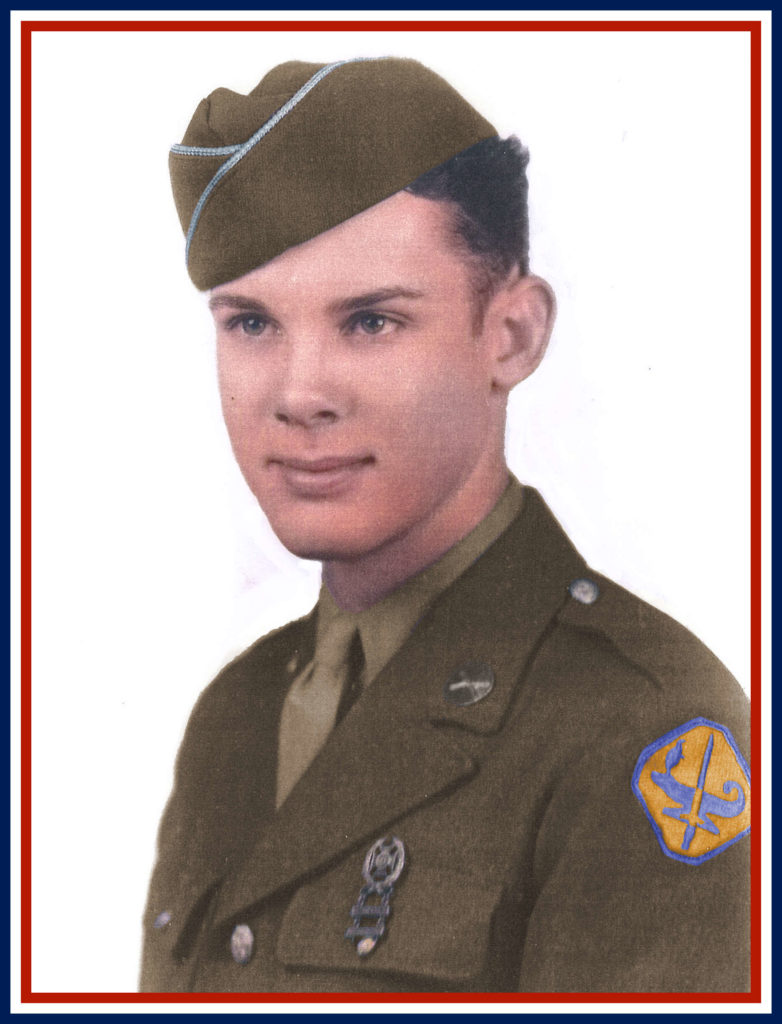

Bill George PRATER 1924 – 2019

I was born in Springfield, Missouri, October 5, 1924.

After attending Greenwood School from kindergarten through the ninth grade, I transferred to Springfield Senior High School, graduating in 1942.

On December 7, 1941, we were playing sandlot football in a field next to Clara-Thompson Hall at Drury College when we heard about the Japanese bombing Pearl Harbor.

That was a day no one can ever forget. After that horrible event, most of us decided to join the Armed Forces. We found an Army plan that allowed us to stay in school, finish college, and be better prepared for military duty. Therefore, with several high school friends I enrolled in Drury College, September 1942, and signed up for the Army School Program.

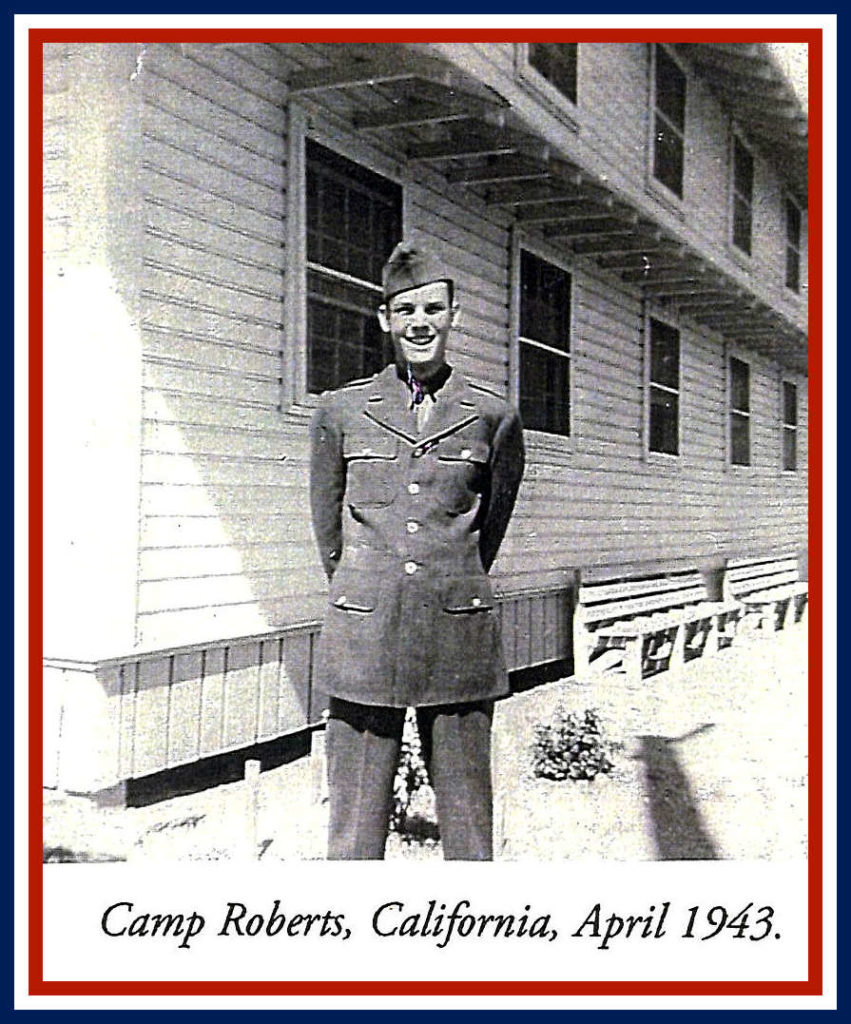

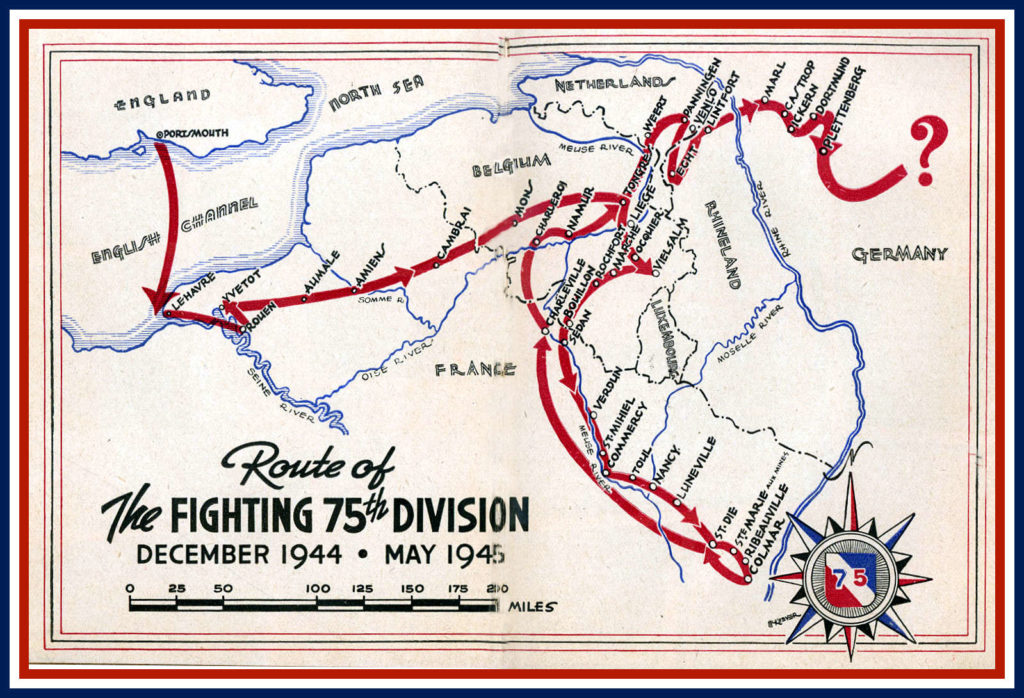

However, the war was not going well for the Allies in Europe nor the South Pacific and our plans changed. In the Spring of 1943, the enrollees in most of the military school programs were called into active service. Our group from Drury College was ordered to report to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis where we were inducted into the U.S. Army. Following training, I was assigned to the 75th Infantry Division, 291st Regiment, 2nd Battalion, “H” Company. While I was training at Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky I met Jim Strong and John Malarich. Our friendships lasted the rest of our lives.

