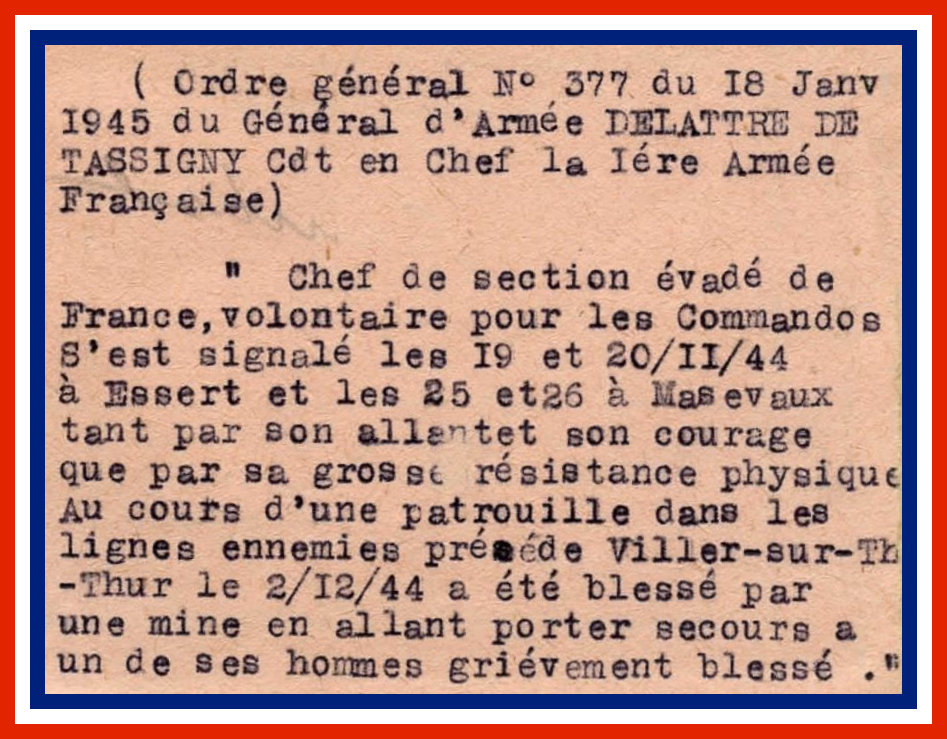

On Saturday December 2, Frédéric Reinhardt stepped on two mines while trying to rescue one of his men seriously wounded by a mine. He was wounded in the legs and head during a patrol with Aspirant Pérard (1 platoon) in front of Willer-sur-Thur and Bitschwiller-les-Thann (68) at around 7pm.

“On December 5, 1944, Fred wrote about what had happened to him: “I’m in hospital in Besançon. During a patrol on December 2, I received some mine shrapnel in my leg. I was lucky, others escaped with one or two missing feet.”

Back at the Thannerhubel, he was quickly treated by Bordaguibel and Deficis, then transported to the Masevaux girls’ school, which had been transformed into an advanced first-aid post. He was evacuated from the Masevaux hospital at around 9am on December 3, followed by Rougemont and Lure, arriving in Besançon at 6pm for surgery at 9pm. On December 4, a splinter was extracted from his left eye, and on December 5, X-rays were taken of his feet, thighs and knees: 9 splinters in the right thigh and 1 in the left; left knees, 6 splinters; right foot, small splinters plus a sprain; multiple splinters in the right face, chin and hand. On December 7, his right foot was cast at the Ruty barracks in Besançon. On the 10th, he left at 4pm by medical train and arrived at the supplementary hospital of the Dijon major seminary. He was then transferred to Lyon and Marseille, where he hoped to spend Christmas 1944 with his family, as he wrote in one of his letters. Thereafter, he spent most of his convalescence at home in Sorguette, and made regular visits to the Avignon hospital until May 12, 1945. Barely “back on his feet”, we learn from a press article in the Dernières Nouvelles d’Alsace (DNA) of 26/11/1969 that in May 1945, “a gentleman in civilian clothes, hobbling, helped by a cane, got out of a car on the Place Clémenceau…it was Mr. Reinhardt!” who apparently chose to return to Masevaux for one of his first trips.

For his action in combat he was awarded the following citation

“Section leader, escapee from France, volunteer for the commandos. He distinguished himself on November 19 and 20, 1944 at Essert(90) and on November 25 and 26, 1944 at Masevaux(68) both by his drive and courage and by his great physical stamina. During a patrol in enemy lines near Willer-sur-Thur(68) on December 2, 1944, was wounded by a mine while going to the aid of one of his men who was seriously wounded”. This citation includes the Croix de Guerre 1939-1945.

At the end of January 1945, the remainder of the Commando team continued to fight at Durrenentzen (44 killed) against the formidable Gebirgjäger of the 136th Regiment of the 2nd Gebirgs Division, an elite unit of German mountain troops, and several armoured vehicles.

After the reduction of the Colmar pocket on February 9, 1945, the survivors of the Commando de France were rested at Orschwihr (68) until March 31, 1945, before taking part in the German campaign. The 2nd French Commando was the first to cross the Rhine in early April 1945. It took part in all the battles: Karlsruhe(03-04-1945), Pforzheim(5 to 8-04-45), Langen Brand(14-04-1945), Black Forest, Pfollingen, Walvies. It ended its victorious journey in Austria at Bregenz, Rankweil and finally on May 8, 1945 at the summit of Vorarlberg, where they planted the flag bearing their colors.

The joy of Victory over the Nazis is overshadowed by the many comrades who are missing or wounded: 134 killed (including 102 during the Vosges and Alsace campaigns), 21 missing and 393 wounded.

Frédéric Reinhardt was demobilized on June 26, 1945, when he joined his wife and daughter, to be reunited once again at their farm “La Sorguette” in Isle-sur-Sorgue.

In July 1946, we meet up with his godson Roland (who, like 100,000 Alsatians and 30,000 Moselle residents, was forcibly drafted into the German army after August 25, 1942), who “disembarks” in Sorguette at the home of his uncle (with his consent) Frédéric Reinhardt, whom he affectionately called “Uncle Fred” after resigning from a stable civil service post in Strasbourg. Frédéric Reinhardt came to pick him up at Avignon station, welcoming him warmly, but as usual, he didn’t wait long to “curb” his godson’s enthusiasm, reminding him that he wasn’t coming for a vacation, but to work hard until he could find a solution for his professional future. Roland describes his dear Uncle Fred as follows :

“Anyone who didn’t know him can’t imagine the kind of man he was: physically handsome, with a strong character, a tireless worker, a family man, demanding of himself and others, but with his heart on his sleeve when it came to helping others or bailing out a friend, in short, a heart of gold hidden beneath a hard shell and, at heart, a great sentimentalist who avoided flaunting his reactions, very loyal in friendship and woe betide those who failed him. Not only did he always put his ideas into practice when he felt it was his duty to his family, his work and his country, he was always first to the task, setting a good example and sparing no effort to bring to fruition the projects he tirelessly concocted. For me, he will always remain a role model in every respect”.

Frédéric and his nephew broke down with their new car (the previous one having been stolen) on the N7 at the entrance to Orange, on their way to visit a supplier. As luck would have it, while waiting for a garage to help them out, Frédéric thought he recognized the Peugeot that had been stolen from him. Without saying a word, once he’d been helped out, Frédéric returned home to pick up the revolver he’d carried during his enlistment in the French army, and his friend Mr. Aymard, the garage owner, before returning to Orange to take a closer look at the vehicle, which bore a striking resemblance to his own. After a thorough examination by Mr. Aymard and his confirmation, Frédéric locked himself in the mechanic’s office to have a heated discussion with him (gun in hand), who had no choice but to admit his crime. Under guard (Roland and M Aymard), Frédéric went to the gendarmerie to lodge a complaint, but curiously, the maréchaussée tried to play down the affair. But “Uncle Fred” wasn’t one to be dissuaded so easily… the investigation would prove him right, as it was a gang of criminals specializing in car thefts, under cover of one of the gendarmes. That’s how he got his first car and…a fine and a few days’ suspended prison sentence for carrying a prohibited weapon of war, which was immediately amnestied because of his record of service during the Second World War.