At the end of our Breckinridge program, we were transferred by train to an embarkation port in New Jersey and boarded a Liberty Ship. We crossed the Atlantic arriving at Swansea, South Wales, and were transferred to Haverfordwest in Pembrookshire. An empty, downtown clothing store served as our barracks. There was no furniture, so we slept on the floor, which wasn’t too bad. The worst thing about this time was the food. I remember having over-cooked brussels sprouts twice a day. For years, I wouldn’t eat another one. I was promoted to Private First Class for my position as an assistant squad leader of a mortar squad.

In November 1944, we were taken from Wales, by truck, to Southampton, England where we boarded British landing craft to take us across the English Channel.

We landed on the north shore of France, where we were immediately taken by truck to the southeast near Rheims. We camped out in a field for a week or two, by then the field was ruined with our muddy boots. While stationed there, we would walk to the road and see the local French people and their children. One soldier in our company, who was not too bright, actually asked, “How did those little kids learn to speak French so well?” How do you answer that?

Here I was in France during World War II. It is interesting that my father (Matthew Cyrus Prater) was in France during World War I, serving as a sergeant in the Medical Corps. He was a pharmacist before being drafted.

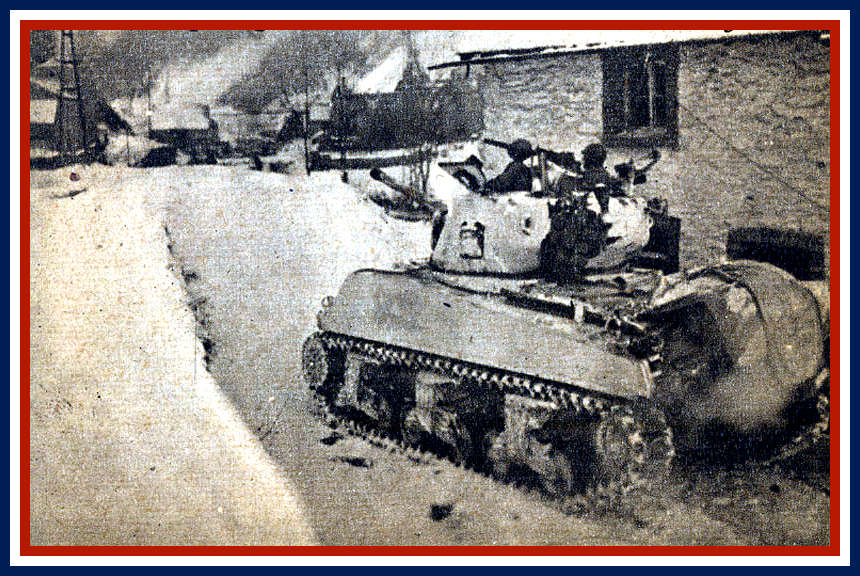

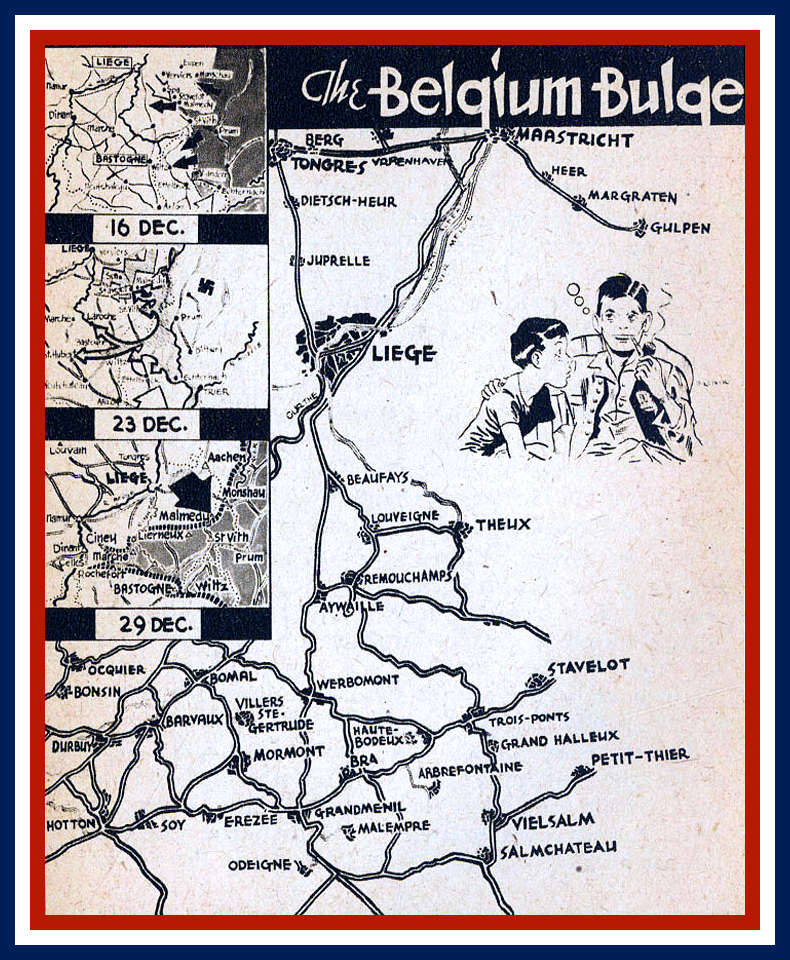

We moved by truck east into Belgium, through Liege, and toward the battle area. As the vehicles rolled across the Belgium countryside and through the small towns, the citizens wildly greeted us as American soldiers. They would come out waving Belgium flags, giving us postcards—giving us apples. I was riding in the back of a jeep, right in the middle of all this friendliness. We did not know we were about to save the Belgians from the Germans. The German Army had broken through the Allies line in eastern Belgium. The bulge they created was moving westward as we went through Belgium to begin our part in THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE!

BATTLE OF THE BULGE

About December 15th, 1944, we moved to a spot south of Liege, where we dumped our packs, picked up light gear and moved on into an area close to Tongres, Belgium. It was in this area we first heard the artillery shells and the heavy fire that was going on in the “Battle of the Bulge.” From there we moved into the tip of the Bulge, near the town of Marché. There we had our first encounter with German troops. We were on an outpost in the town when our squad was asked to take a forward position and watch for the enemy. Of course, we heard all kinds of noises, artillery fire in the distance, and voices that we thought were Germans behind us although we didn’t see any. One of the rifle companies behind us did and fired at a few of them. Shortly thereafter, one of the machine gunners in our company thought he was encountering a German infiltrator. Our first casualty was friendly fire that killed our company barber. We spent the night on patrol. It was one of the few times I did not take my shoes off. I learned afterwards to always take them off —no matter what—because my feet were almost frozen that night. I could hardly get my galoshes back on over my high-top Army Issue shoes. (We had not received boots.) After that experience I learned to take my shoes off, put them inside my sleeping bag to keep them warm, and put my galoshes under my head as a pillow. My left foot still bothers me in cold weather. During our short stay, we did not encounter any more combat in this area.