After tidying up one of his cupboards in 1946… Frédéric set up a fish farm on his farm in 1947, which is still run today by one of his grandsons, Michael Meyer (the 3rd generation).

Until his death, Frédéric remained very close to the commune of Haut-du-Tôt, especially with the children of the village school, whom he visited regularly and to whom he sent a coli filled with sweets and fruit jellies every year, much to the children’s delight.

Sadly, he died suddenly on March 5, 1964 following a minor operation, at the age of 63, while still in good health and active in his profession. Having spent his entire childhood in Ingwiller, he is buried there in accordance with his last wishes. His beloved wife Berthe joined him in 1976.

His decorations:

His daughter Marlène has the joy of having eight children who still live in Provence, except for Jean-François who chose to go the other way round and return to Frédéric’s native land to live in Alsace.

Frédéric and Berthe have 8 grandchildren and 28 great-grandchildren, and the family continues to grow with new births.

The Musée Mémorial des combats de la poche de Colmar sincerely thanks Mr and Mrs MEYER Jean-Francois for donating his grandfather’s personal belongings, which today enable us to pay tribute to Frédéric Reinhardt and his Commandos de France comrades to whom we owe our Freedom!!!

LET’S NOT FORGET THEM!

…Sunday, October 27, 2024…

On Sunday October 27, 2024, we inaugurated the Frédéric Reinhardt showcase in the presence of descendants and family members, with the QR code dedicated to him by Jean-François Meyer, his grandson.

Our sincere thanks go to the brothers and sisters of the Meyer family for donating all of Frédéric Reinhardt’s artefacts and documents (“Marlène”, Frédéric Reinhardt’s daughter, is their mother and it was she who carefully preserved all of her father’s belongings throughout her life).

We’re delighted to have been able to inaugurate the showcase dedicated to him, which enables us to pay tribute to him and all his comrades in arms.

We ended the afternoon with a visit to the Musée Mémorial, recalling the tragic story of the liberation battles in the Poche de Colmar, and thinking fondly of all our liberators.

We would also like to thank Henri Simorre for his help and his keen eye for the subject.

To find out more about the history of shocks, we suggest you visit our forum : https://1erbataillondechoc.forumactif.com/

In addition…

NB concerning Alphonse Hornecker: he had a good friend who used to come to his farm in Isle sur Sorgue in the 50s… Albert Camus, who regularly came to Isle sur Sorgue to see the poet René Char, and who used to come and eat the omelette au lard at Alphonse’s house, as the latter welcomed him in a relaxed manner! At the time, Alphonse’s family no longer lived next door to Frédéric and Berthe’s, so Albert Camus was unfortunately never seen at Sorguette. Source: Jean-François Meyer.

sources :

Reinhardt-Meyer archives.

Bas-Rhin departmental archives

Lee William WHITESCARVER 1919 – 2002

Lee William WHITESCARVER was born on february 27, 1919, in Grand Island, Nebraska to Harry and Martha Whitescarver.

He attended schools in Pasadena, California and graduated high school in 1936.

A great-grandfather (Hermann Whistescarver) was born 12-26-1742 in Niederndorf, Germany.

Lee reported for duty in 1944 during world war II, as a rifleman in the US ARMY the 26 june 1944.

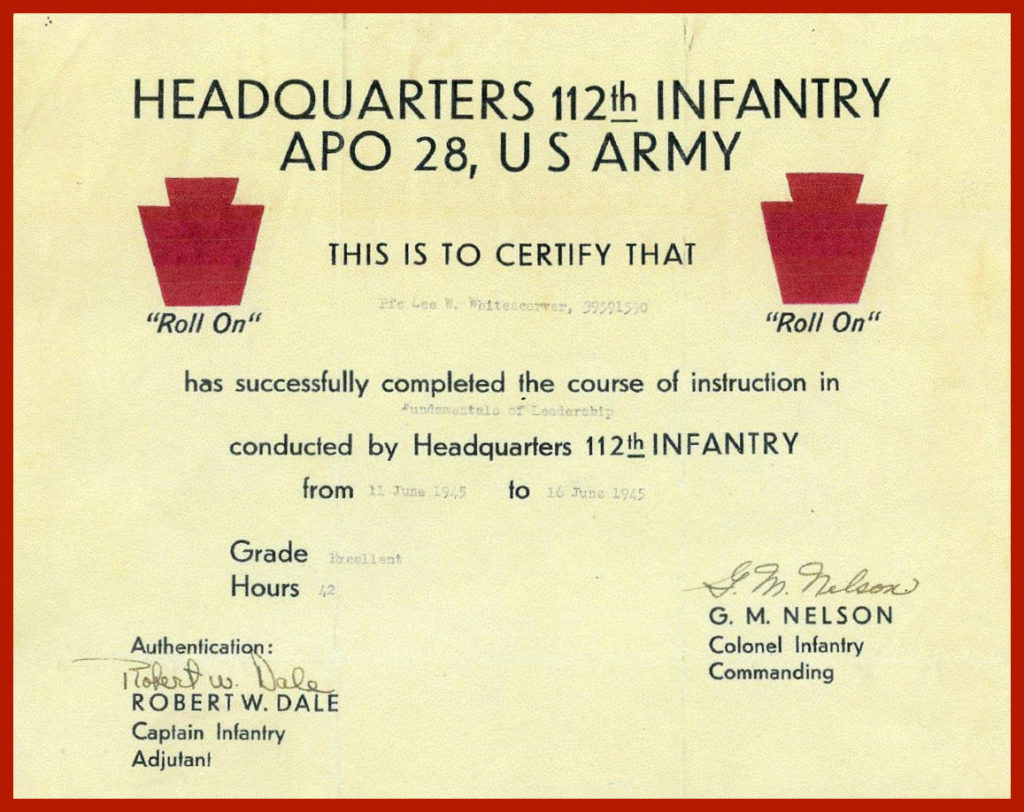

The Private 1st Class Lee W. Whitescarver, serial number 39591590.

He served with the 28th Infantry Division, 112th Infantry Regiment, III Batalion, Company K from August 1943 to december 1945.

The 28 ID US is the oldest American unit (created 1879). Its emblem is a red keystone symbolizing the state of Pennsylvania from which the division originates (Pennsylvania National Guard), hence its nickname “Keystone Division”, but also nicknamed by the Germans “Bloody Bucket Division” during the fighting in Hurtgen Forest.

Its motto is “Roll on”.

The 28th IDUS landed in Normandy on July 22, 1944, fighting in the ST Lô sector as part of Operation Cobra. On August 25, it crossed the Seine and entered Paris on the 29th. At the beginning of September, it crossed the Meuse, crossed the Belgian border, reached Luxembourg and on 9/11/1944 entered Germany, where it was given the task of securing the Hurtgen forest sector. It received the full force of the Ardennes counter-offensive. Because of the losses it suffered, it had to be withdrawn from the front. In January 1945, it was back in Alsace, where it played a major role in reducing the Colmar pocket from February 1 to 13, 1945. It continued to fight during the German campaign, ending its tour at Kaiserlautern.