We were moved up north and back to the east where we fought in the “Battle of Ardennes.” Our participation in the “Battle of Ardennes” started about the 23rd of December 1944. On the 25th (we thought it was the 25th), we fired our first mortar rounds. These were smoke shells so that some wounded infantry ahead could be rescued. We named our mortar “Smokey Christmas” since we fired it for the first time on Christmas Day. This was the beginning of actual combat where we had our friends killed and wounded. Our troops were eager, but raw and inexperienced, so this was a tough start. The young men quickly became older and ‘combat wise.’

It was here on the edge of the Ardennes Forest that we met a muddy jeep with two soldiers, a captain and an NCO (non-commissioned officer) who were also covered with mud and very scared. They were escaping from the advancing German Army that had overrun the American 106th Division. This Division was totally surprised by the German attack and about two-thirds of them were captured.

The troops of all nations were under General Eisenhower, however General Montgomery had control of the British and American troops on the northern flank of this bulge that the Germans had pushed into Belgium. The plan was to drive south and east while the American Third Army under General Patton drove north toward Bastogne.

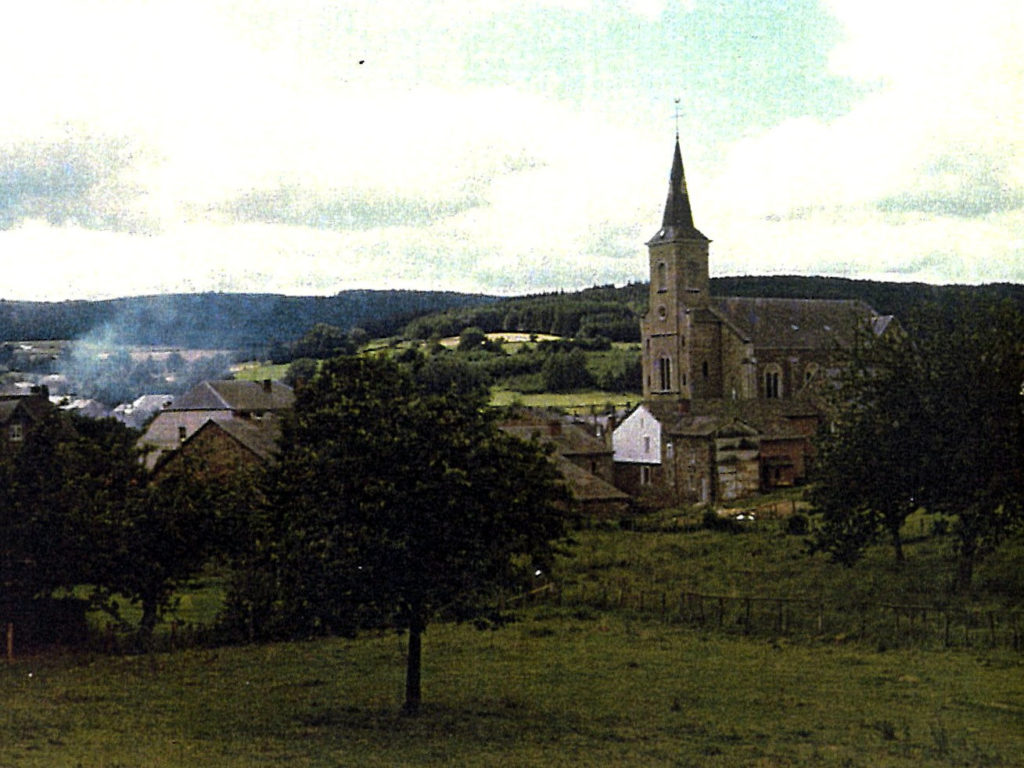

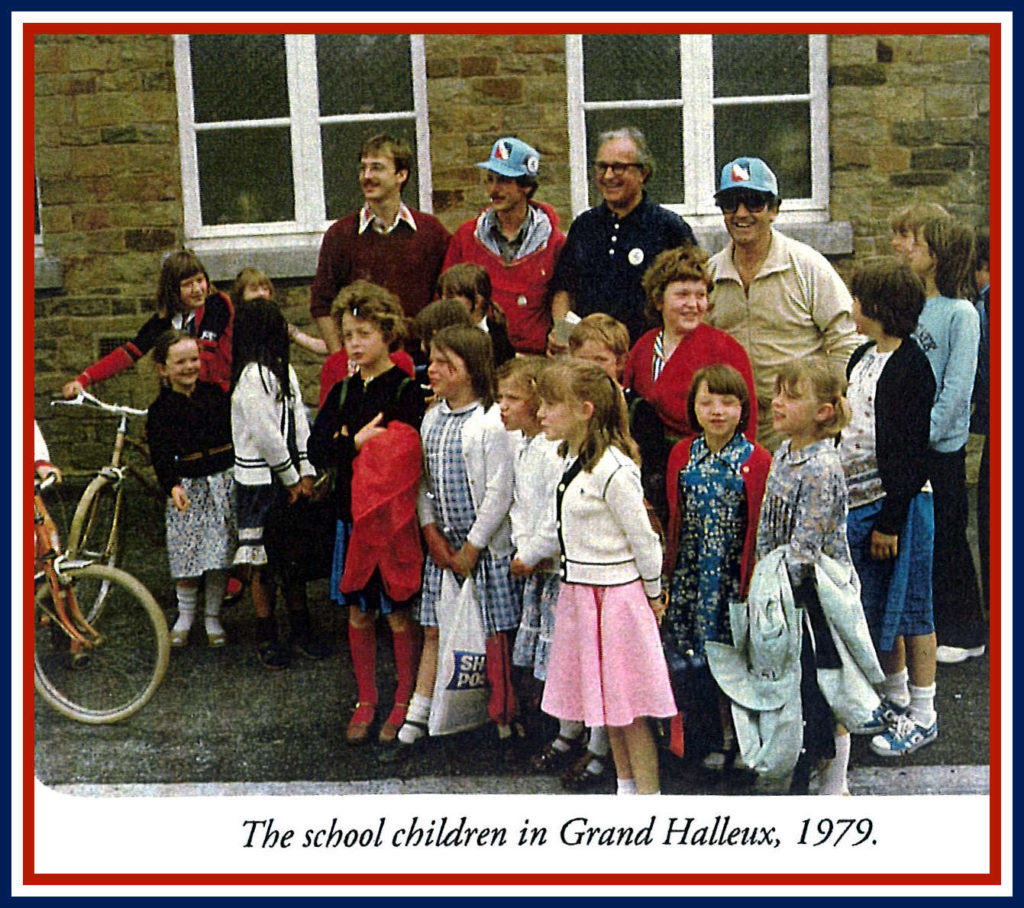

Our division got into active combat on the top (north) portion of the wedge of this German bulge. We went through some small towns, the names of which will always be remembered, Grand Halleux and Petit Halleux. This was the area where we were pinned down by the Germans who set up their equipment during the night while we were sleeping in village houses. When we came out of the houses the next morning, we faced machine gun fire from down the street and down the valley behind the house where we had set up our mortars.

Our first casualty in H Company was Charles Hartraff, who was married and had a child, one of the nicest guys in our company. There were more casualties during the day—in both the machine gunners and the infantry rifle troops. The Germans were on the ground above us, shooting down at us. We were in a terrible position. Fortunately, we had set our mortars on the valley side not at the bottom of the hill, or we would have lost more men. Our ammunition bearers were pinned down by machine gun fire and couldn’t get across the road to bring us supplies.

Our Company Headquarters was shelled. The Company Commander was wounded, killed was one of the lieutenants, our mortar platoon sergeant (Lee), and Sergeant John Bessmer (married only a few months earlier). We lost Lieutenant Leroy Wallis, who was the only officer assigned to our mortar platoon and Sergeants Finke and Stewart from the machine gunner platoon. Three or four other men were wounded in this heavy mortar attack. Our executive officer, Captain Goodnight, took charge. He was a much-liked person, a professional football player, drafted into the army like the rest of us. He was with us for quite a while, and we were fortunate to have him. He was not wounded, but had acute appendicitis, and we lost him after a month and never saw him again. Captain Goodnight was a good officer, and we missed him.