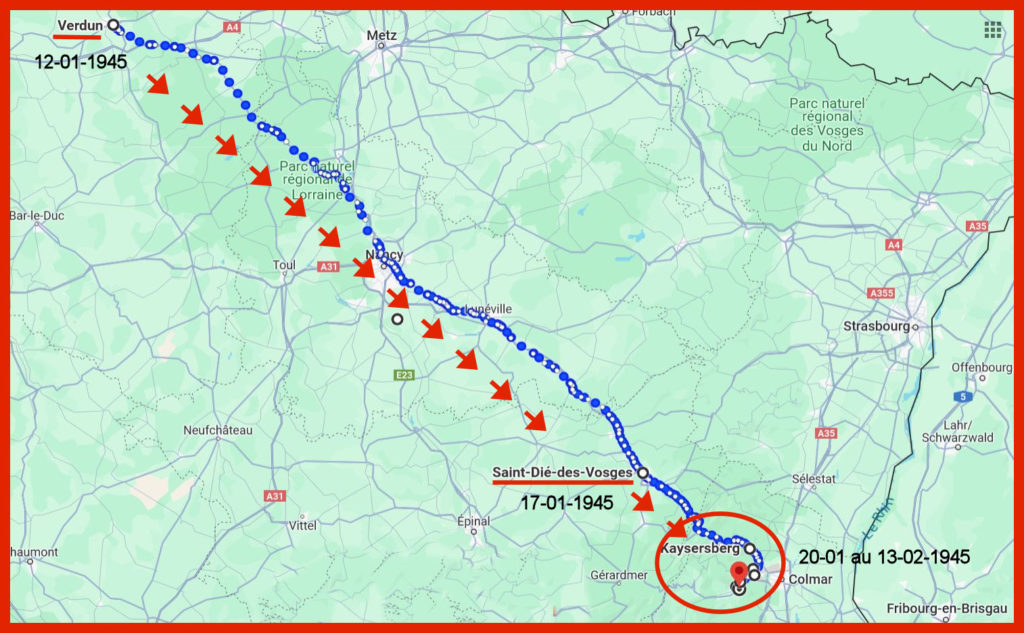

Company K of the 3rd Battalion of the 28th IDUS arrived in Verdun on January 12, 1945. On the 17th, it left Verdun and took the train to Saint-Dié in the Vosges.

From January 20 to 31, 1945, it was in the Kayssersberg – Bennwihr sector.

On February 2, Compagnie K headed for Niedermorschwihr (through minefields and slippery roads), which it liberated after a short engagement in which it took 25 prisoners but suffered 8 casualties.

On February 3, it began its attack on Turckheim, but came under fire as it approached. Captain THOMAS was killed by sniper fire. German counter-attacks and mortar fire cost them 3 more dead and 21 wounded, but the company held on to its positions.

On February 4, 1945, Company K liberated and cleansed Turckheim before being relieved by French troops in the evening.

It joined the rest of the Battalion at Ingersheim, from where it set off the following day to take the villages of Zimmerbach and Walbach.

It remained in the Forge sector until February 13, marking the end of the fighting in the Colmar pocket.

Rich, his son, tells us about his father :

“His regiment was active in Normandy, Northern France, Belgium, Battle of the Bulge (Ardennes) to the Rhine River. At one point the 28th became part of geenral George Patton’s third army. Dad never talk much about the war, but he had some entertaining stories of ‘Ole Blood & Guts” Patton (“our blood his guts”).

After VE Day, Sgt Whitescarver was stationed at the 28th Infantry HQ Camp Shelby, Mississippi. Dad was just one of a few who could type so he was assigned to the research staff to create their historical&pictorial hardback album of the 28th’s role in wwII.”

Lee ended the war with the rank of staff/sergeant.

Lee, a self-taught painter, began painting homes after the war in the Pasadena area. Painting homes became a true love of his, and he had a real talent at painting and was considered a true craftsman by his customers and competitors. By 1955 Lee had expanded his painting business into one o the most successful and largest painting and contracting operations in eastern Los Angeles County. In 1956 Lee, Ethel, Rich(Skip) and Cynthia moved into one of several new homes Lee had just built in Glendora, California.