We advanced from Petit Thier, toward the village of Poteau, which was held by the Second Battalion of the 290th Infantry. We came in at night without meeting any resistance or seeing any action. We were awakened in the morning by artillery and mortar fire. I was sleeping on the ground floor of a little wooden shed behind the barn, when a shell hit. It set the shed on fire and one of the mortar gunners sleeping there was killed; Corporal Johnson and I slept in the same house the night before in Petit Thier. We moved into the shed in Poteau after dark. He was killed by the tank shell, and I wasn’t hurt.

We quickly moved out to take a defensive position and could tell the Germans had a tank set up as close as 100 yards away from us! We had one tank knocked out, but soon the German tank also got knocked out by artillery fire. We were firing our mortars at about 100 yards, which is as close as possible, but it was hard to tell how much damage we were doing. At least there was not a flank attack on us. The wounded were difficult to handle because we had only barns and a few houses to protect us. Fortunately, the stone walls were about a foot thick. Behind those stone walls, we were safe from small arms’ fire. We had to move several of our wounded into the building toward the back of the town so they would be protected. We had no physician and only the company aid men to support them. At that time, Colonel Jesse Drain was our battalion commander. He helped considerably in keeping the men together and keeping the defense parameter intact. I think he was awarded a Silver Star medal for his action in this area.

In the area south of Poteau, some Germans were captured. This helped reduce pressure upon us. That night we were relieved by the 517th Parachute Infantry of the 82nd Airborne Division. As we pulled out, there was still enemy fire. Two men from my section (I had control of two squads at this time) were running back toward the woods—Jim Strong and Floyd Ross. An artillery shell hit between them, bounced away without exploding, and they made it safely. I still correspond with them today. (Jim Strong died in December 1998). I walked out along the road with the rest of the squad. We all met up at the far edge of the woods, and then were able to move back from the town.

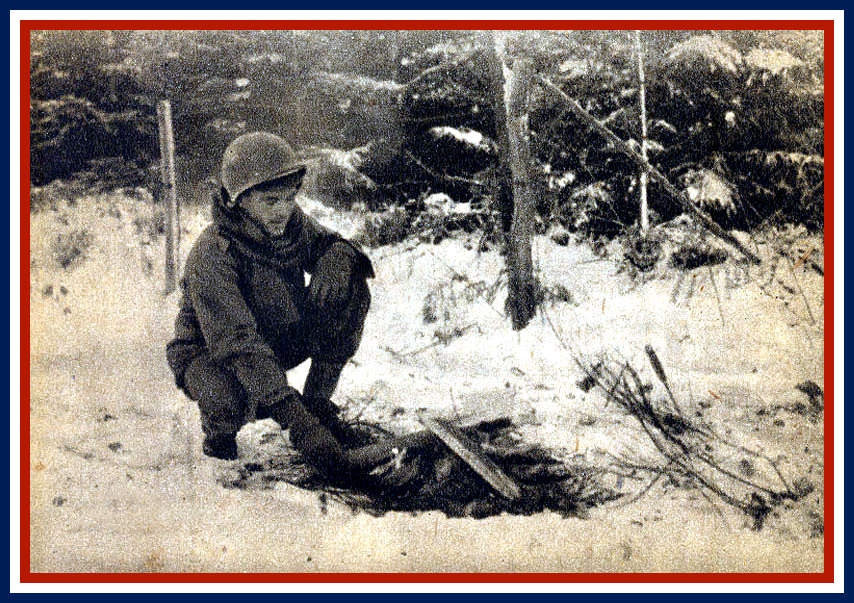

The next village we were ordered to capture was Vielsalm, but the Germans had withdrawn because our troops were putting pressure on both flanks of their position. However, they left mines and booby traps in the town. Fortunately, we were able to find most of them for the engineers to remove. We moved our division command post, as well as our division, through the woods during the night. This was between January 18 and 21, 1945. We moved farther south and east during that night. This was always an experience; to move at night on trails through the woods. This is where occasionally, we would have to sleep out, scraping the snow away, laying our raincoats down, and throwing our sleeping bags on top. We only took off our shoes but had them handy inside our sleeping bag. At these times, we would get extra food. The loss of personnel from frozen feet, wounds, and death gave those of us remaining, extra rations and extra equipment. One infantry man in our company broke a leg walking in the ruts and snow at night where you could not see.

Company G, an infantry company with whom we were closely associated, had heavy combat south of Poteau after we had moved toward Vielsalm. They faced tanks and German infantry but were able to repel them. Our company gave them some mortar support at that time.

Self-inflicted gunshot wounds during combat became a problem. In our company there were two instances of these injuries. One was shot in the foot, claiming he was knocking snow from the barrel of his M-I rifle. With his finger on the trigger? The other soldier said he was sitting with his back against a tree. He moved and shot himself in the leg when his pistol fired through his holster. These so-called ‘million dollar’ wounds sent both men to the rear. We never heard of them again.

It was interesting during combat that you could identify the small arms’ fire. The German machine guns, which we called “burp” guns, because they were hand-held automatic weapons with a very rapid rate of fire. The “burp” gun fired about twice as many rounds per minute as did our machine guns, so you could identify which side was firing.

Another big problem during The Bulge was the weather. It snowed almost all of the time and was so cloudy that our aircraft could not fly; therefore, we had no air support from England. Ordinarily, we would have expected the B-17s and B-27s flying over giving us protection, but it was impossible for them to get off the ground or to find us if they did. When the weather did break, here came the Air Force! This was the final blow to the German army as we were able to stop their advance and we could go into attack mode. I remember seeing the bombers come in fairly close formation on the first bright day. There were the big brown ones from England which had no fighter support because we were too far for fighter planes to reach.

However, the Germans did have fighter planes in our area. Occasionally, we would see small German fighters up and around the American bombers. The bombers would then spread out, so they were farther apart. We did see a few bombers shot down, but only a few. We saw the parachutes floating when the crew was forced to bail out. The presence of the Air Force was a great morale boost for us. Of course, it made our situation much better since the bombing could resume and we did have air superiority.

During the time of the snowstorms in Belgium, we frequently had to dig in. Usually, we could scrape enough snow away and chop a little of the frozen ground a little to get us a mini-foxhole. One afternoon in particular, we came along an open area on the edge of woods. We stopped and were to dig in before advancing the next morning. We heard tanks in the distance (we knew they were German tiger tanks) and we were pretty anxious to get dug in. We worked very hard and got nowhere. We could not get any ground broken at all, and soon found we were trying to dig on an abandoned air strip. We moved farther into the woods where we could dig in a safer position.

Foxholes, or ditches, were our protection and at night we could use our sleeping bags. When not moving forward, we could get some sleep by posting guards in pairs. Guard duty was nerve-racking because it appeared that every tree or bush would move. We would change positions, very carefully, hoping to see better. We had heard of German soldiers wearing American uniforms behind our lines. We didn’t encounter any infiltrators, but our wariness increased. We stayed close to the roads, not a cross road that could receive artillery fire, but where we could hear approaching vehicles. Tanks could be heard easily in spite of the artillery barrages. Sleeping was at a premium and after guard duty, we would bundle two or three guys together for warmth. We traded guards every two to three hours.

Keeping warm was a problem in the Belgium winter. I wore regular underwear, long wool G.I. underwear, wool shirt and pants, a wool sweater and a wool overcoat. Unfortunately, we had only cotton socks, high top shoes and galoshes. The wool stocking cap we wore under our helmet kept our heads warm, but our gloves were thin and usually wet. We had a raincoat which we put under our sleeping bags to keep us dry and we had double sleeping bags (because we took them from the casualties.) We had to cut up our blankets to make gloves. We also cut holes in blankets to make headbands to keep our ears from freezing.

We often heard German rockets going over our head. They had V-1 and V-2 rockets. One of them was kind of a putt-putt rocket that they were shooting toward Belgium and England. We would hear these go over, but we couldn’t hear their final explosion because they were well behind us. Also, we heard small German aircraft. They were artillery-spotting planes similar to our Piper Cubs. We called them “Bed-check Charlies” because they always came over late afternoon to spot where we were so they could be getting artillery ready for us. We could see one occasionally, but there was no anti-aircraft fire or any action against them. The Americans, of course, had the same situation. Our small planes were doing the same thing.

All of our troops had hand grenades and I put mine in my overcoat pocket. One day I stuck a cold hand in my pocket and felt the loose firing pin on my grenade. I gently pulled the grenade out while holding the firing handle. The pin was half out so I put it back in place then gave it to a machine gunner. He might need it and I certainly did not want it.

It was amazing how dirty we were, particularly our hands and faces. We were black from dirt, mortar shell powder, and smoke when we could build a fire. It seemed perpetual because we had no way to wash. Fortunately, it was so cold we did not perspire. We were always cold, tired, and scared. Usually, we were more fatigued than scared however, since at 18 years of age we were not smart enough to believe anything could happen to us. As the battles went on though, we became smarter.

It was toward the end of January, about the 21st, when we broke contact with combat and went back to an area for reorganization and rehabilitation. This was badly needed since our equipment was in bad shape and our personnel so badly depleted. On the 24th of January, while we were in R&R, Army Commander General Matthew Ridgeway replaced our division commander, General Faye B. Prickett with Major General Ray E. Porter. Prickett was not an aggressive officer and his inability to lead troops had proved he was not the type of division commander that was needed in such a crucial time. At the same time General Ridgeway replaced our division artillery commander.

THE BATTLE OF COLMAR

Our division was moved from the Belgium area once we had accomplished our mission and the final battles in Belgium were well underway. This time we moved by rail south into France, toward Colmar in Alsace. We traveled by rail in ‘40 and 8’s’, which was an experience in itself. We probably had 60 men in a railroad boxcar made for 40 men or 8 horses. There was nothing in the car, everyone had to sit on the floor, but there wasn’t room for everyone to sit at one time. You would stand up for a while, sit down for a while. You put your feet in the middle where the guy whose legs were on the bottom would have to pull his feet out every once in a while and put them back on top. The only way you could sleep was leaning against the side. With that many people, the humidity was so high, the water dripped from the ceiling. It was a couple of days before we arrived at our destination. The German army still held the district of Alsace, and we were called on to help the French First Army drive the last Germans out of France. The French First Army was commanded by General Delattre De Tassigny with the help of General Leclerc.

THE BATTLE OF COLMAR, called the ‘Colmar Pocket’, was another major campaign. There we were awarded our second battle star. The 2nd Battalion of the 291st infantry was setting up in the Colmar woods to allow the infantry to push toward the Rhine River. We fired mortars continually in an anti-personnel pattern. We would fire nine rounds covering an area about 200 yards square. This was probably our most effective mortar fire during the entire campaign. We were able to soften the German lines so our troops could move forward. There were a few roads through the forest, and we were stationed with our mortars at one corner of a road. A lieutenant, who was an engineer, and a couple of enlisted men, walked by with maps to decide where we should move next. About ten minutes later, the enlisted men came back. The lieutenant had tripped a booby trap and was killed.

During this campaign the kitchen was frequently able to get up to the front. They would come up after dark, and we would gorge ourselves, often get sick in the night, then have to get out of our sleeping bag. We knew we had to eat when we had the chance. Occasionally, we would also get breakfast before daylight, then they would leave us rations for the day. The kitchen tried hard, and they took chances getting to us. Usually, it was after dark when we got our only meal of the day.

On cloudy nights, anti-aircraft spot lights were often used for ground light. It was eerie seeing this light reflected from the clouds, but it did enable us to move around to change positions and set up mortars.

While we were in the Colmar area, we received our winter gear. Of course, the snow was gone, the weather was warming up, and the ground was mushy and soft. We received snow-pack boots, which are rubber on the bottom with leather tops, and new wind-breaker jackets, wind-proof pants, and wool socks instead of the thin socks and high-top shoes we had in the Bulge. We also got warm, woolen gloves with a wind-breaker type second glove you put over them. These would have been wonderful in the snow and cold during the “Battle of the Bulge.” Now we had good equipment and were envious of the Quartermaster Corps that had this equipment all the time.

We had fairly heavy casualties in the “Colmar Pocket” amongst the machine gunners and some of the mortar platoon as well. We were under artillery fire that was pretty devastating. Artillery fire is one of the worst fears you can have outside of being bombed. Two machine gunners up the road from us were together in a foxhole with a machine gun. A shell hit close enough to them that one was killed while the other man was not. However, the other fellow never recovered. He had a terrible shock and was taken back as a shell-shock victim.

During this time we received replacements. My section of the mortars, which consisted of two squads of eight men in each, was down to a total of six men. With the replacements, we filled up to about ten so we could handle both mortars but did not have enough ammunition bearers to keep us supplied. Our company suffered about 50% casualties, including battle and non-battle. We did manage to keep our jeep and our quarter-ton trailer. I had been promoted to Staff Sergeant, commanding two mortar (81mm) squads, but I wore no stripes. Our replacements were well trained, fresh and eager. They added a boost to our morale.

The French First Army was interesting in that they were typical Frenchman. They were terribly independent and seemingly fearless. One day their tanks went out in advance of us and the first tank got knocked out on the road. Here came another tank and it also was knocked out. Instead of separating their tanks and going across the field they sent a third tank out and it got knocked out. So, they were taught a different way than the American G.I. However, they prevailed, took another road out and were successful in the end. We then followed after them.

We were bombed while we were in the Colmar area. Only a few bombs were dropped but this was much worse than being in artillery fire because the bombs were so loud and so destructive. One time during the shelling we thought they were getting close to our headquarters house so we decided to evacuate. Running across the open door, I fell flat on the floor thinking I had been hit in the back, but fortunately not so. A small piece of shrapnel tore a little hole in my jacket and no damage was done. There were no civilians at all in the villages and areas we went into in Colmar. They had been evacuated long before and were safe from the Germans and the devastation.

While in the Alsace area, we were put back in reserve in the fortified town of Neuf-Brisach. We were able to look around the town, which was interesting in that it had a medieval-type stone wall all the way around the town. These walls were laid out in a star shape. Fortunately, we were in reserve and our part of the combat was over, while the other regiment of our division drove out to the Rhine River. On February 7, the “Colmar Pocket” was over and the last of the Germans were driven out of France. For this battle, our division received an award from the French called ‘Rhin et Danube.’ This consisted of a small patch and medal that we could wear on our uniforms.

It is amazing that during combat we rarely saw the people in headquarters platoon. I can’t remember seeing the Company H Commander or the First Sergeant during the battles. I know that our First Sergeant was wounded when a shell hit the hood of his jeep. The driver was not hurt. We had no, or occasionally one, officer in our platoon when we should have had four. Leadership was mostly NCO‘s (non-commissioned officers), and the overall plans were made by officers who were much higher up.