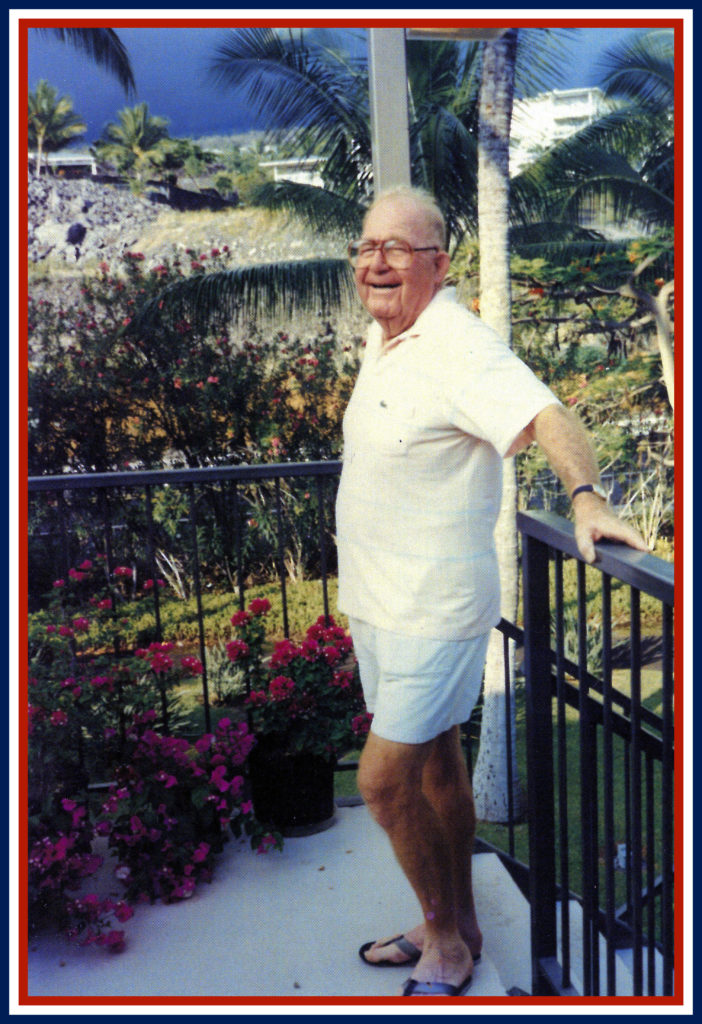

Then on March 28,1967 Lee and Ethel opened up village Color Center Inc. The store was a new concept, a specialty home decorating and paint store, and proved to be very successful. Soon afterwards it became the store competitors copied. Lee retired in 1981 and moved to Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, because as he said “I never thawed out after that cold winter of 1944 in Belgium during the war”.

Lee was a loving and caring husband, father “great papa” to his grand children. A true friend to the many people who passed throught his life.He will be truly missed by those who knew him. Lee his survived by his wife Ethel and his son Richard (Skip) of Twin Falls, daughter Cynthia of Glendora, California, 4 grand daughters and one great grand daughter.

Lee died May 24, 2002 in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii.

Dear Mr. Whitescarver, we sincerely thank you and your comrades of the 28th DIUS for your unfailing commitment and your participation in the liberation of our country.

We will not forget you!

We thank Rich Whitescarver and his wife for sharing his family history and donating his father’s garrison cap.

Raymond LUQUET 1923 – 2011

Raymond Louis Léon LUQUET was born on June 2, 1923 in RABAT, Morocco.

He joined Chantier de Jeunesse n°101 on January 29, 1943.

He joined the 1st Régiment de Tirailleurs Marocains (1 RTM) on

April 12, 1943, where he was assigned to the Compagnie Spéciale de

Headquarters on 11/5/43 at Staouéli in Algeria.

He transferred to the Bataillon de Choc on May 28, 1943 (reg. no. 141) and was assigned to the 2nd Company.

On September 13, 1943, he embarked at ALGER and landed at Ajaccio in Corsica the following day, where he fought with the 2nd Cie.

He was appointed Corporal on July 1, 1944.

Captain Lefort’s 2nd Cie landed on the island of Elba at 1am on June 17, 44, providing cover between San Piero in Campo and Fontana. It was during this fighting that hunter Raymond Luquet earned his first commendation, in the Division Order:

“F.M. marksman with great composure and a remarkable eye. Unable to cock his weapon as he advanced through crops, he fired his F.M. at enemies he spotted some 200 meters away. He shot down one of them, causing the others to scatter”.

This citation includes the Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with silver star.