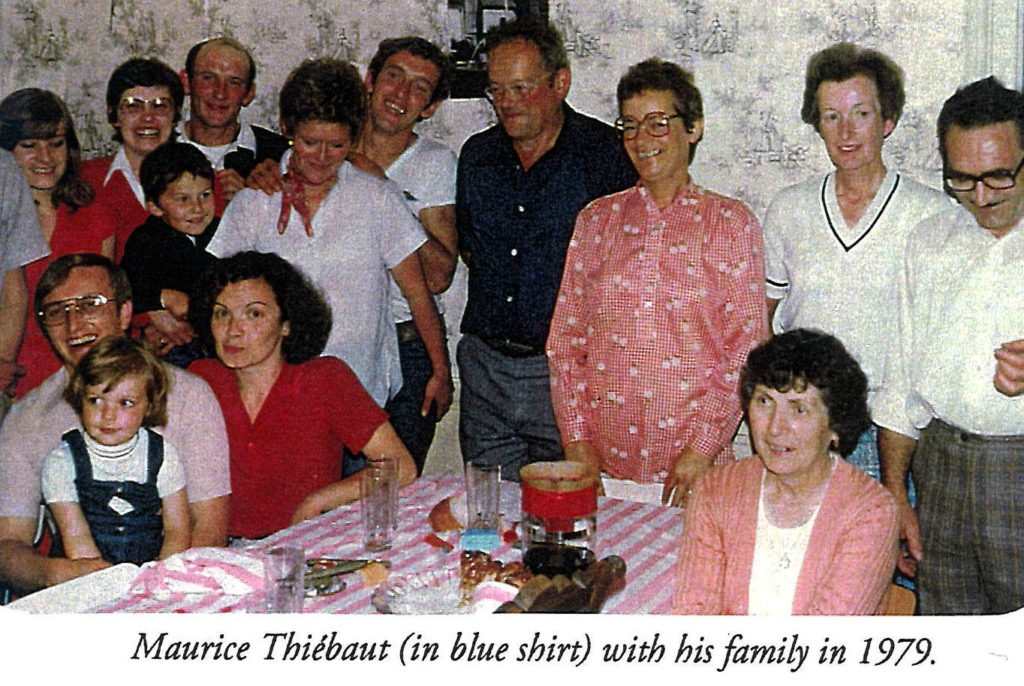

Our participation in the “Colmar Pocket” ended on February 9, 1945. We were transferred back behind the lines into the Vosges Mountains for “Rest and Recreation.” We were billeted in a small farming village called Rambéville, near St. Dié. Our platoon slept in a barn where we were supposed to rest, clean our weapons, get our gear in order, and be prepared for our next adventure. During our stay, we walked through the village of fewer than 500 people. We came up to a farm house where we spoke to the people in the yard and they invited us inside. Three of us went in to meet the family. Jim Strong could speak enough French to introduce us, and that is how we got acquainted with the Thiébaut family. There was the father, mother, and two daughters. They told us they had sent their son, Maurice, to southern France so he would not be conscripted by the Germans. I had a ‘D’ chocolate bar in my pocket. With my ‘D’ bar and their milk, I made some chocolate milk for all of us. We sat around the kitchen table and tried to visit, speaking only French. We also tried to play cards with the daughters. We visited the farm house often and soon Jim Strong was interested in getting better acquainted with one of the daughters. This R & R was a pleasant time far different from the rest of the time I spent in Europe during the war.

This is the Thiébaut Family that we have visited in post-war times. We had a very nice dinner at their home when our platoon visited them in 1979. Maurice came to the Dordogne area when our family rented a house there in 1985. My wife, Marie, and I visited them again in 1989 when we were in the Vosges. We continued to correspond at Christmas with Maurice. Maurice ran a dairy farm and at one time he also raised flocks of geese for the foie gras. In 1997, Madame Thiébaut wrote that Maurice had died during the year.

BATTLE FOR THE RUHR

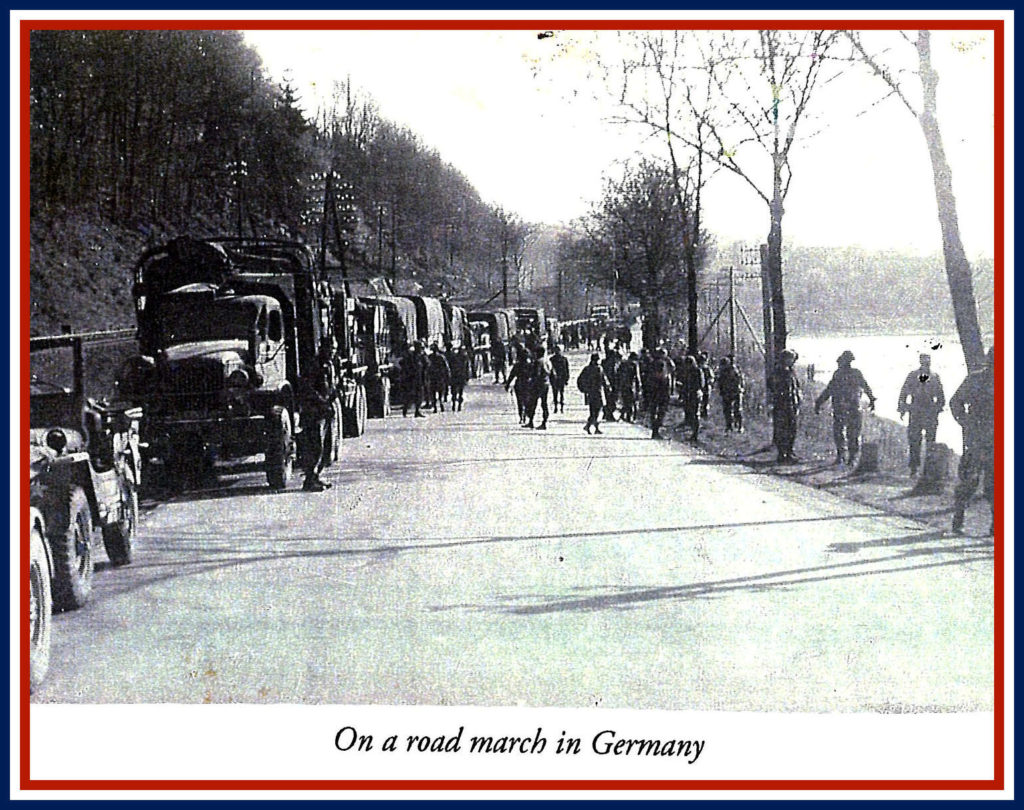

Our third battle star was for the BATTLE FOR THE RUHR. The Ruhr is an industrial area of northwestern Germany along the Ruhr River that includes the industrial cities of Essen and Dortmund. On March 9th our division was moved to the Rhine River well north of Essen, closer to the German city of Dorsten. We sat on the Rhine River for one or two weeks in a defensive area, preparing for the “Crossing of the Rhine.” We carried out occasional mortar fire while sitting on the river since German fortifications were just across the river. Our rifle company sent out patrols, but only along the river margin to protect us from German patrols trying to cross. No German patrols got across the river without severe losses. Our mortar section was in a nice home about 200 yards from the river itself. We had our mortars dug into the front yard. The first night we were there, John Malarich and I went to sleep on a soft feather bed. Of course, we slept in our clothes and I slept wonderfully well. I woke the next morning to find that John had gotten out of bed and slept on the floor because he said he just couldn’t stand that soft bed after sleeping on the ground during the rough winter.

During our stay there I was observing mortar fire from a barn down by the Rhine. I climbed up a ladder to the top of the barn and knocked out a shingle so I could see across the river. We had our mortars lined up on about ten different targets so that I could call for target by number and they would automatically set the site on the stake that aimed the mortars at that area. We had captured or found a German binocular periscope that we set up in this opening to observe across the Rhine. I could see the Germans but they were behind their fortifications at the edge of the river. I could see them walking in a courtyard and would call down the ID number of this target. If any troops appeared in the courtyard, I would call for mortar fire. The guys were good with their firing, but I really couldn’t see if I was creating anything more than a disturbance, which at least kept most of them inside their fortifications. One day while I was observing and my crew was shooting a few mortar shells at them, I was watching an artillery piece that was set up by the side of this barn. This was about a 105-millimeter gun that was firing on a low trajectory, more like a rifle, and I could actually see the shell come out of the muzzle of the gun because of my location. I couldn’t see where it ended but I could see it fly out of the piece when fired. Then, while watching for troop movements on the other side of the river, I noticed a shell from the German side hitting just below the barn. A few minutes later, I heard one explode behind the barn. That was enough! I was down the ladder, my radio man was there waiting for me and I said, “Let’s get out of here.” Sure enough, the next shell hit the barn. They didn’t hit the roof where I had been, but they did hit the side of the barn. I don’t know what else happened because by then we were gone.