Back in Corsica, he and his unit prepared for the Provence landings. The Bataillon de Choc was not part of the 1st wave, with the exception of the 30-strong CORLEY- MUELLE section parachuted over the Drôme on July 31 and August 1, and the 10 Chocs parachuted over LE MUY on August 15, along with over 5,000 Anglo-American paratroopers.

The Battalion landed in Provence on August 19 and fought its way into Toulon. Corporal Raymond LUQUET is cited in the Brigade Order:

“F.M. sniper, who protected the progress of his group in front of the Toulon Arsenal on August 22, 1944, under precise and terribly violent enemy fire. Also protected the withdrawal by voluntarily remaining last on the ground beaten by enemy automatic weapons”.

This citation includes the Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with bronze star.

Then came the climb up the Rhône valley towards Dijon (September 1944), and the hard fighting in the Vosges in October 1944.

On November 1, 1943, he was appointed Master Corporal.

On November 20, 1944, he fought in Belfort, before the tough Alsace campaign, where he took command of his group following the death of his Sergeant-Chef, and led his men into battle, including Jebsheim (68), where on January 30, 1945, the battalion lost 32 men in a single morning (including 6 officers) and a hundred more wounded (including 10 officers).

On February 1, the Bataillon de Choc had to relieve the Commando de France at Durrenentzen (68), which had suffered heavy losses the previous day in its attempt to take the village (53 dead and a very large number wounded).

The Battalion succeeded in taking the village at the cost of a further 10 dead and several wounded, including Raymond who was seriously wounded during the assault on an enemy barricade. He was evacuated to a military field hospital at the rear of the front (Saint Dié?).

He was commended in the Division Order and awarded the Silver Star Croix de Guerre.

He rejoined the Shock Battalion in Germany on May 2, 1945, just before crossing the Austrian border, where he ended the war on May 8, 45 with his comrades in Dalaas, celebrating the end of the fighting: immense joy at being alive, but also immense sadness for all the lost comrades who are no longer with us…

On July 1, 1945, he receives his Sergeant’s stripes.

The remnants of the 6 Shock Battalions of the 1st French Army form the 1st Regiment of Airborne Shock Infantry (1 R.I.C.A.P.) and return to France at the PALU camp in Bordeaux.

Sergeant LUQUET embarked in Marseille on November 2, 1945 and landed in Morocco on November 4. He returned home to the Moroccan capital, Rabat, on December 10, 1945.

He returned to service in Algeria a few years later.

He died on September 27, 2011 in Evian-les-Bains (74).

His decorations :

La Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 avec 3 étoiles,

La Médaille des blessés avec un étoile,

La médaille Commémorative 1939-1945 avec agrafes Italie France Allemagne,

La médaille Commémorative A.F.N avec agrafes Maroc et Algérie.

Henri Louis WAJNGLAS 1922 – 2003

Henri WAJNGLAS est né le 24 avril 1922 à Paris dans le 12ème Arrondissement.

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, he learned the trade of upholsterer-decorator.

On July 6, 1942, he was drafted into the “chantiers de jeunesse n°11” (youth work camps), where he remained until June 19, 1943.

He escaped from France to go directly to North Africa, crossing the Franco-Spanish border on July 14, 1943, the national holiday.

He was interned in Spanish jails the following day, and not released until November 16, 1943.

He landed in Casablanca on November 23, 1943, where he joined the Air personnel depot at base 209.

He joined the 1st RCP on February 18, 1944.

He took part in the Italian campaign from March 31 to September 4, 1944.

He obtained his parachute licence n°1944 on May 1, 1944 in Sicily.

On September 6, 1944, he touched down in France at Valence-Chabeuil in the Drôme region (26).

With the 1st company of the 1st RCP, he took part in the terrible campaigns in the Vosges (October 1944) and Alsace (December-February 1945).

He was demobilized and discharged from the army on August 16, 1945.

Returning to civilian life, he and his wife founded VAINGLAS (now VAINGLAS INTERNATIONAL) in 1960, specializing in upholstery and decoration.

He died on May 29, 2003 in Boissise-le-Roi (77) at the age of 81.

With this portrait, we pay tribute to him and his comrades-in-arms.