We were there for a week to ten days while preparations were being made for the Rhine crossing. There was a bridge over the Rhine not too far from us. At night, the Germans would try to bomb this bridge. The artillery fire around the bridge was fantastic. It looked like all the fireworks in the world you could think of. Any time an enemy aircraft would come close, the firing would commence and there would be tracer bullets flying everywhere in the air, both from 50-caliber machine guns and from anti-aircraft guns. I did not see a plane hit, but we saw plenty of them change altitude or direction to get away from that fire power.

The morning of the crossing, we started our mortar fire about 5 a.m. We fired from 5 a.m. to daylight. We had never fired so many rounds of ammunition during the entire time we were there as we did that one morning. The barrel of the mortars is about 40 pounds in weight, approximately four-feet long, and 81-mm. in diameter. It was a heavy piece of equipment and fired a fairly good-sized shell. With that many rounds fired it created enough heat that you could not touch the mortar barrel with your finger. It was really hot and almost glowing. We got a little nervous about dropping the shell in and having it explode before it would hit the firing pin because of that heat. We kept firing at targets that were spotted on our maps, so we had the direction and range we needed. Evidently, we accomplished our goal, as I will indicate later. The next morning, the crossing was made without difficulty, both on the bridge and on pontoon boats. We crossed the following day on a pontoon bridge, which was built to carry vehicles no larger than jeeps and small troop carriers. When we reached the other side, we could see the German entrenchment, well built and deeply dug to keep their men safe. When the rifle companies crossed the river, the German troops had all pulled out. Our bombardments obviously were successful because of the amount of fire power in such a small area, all of the artillery behind us, and our aircraft bombing past the river. It really was a tremendous effort to clear the river for our crossing, and it was quite successful.

Our division was now in the Ninth Army under General Simpson. General Montgomery was the Army Group Commander over English, Canadian and American troops. On the second day after crossing, our battalion captured a large rubber plant of some kind, north of a town named Huls. This was later taken over as Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force. I don’t remember much about the plant, except it looked like it hadn’t been used for a while. There was only rusted machinery and no evidence of recent occupation.

It was during this advance through the German countryside that freed a small slave labor camp. They were older people, of several nationalities, none of whom we could talk to. When we opened the gates, they came flooding out. We indicated they could go anywhere they wanted to, go into any house and take whatever they could find to eat or wear. They were gone in no time, and that’s the last we saw of

them.

While we were advancing in the Ruhr area, our outfit and a rifle company that was with us started digging in for the night in an open field. We were able to observe some of the American planes coming over from their bases in France. There was a P-47 that came by on its bomb run, which was probably 500 yards in front of us. He made his turn, dropped his bombs, came back over us, and just as we were watching him, another bomb released. We were amazed as we watched this bomb come down. We took cover just before it exploded about one hundred yards away. Fortunately, no one was hurt. One other time we were strafed by British Spitfires. They saw us around some buildings near the woods. I suppose they were not able to identify us because two of them came down to machine gun us. We were fortunate when no one was hurt during the first pass, so we ran out to place our streamers indicating that we were Allied Troops. The next time they came down, they did not fire and left.

During our experiences in this area, we saw the first of the German jet fighters. We only saw them high in the air. They did not have many fighters and were not able to really do us any harm. Germany, at that time, was running out of fuel. They were not able to fly as much as they would have liked. We also saw horse-drawn ambulances that had been destroyed by artillery fire. The Germans used their horse-drawn ambulances to carry ammunition. Unfortunately, as we saw dead German soldiers, we also saw dead horses.

Many POWs (Prisoners of War) were captured in Germany. We saw them marching back through us, escorted by a couple of G.I. riflemen. They were both old and young. We were amazed at their ages. Some of them looked like they were hardly out of high school and some were really too old to be in combat. The Germans were using every man they could find.

The resistance was fairly strong through the Dortmund Canal area. Our goal was one of the canals that crisscrossed through this industrial region. We had obstacles to cross and German resistance along the way. When we moved up to the front into attack, many of us, me included, would often get nausea and some diarrhea. This would last one or two hours then disappear. I knew one man in our platoon that always got sick and finally was sent to the rear. He never returned. One of our riflemen had his canteen shot so the water poured on him, and he thought for a minute he had been hit. Another man told the story of having the tip of his shovel that he carried on his belt shot off. I can recall being in a bomb crater with John Malarich, our gunner, hearing a shell explode, hearing the shrapnel whistle, then pop—one hit him right on the leg. He grabbed his leg and said, “I’ve been hit in the leg.” We looked down at his leg, but it was all right. We looked over in the bomb crater and there was a piece of shrapnel about 3 x 2 x 1-inches smoking, lying in the dirt. The flat side had hit John on the leg and did not even break the skin. It bruised a little bit, but he was so lucky; for he could have lost his leg due to the jagged edges of the steel.

As we moved on through Germany after the infantry had cleaned out some of the resistance, we even hopped rides on the tanks since we were moving fairly rapidly. In some spots, we rode the tanks into small villages the German soldiers had just left, and the civilians were still there. I remember walking into a village bar where three or four of us lined up. The bartender poured us a beer, while some Germans sat on the other side of the room, nervously trying to pay very little attention to us. I also remember storming a house, not knowing who was there, and some old German folks came out with their arms up in the air, saying, “Nich Nazi, nich Nazi.” We confiscated a few chickens and rabbits along the way that we would cook in our helmets. We had boiled rabbit and boiled chicken, but it was hardly a worthwhile meal.

As we approached the canals, my duty was as a forward observer. I would go up with the rifle company as we approached the canals. I remembered helping a couple of injured guys coming out of a ditch. They were not seriously wounded and recovered in the rear area. Another time, my radio man and I went into a field bunker that evidently had been a food storage cellar. Two young German soldiers held up their hands and came right out with us. So, we captured two Germans without even trying! Another time, I climbed up along the edge of a small canal with the rifle company. We could look across the canal, which was probably 30–40 yards, and see the Germans moving back and forth, in their trenches. You could just barely see the tops of their helmets. Some of the riflemen would try to shoot one every once in a while, but they did not have much luck. Pretty soon, the German soldiers left. While we were there, I would often call for mortar fire, usually just smoke, to cover our men removing the wounded. Sometimes we would be able to give them good cover, other times they would be out of our range. Our platoon leader, in the rear, would try to add extra power to the mortars to get shells up there, but we did not always succeed. There was considerable German sniper fire from the buildings close to the canals. While I was with G company, a lieutenant climbing on a fence was killed by sniper fire. I think the sniper was caught shortly afterwards.

The Rhine River bombardment was around March 31. The “Battle for the Ruhr” ended approximately April 13th or 14th. This completed our last major battle in Europe. It was here, after the Germans surrendered, that we ran on to a couple of Russian soldiers on one of the canal bridges. We only spoke briefly since the only thing we could say was “Comrade.”

POST COMBAT

After the Ruhr campaign we were transferred to a small town in Westphalia, Germany where we served as Occupation Troops. We lived in a school house and were in charge of a DP (Displaced Persons) Camp. These were Russians, Poles and other Slavic peoples, both men and women. Our company shot a few deer in the surrounding woods. We took them to the DP Camp for the cooks to prepare for the inhabitants. They would usually prepare the tenderloins for us, which we greatly appreciated.

The War in Europe ended on May 8, 1945. We were pulled back to France. Troops were being assigned to return to the U.S., where they would be re-outfitted and transferred to the South Pacific. I was fortunate, for our division was sent to Camp New York in France for reassignment. I was assigned to the Signal Corps to process troops going to the South Pacific. The war with Japan ended in August of 1945, and again I was lucky. I was offered a chance to stay in France and go to school. I ended up in Paris studying ‘French Language and Civilization’ at the Sorbonne. This was definitely my best post while in Europe.

After several months, my number came up for transfer back to the States. I was offered a place in Officers Candidate School but going home sounded much better. The trip back to St. Louis was quick and uneventful. I was discharged (no reserve for me) at Jefferson Barracks in south St. Louis.

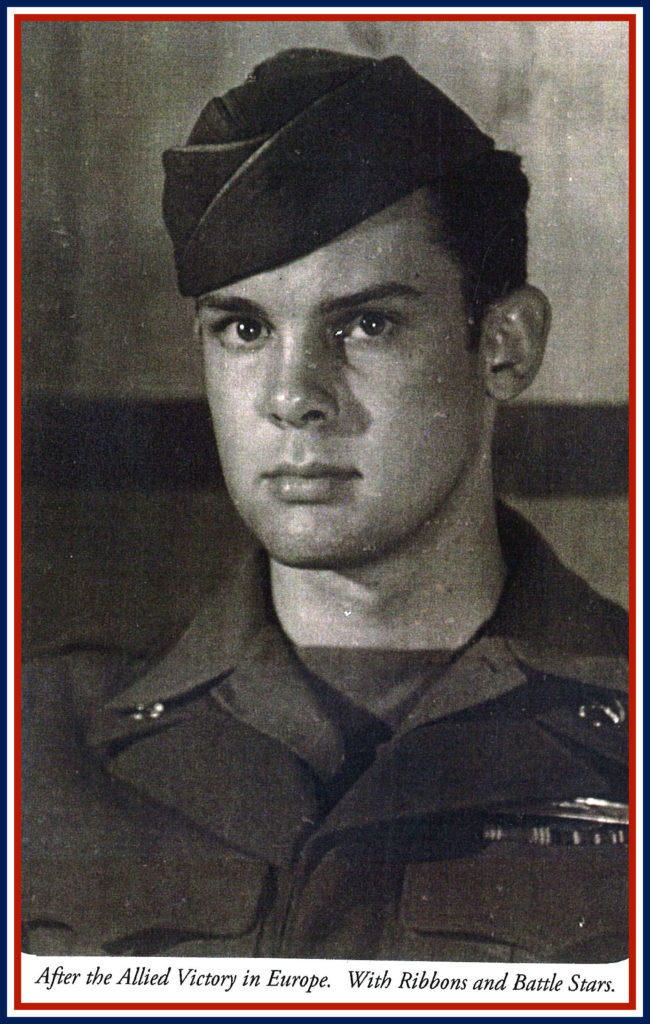

We were given a duffel with Army clothes, and I received my awards; “Combat Infantry Badge,” “American Theater Ribbon,” “European Theater Ribbon” with three “Battle Stars,” the “Bronze Star Medal” for performance in combat and the “Victory Medal.” Our division received the “Rhin et Danube Medal” and a “Liberation of France Medal.” In April 1947, the second battalion, including Company H, of the 291st Infantry received the Belgian “Croix de Guerre” by a decree of Charles, Prince of Belgium. This honor came as a result of our action in Belgium, during “The Battle of the Bulge.”

I immediately came home to Springfield.

I enrolled in Drury College again in January 1946. After completing that semester, I transferred to Washington University in St. Louis to finish my under-grad schooling. I was accepted into Washington University Medical School in the fall of 1947, graduating with a “Doctor of Medicine” degree in 1951. My schooling at Drury College and Washington University was covered by the “G.I. Bill.” These funds from a grateful country made those five and one-half years of education possible.

Following my Ophthalmology Residency, I returned to Springfield to practice medicine. In 1956 I did the first corneal transplant in Springfield and our office also did the first series of intra-ocular lens implants. In 1987 I volunteered for a month at the mission eye clinic in Sierra Leone on the West Africa coast.

Marie and I were married in May 1956 and had three children: Thomas George (b. 1957), Amy Marie (b. 1959), and Christopher William (b. 1960) and five wonderful grandchildren: Ford and Mac Wesner, Allie and Bryn Prater and Jackson Prater.

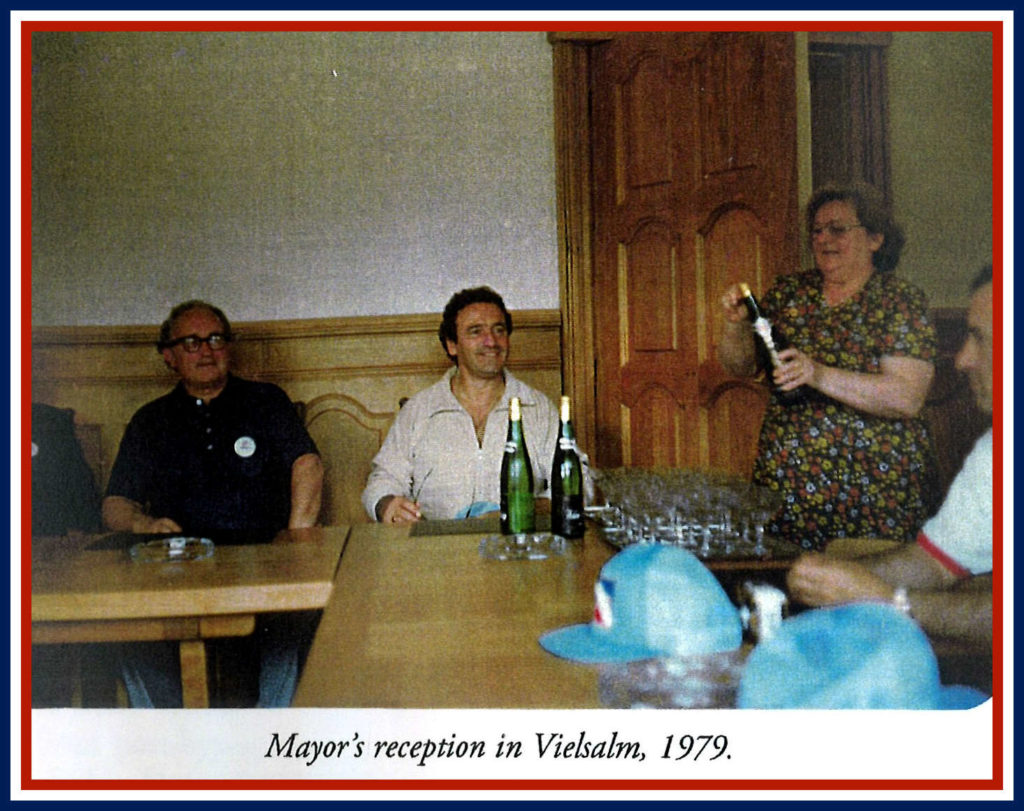

Marie and I have traveled back to France and Belgium several times, including a reunion trip to the battlefield areas with our platoon in 1979.

We visited Bastogne, Vielsalm and Grand Halleux, Belgium.

Then we traveled to the Vosges to visit the Thiébaut Family and tour the Colmar area.

Wherever we went, we were always met by the mayor at the Hotel de Ville and offered cookies and champagne, no matter how early in the morning we happened to visit. There were a number of very stirring moments, and the local French people made it a wonderful experience for us.

I enjoy golf, snow skiing, and skeet shooting. Our greatest pleasure has been traveling with our family. Since retirement at the age of 70, we have had five wonderful trips with our children and their spouses; rafting the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho, a cruise along the Inside Passage to Alaska, a barge trip through Holland during the Tulip Season, a trip to Peru and Chile, and a cruise up the west coast of Norway to above the Arctic Circle. We also enjoy spending time with our grandchildren and have skied with all of them in Aspen in the winters.

EPILOGUE

Dad passed away in 2019 at the age of 94.

He was a remarkable man and much loved by his family and friends.

He didn’t talk much about his time in Europe during World War II until the last few years of his life, but we always knew he came away from his time in the service with a love for France and the French people.

We are thankful that he put together his memoirs to share his experiences.

His son Chris Prater.

Thank you, Mr. Prater, for your commitment and for liberating our country with your comrades…we will never forget you!